Introductory French Neurasthenicism

Those proud few who have been here since day one will remember that the earliest (and now vanished) content on this blog was me liveblogging my way through Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, the second volume of which I finished last June. I’ve recently picked The Guermantes Way back up after a long hiatus. I’m at the part where Marcel is visiting Saint-Loup at the army barracks and the Dreyfussard politics are coming up. It’s interesting, if as always with Proust, slow going.

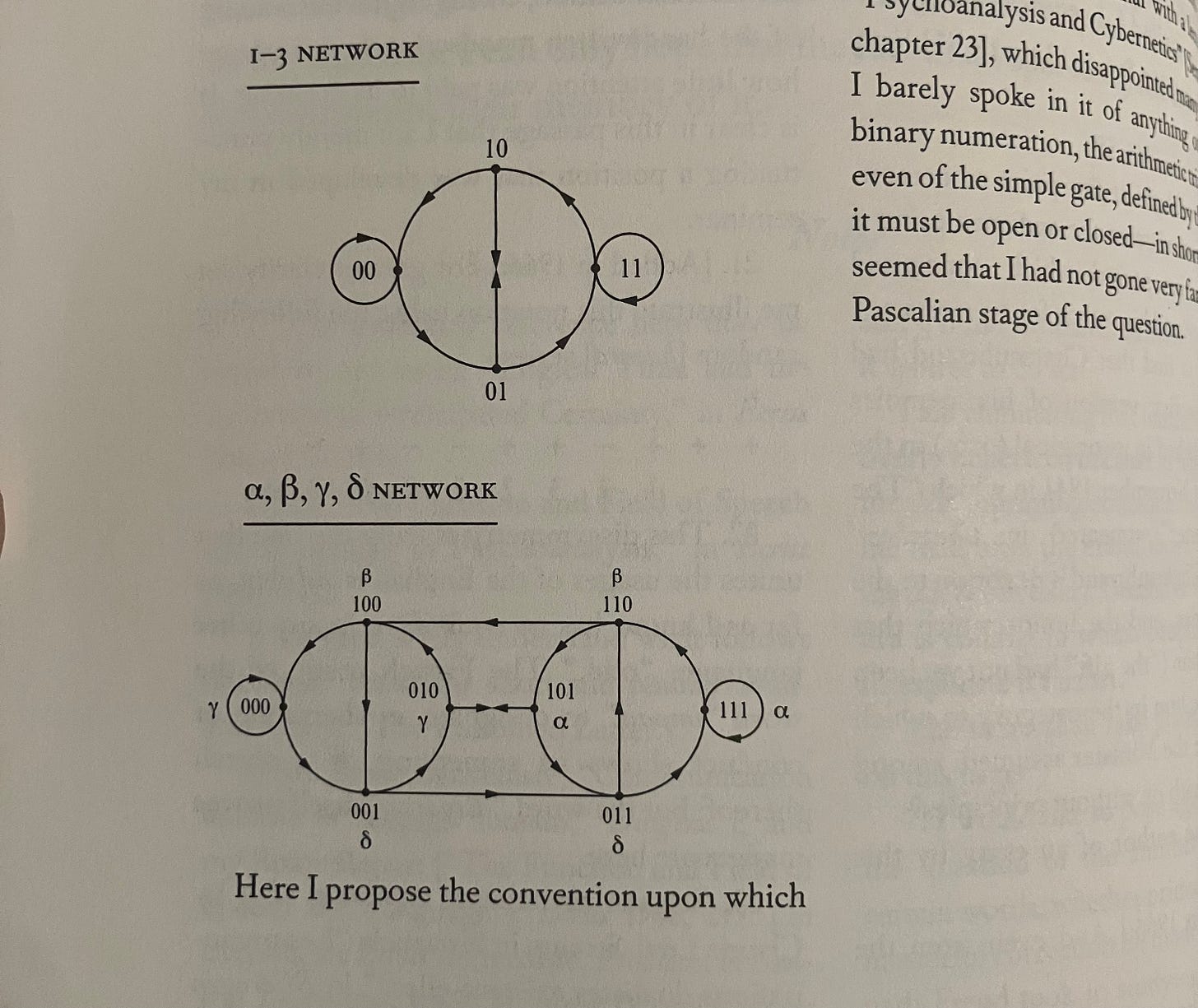

I’ve also been making a second and surprisingly much more fruitful attempt to read Lacan. I have been once more mysteriously ill, and so will allow for the possibility that my brainfog is making this most unreadable of twentieth century French thinkers make more sense to me than he otherwise would.1 I’m not sure how any of these doctines and ideas would work in an actual clinical setting, and Lacan sounds like a pretty awful therapist (he allegedly hit patients on more than one occasion), even more so than Freud, but it’s all very interesting!2 There’s something very seductive about his idea that the unconscious is language, to throw out one idea. The way he uses Hegel was also not at all apparent to me the first time I tried to read Lacan, perhaps because his reading is so dependent on Kojève’s.

Only psychoanalysis is capable of forcing us to recognize this primacy in our thinking, by demonstrating that the signifier does without any cogitation, even the least reflexive, in creating indubitable groupings in the significations that enslave the subject and, furthermore, in manifesting itself in him in this alienating intrusion through which the notion of "symptom" in analysis takes on an emergent meaning; the meaning of the signifier that connotes the subject's relation to the signifier.

I thus I will say that Freud's discovery is the truth that the truth never loses is rights, and that, although it may hide its claims even in the domain destined to the immediacy of instincts, its register alone allows us to conceptualize the inextinguishable duration of desire, a feature of the unconscious which is hardly the least paradoxical, even though Freud never gives it up.

A few very preliminary notes on Mark Fisher

I never read Mark Fisher while he was active on his now-legendary K-Punk blog, but the world I inhabited-to some extent still inhabit-online was one that existed in his shadow. He was the obvious model for so many of the bloggers I mentioned last time, critical theorists of Community or Doctor Who or other such things. His musical tastes have strangely structured my time online as well-less that I share them, and more that I keep being close to people who esteem his criticism. In any case I’ve been thinking about his work lately. Perhaps his chief manifesto, the slim 2009 text Capitalist Realism: is there no Alternative? is part of a small but notable canon that also includes Allan Bloom’s Closing of the American Mind- famous jeremiads that are when you read them really in a sense about pedagogy, about the instruction of the youth. A great deal of this text—especially Fisher’s famous passage about the headphones—is clearly coming from the perspective of a university lecturer.

Fisher was the great writer of what the introduction to the 2022 second edition calls the “hopeless entropy” of our century after the disasters of 9/11, the Iraq-Afghanistan wars and the global financial collapse shattered any lingering dream of a utopian end of history, leaving us with only a grim stasis, the “Capitalist Realism” of an endless present of exploitation and malaise. Much of this book still sings even if you don't necessarily share Fisher’s politics-the critiques of the endless managerialism, the monstrous growth of PR and marketing accompanying the denuding of actual substance from the late capitalist world and the like.

The power of capitalist realism derives in part from the way that capitalism subsumes and consumes all of previous history: one effect of its 'system of equivalence' which can assign all cultural objects, whether they are religious iconography, pornography, or Das Kapital, a monetary value. Walk around the British Museum, where you see objects torn from their lifeworlds and assembled as if on the deck of some Predator spacecraft, and you have a powerful image of this process at work. In the conversion of practices and rituals into merely aesthetic objects, the beliefs of previous cultures are objectively ironized, transformed into artifacts. Capitalist realism is therefore not a particular type of realism; it is more like realism in itself.

This was a pivotal text for many people my age and older, but I do wonder how much it would mean to younger readers. I suspect that Capitalist Realism might be a difficult book to metabolize if you don’t remember the oughts-I came of age in the later part of the zombie period Fisher sketches toward the end of the book, after the financial collapse but before the political chaos really started churning, and frankly that might even be cutting it a little close. A Goldsmiths alumn friend had explained this book to me once as largely the product of changes in education in the UK during the 1990s and 2000s, and it was interesting to see that the new introduction for the second edition was composed of almost exactly that needed context.

It is finally an optimistic book by its own logic, Fisher closing on a note of renewed possibility, welcoming any sort of breach, even writing about ecological crisis without the customary pessimism, as an opportunity for change. For the most part I would associate the politics of this book, and Fisher more generally with a very humane marxism, the kind I probably have the least reservations about, but I will confess I found parts of the closing section of the book, with its invocation of the “Marxist supernanny” and seemingly optimistic look forward to a kind of collectively managed austerity more menacing than I had expected. Then again I may just be a typical American: incorrigibly, perhaps even pathologically individualist, naively imagining that the glory days can go on forever.

The long, dark night of the end of history has to be grasped as an enormous opportunity. The very oppressive pervasiveness of capitalist realism means that even glimmers of alternative political and economic possibilities can have a disproportionately great effect. The tiniest event can tear a hole in the grey curtain of reaction which has marked the horizons of possibility under capitalist realism. From a situation in which nothing can happen, suddenly any thing is possible again.

One wonders if the last decade has borne out this optimism for the left? Certainly there is a more vital tradition of vernacular Marxism (in the United States at least, I can’t speak for the UK) than there was in 2009, but one wonders if this has translated into any direct action? On the intellectual front part of the left seems determined to prove Hannah Arendt’s infamous contention about Soviets and Fascists correct, while another, perhaps more visibly pursuing a kind of Neo-popular front strategy, would seem in some ways to validate Alvin Gouldner’s observation that the managerial new class (now increasingly proletarianized) and Marxist-Leninist vanguards resembled nothing so much as the other. Is this a good thing? Someone less agnostic about the claims of the Marxist left than I will have to answer that question.

Some musings and misgivings about Ulysses

If I have one abiding reservation about Ulysses, it might be that we have become too comfortable with it. To read an appraisal of the book by an eminent critic today one would imagine it a wholesome and welcoming text, nothing more difficult or challenging than Oliver Twist or perhaps on a higher register Middlemarch, a friendly companion of the well-adjusted student on an idyllic summer day. My objection is a halfhearted one-the critics have convinced me that at bottom Joyce’s purpose is more or less the same as Elliot’s-but it does abide.3 Joyce has after all bequeathed to us a forebodingly opaque text, surely the most difficult must-read novel in the canon.4 It is inevitable that every great experiment becomes yesterday’s received wisdom, that every great piece of radical art will wind up dusty and antiquated under museum-glass and picked apart and made acceptable by the words of the scholars. As Philo did to the Hebrew Bible, as Porphyry did to Homer, so too have we done to Joyce. It can therefore be productive to return to early readers of the text to recover something of the strangeness. Something to be said perhaps for Jung’s bewilderment, Woolf’s snobbery, or Erich Auerbach’s appraisal in Mimesis.

Still clearer and more systematic (and also, to be sure, much more enigmatic) are the symbolic references in James Joyce's Ulysses, in which the technique of a multiple reflection of consciousness and of multiple time strata would seem to be employed more radically than anywhere else. The book unmistakably aims at a symbolic synthesis of the theme "Everyman." All the great motifs of the cultural history of Europe are contained in it, although its point of departure is very specific individuals and a clearly established present (Dublin, June 16, 1904). On sensitive readers it can produce a very strong immediate impression. Really to understand it, however, is not an easy matter, for it makes severe demands on the reader's patience and learning by its dizzying whirl of motifs, wealth of words and concepts, perpetual playing upon their countless associations, and the ever rearoused but never satified doubt as to what order is ultimately hidden behind so much apparent arbitrariness.

For a long time my relationship with Joyce’s opus was more or less of the nature that Borges describes in his 1925 review of the book. The great Argentine, a reader of the text in its own time, admits what so many of us do not so readily-that he has not finished the book.

I confess that I have not cleared a path through all seven hundred pages, I confess to having examined only bits and pieces, and yet I know what it is, with that bold and legitimate certainty with which we assert our knowledge of a city, without ever having been rewarded with the intimacy of all the many streets it includes.

My impression during that time—in which I read both Manhattan Transfer and Berlin Alexanderplatz, two slightly later works deeply indebted to Joyce—was that it was a remarkable experiment, but perhaps not something you needed to read in full in order to get the flavor. Eventually of course I did-ironically it’s the only one of the behemoth modernist novels (In Search of Lost Time, The Man Without Qualities, U.S.A., Pilgrimage) I have finished, and I half-regret to inform you that it is indeed essential, a must-read, you really can’t understand the twentieth century novel without it, etc.

I recently reread Samuel Beckett’s The Unnameable, the closing entry of his trilogy, in some ways a stylistic companion to Ulysses, something like the opposite pole. I admire without entirely loving it. Beckett in general is often verging on being the kind of late-or-post- modern literature I do not love, the sort of hyper self-conscious musings on the difficulty of the labyrinth we all find ourselves in as readers and writers living after God, after Heidegger and Joyce have finished philosophy and the novel.5 This is a labyrinth we all find ourselves in: it may be more or less evaded in a few ways, you can join a church or dedicate yourself to a tradition, or find a way out artistically, but we do start here, and sometimes Beckett can come a little too near to merely pointing out that fact.

I can't go on, you must go on, I'll go on, you must say words, as long as there are any, until they find me, until they say me, strange pain, strange sin, you must go on, perhaps it's done already, perhaps they have said me already, perhaps they have carried me to the threshold of my story, before the door that opens on my story, that would surprise me, if it opens, it will be I, it will be the silence, where I am, I don't know, I'll never know, in the silence you don't know, you must go on, I can't go on, I'll go on.

Joyce and Beckett escape from my tastes in exactly the same, which is to say exactly the opposite way. Joyce becomes too much, the total cacophony of the universe as Dublin under paralysis one half day in June 1904, Beckett too little, a solitary voice speaking an unbroken monologue for two hundred pages, speech persisting after the character and narrative it served have vanished, telling us endlessly what it was and isn’t cannot have been. One gets the strong sense that there’s something slightly masturbatory about them both.6 The gripes one sometimes has about Kafka one sometimes has about Joyce and Beckett as well, although it should be said that the humor that elevates them (which I do sometimes find tiresome, ) is more present in him than is sometimes noted.

The general way one is advised to approach Lacan is, from what I gather, to read several secondary sources explicating his thought, the published seminars, and then finally the essays contained in the Écrits. Because I am a foolish person, I read several of the essays in the Écrits first and am only now approaching the seminars and secondary materials.

For a dissenting view of Lacan from a recurring character on the footnotes of this blog over the last few months, here’s Stanley Rosen offering an acerbic take of Lacan in his late-life recollections of studying with Alexandre Kojève.

I found Lacan pretentious, obscure, and dull, a per- ception that will perhaps outrage the readers of this memoir but which I must confess I have retained for thirty-five years. This is obviously not in- tended as an informed scholarly judgment ; every effort on my part to re- place initial impressions by careful study of the key texts has met with failure.

It’s always comforting to know that someone who seems to have been much smarter and better read than oneself has also struggled!

I think this is so, and yet-we are as

recently observed in some ways closer to the nineteenth century novel than we are to the literature of the twentieth.Not coincidentally, both the Elizabethan poets and the modernists were obsessed with antiquity. The Victorians, with their dark satanic mills and their rain, steam, and speed, seem fusty to us now while Donne and Shakespeare remain somehow immediate. Though it should be said that when the English language is tamed it can be better harnessed into service creating characters, landscapes, minutely realized societies, as in the Victorian novel. I suspect the 21st century, with our world-shaking new social technologies and our attitude of haughty disdain towards the unenlightened past, will come to be seen similarly to the 19th.

Is it so strange that we read it as if it were that?

I don’t love Ulysses the way he does, and my misgivings about it are not the same as his, but my current understanding of the deeper meaning of the text is nonetheless inflected by John Pistelli’s masterful six-week course on the novel during the Brit Lit segment of his Invisible College lecture series.

This is an oversimplification, a generalization, a turn of phrase of the sort I can’t quite prevent myself from making. Of course one does philosophy after Heidegger, of course one writes novels after Joyce, and yet it does seem that certain horizons are closed, certain experiments no longer able to be repeated.

The closing Penelope section is surely the best part of the book, perhaps of Joyce’s corpus overall. A truly virtuosic performance, Molly Bloom is one of the most strikingly realized, most alive characters in the English canon. I am sometimes so close to joining Merve Emre in unqualified praise, praise that does probably constitute a betrayal of something or other.

It is probably a betrayal of the feminist literary tradition to pronounce the final episode of “Ulysses,” “Penelope,” the best—the funniest, most touching, arousing, and truthful—representation of a woman anyone has written in English. But it is, and the eight long, unpunctuated, and outrageous sentences of Molly Bloom’s silent monologue make much of the feminist canon look like a sewing circle for virgins and prudes.

And yet there is some ambivalence. Ulysses is in many ways despite appearances not a lit bro text, not really a masculinist work at all, but I do sometimes think I detect in Molly’s lusty pronouncements—recognizable as they are, as true to life as they seem—the voice of the phallus as ventriloquist praising its own prowess, its own ability . It’s not quite fair to the character or to Ulysses, but I can’t shake the impression that somehow Joyce provided the original model that like a photocopy, diminishing in fidelity with every iteration, eventually produces the inert woman as receptacle for male desire who mars the work of many of the otherwise great 20th century male novelists who follow Joyce.

Haha yeah the New Yorker/Atlantic critical line on Ulysses (prevailing anti-elitism being what it is) is like "It's nothing really -- just a touching story about a marriage, about a guy going for a walk around Dublin -- really it's easy if you think about it!" I don't think they should build it up to be some impossible modernist talmud, it isn't that either, but come on now.

I definitely also have my share of complex feelings about it though. I do love it, it has some of my favorite sentences in the world, but more than any other modern masterpiece that relationship feels a bit... well "abusive" is much too strong a word but it does feel sort of like the violent imposition of another consciousness, one that makes you wade through teethgrinding boredom, bad puns, accumulation of detail, all those babytalk compound words. I can't look up at night without thinking of his heaventree of stars. But does he have the right to so thoroughly override my brain like that? With my favorite novels it feels like another consciousness has given me a great gift. Ulysses is sort of like being given a gift that is indeed great and life-changing, but in the form of a finicky and delicate tropical fish.

Appreciate all this, as usual, but especially the bit about James Joyce. I've read too many bits on him (and Proust, Sartre, Hegel, etc) where the commentator tries to insist that the reputation for difficulty is overblown. I know it's uncool to acknowledge your struggle with a text, but to pretend some books can be understood intuitively on a first go just feels dishonest.