Hi again.

I think I told you last year that I’d be trying to finish my novel in my period of inactivity, but actually what I’ve been doing mostly has been reading. I’ve often noted that thinking persons of my generation and social class read philosophy above all else. We don’t read (many) novels, we don’t listen to especially challenging music, we read continental philosophy and feel sad and guilty about the world and our place in it.1 I largely avoided it in part for this reason, but I’ve been guilty of this myself recently. For whatever reason for about the last month or so I’ve been giving myself a crash course on the thought of Leo Strauss.2

Strauss is as his reputation would indicate a slippery character, a twentieth-century scholastic who taught more by negation than by doctrine. So much has been written about him, sometimes in quite extravagant terms, that I’ve been meaning to investigate in detail for a while.3 That said I’m going to hold off on actually writing anything about my view of him in any detail for a while: I’m still working on a few of Strauss’s mature works and I want to be at least minimally sure of what I’m speaking of-at least textually. There seem to be three or four sets of politics available from the books and essays themselves, which doesn’t even begin to interrogate what may have been transmitted in speech-surely one as well read in the classics as he would have known that there are teachings that cannot be written, that Socrates never did, what Plato said in his crucial seventh letter (thought in a supremely ironic development of modernity to be itself spurious, an antique forgery):

For this reason no serious man will ever think of writing about serious realities for the general public so as to make them a prey to envy and perplexity. In a word, it is an inevitable conclusion from this that when anyone sees anywhere the written work of anyone, whether that of a lawgiver in his laws or whatever it may be in some other form, the subject treated cannot have been his most serious concern - that is, if he is himself a serious man. His most serious interests have their abode somewhere in the noblest region of the field of his activity.

If, however, he really was seriously concerned with these matters and put them in writing, then surely' not the gods, but mortals have utterly blasted his wits.'

Lit digest: Hanya Yanagihara, Gertrude Stein, Joan Didion etc

I’m addicted to starting incredibly long books (I’ve got about five going at once right now) and I unfortunately succumbed once again the day after Christmas, beginning Hanya Yanagihara’s 2015 epic of gay suffering A Little Life, which is now competing with Mason & Dixon for my attention. I’m not completely sure why I started it beside that I’m trying to scope up the competition (ish.) Also, although rarely that compelled by contrarianism I suppose it helps that the right sort of person apparently dislikes Yanagihara pretty strongly at the moment for “stolen valor” and “torture porn” or something of that nature.4 Maybe I was enticed by the drama! I like it so far, Yanagihara’s tendency to describe everything and everyone in detail is a welcome change from a lot of contemporary fiction. I’ll let you know what I think in the end.

I also read Gertrude Stein’s 1908 landmark work of early American modernism, Three Lives. As with a lot of American modernism it’s aged interestingly-I admire the performance but there’s too much of it. The form cloys and sickens even in the two shorter stories on account of being written in a voice, a choppy immigrant speech to say nothing of the almost-novella Melanchtha, written in Stein’s impression of late 19th century lower class African-American dialect. Toni Morrison was probably onto something when she accused Melanchtha of a kind of vicarious minstrelry, a putting on of black masks to indulge in white pleasures. I’m glad I read it and you should too-there’s a lot that comes out of this book, from Hemingway to a certain mode of (white) hipsterdom, but I also kinda hated it, was annoyed by it etc. My least favorite kind of American fiction, the sort of affected thing imagining itself terribly clever for being composed entirely of spoken voices and sentence fragments flows in some sense out of this, which is at least in my view a questionable legacy!

More consequentially I finished Joan Didion’s 1963 debut novel Run, River. I understand that later in her life she came to find its nostalgia for her childhood objectionable, part of a false image of an ideal pre-WWII California of ranchers and pioneer aristocrats she came to repudiate. This is understandable-I think the book aspires to be something like Thomas Mann’s Budenbrooks or Mishima’s Sea of Fertility tetrology: a tragedy of once-great ones brought low by some degeneration through the ages, some falling away from greatness into dissolution and madness-but I don’t really think it succeeds.

"You can try her again when we get home." Lily fitted the key into the ignition with meticulous care while she tried to work the parade, the rain, and Sarah into some reasonable sequence. "By then it'll be after midnight in Philadelphia. Maybe they'll be home then."

"Oh no," Martha said. "It's only five-thirty there now.

The man in the Rexall told me."

"It's almost eight-thirty here. You know it's later there."

"I'm sure I don't know why the man in the Rexall would have told me a deliberate lie."

"If he told you that he just didn't know. We know." Martha shrugged. "I don't know. I don't know what to believe."

Lily switched on the windshield wipers but did not start the engine.

"Anyway it's too late," Martha said. "If it's midnight there, as you insist it is, it's too late."

"Too late for what?"

Martha leaned against the window and took off her sun-glasses. Her eyes were closed, "I don't know," she said. "I didn't want to go home and I thought I might go there, but it's too late."

"I don't know what you're talking about."

"Sarah. I'm talking about my sister. I wanted to taik to Sarah. If you don't mind.”

Madness, degeneration and the like: the novel does bring that-it’s a disjointed chronicle of elopement, adultery, unhappiness and unravelling-particularly vividly in the Quentin Compson-esque self destruction of Martha. The issue is that Didion doesn’t particularly succeed in conveying any sense that these people, these families, this world was ever great. Something-maybe style, maybe nihilism or nostalgia-betrays her here, and the roughly contemporary nonfiction gets across what she probably meant far better

it did not seem unjust that the way to free land in California involved death and difficulty and dirt. In a diary kept during the winter of 1846, an emigrating twelve-year-old named Narcissa Cornwall noted coolly: "Father was busy reading and did not notice that the house was being filled with strange Indians until Mother spoke about it." Even lacking any clue as to what Mother said, one can scarcely fail to be impressed by the entire incident: the father reading, the Indians filing in, the mother choosing the words that would not alarm, the child duly recording the event and noting further that those particular Indians were not, "fortunately for us," hostile.

while the herculean shallowness of the prose, the Hemingway-inflected matter-of factness with which everything is delivered prevents the family myths the characters of her novel are invested in from ever seeming like anything more than edifying fictions, an imagined background for a disintegrating present. It's a finely-wrought piece of work, but too much of shadows playing on the wall and too little character for my liking.

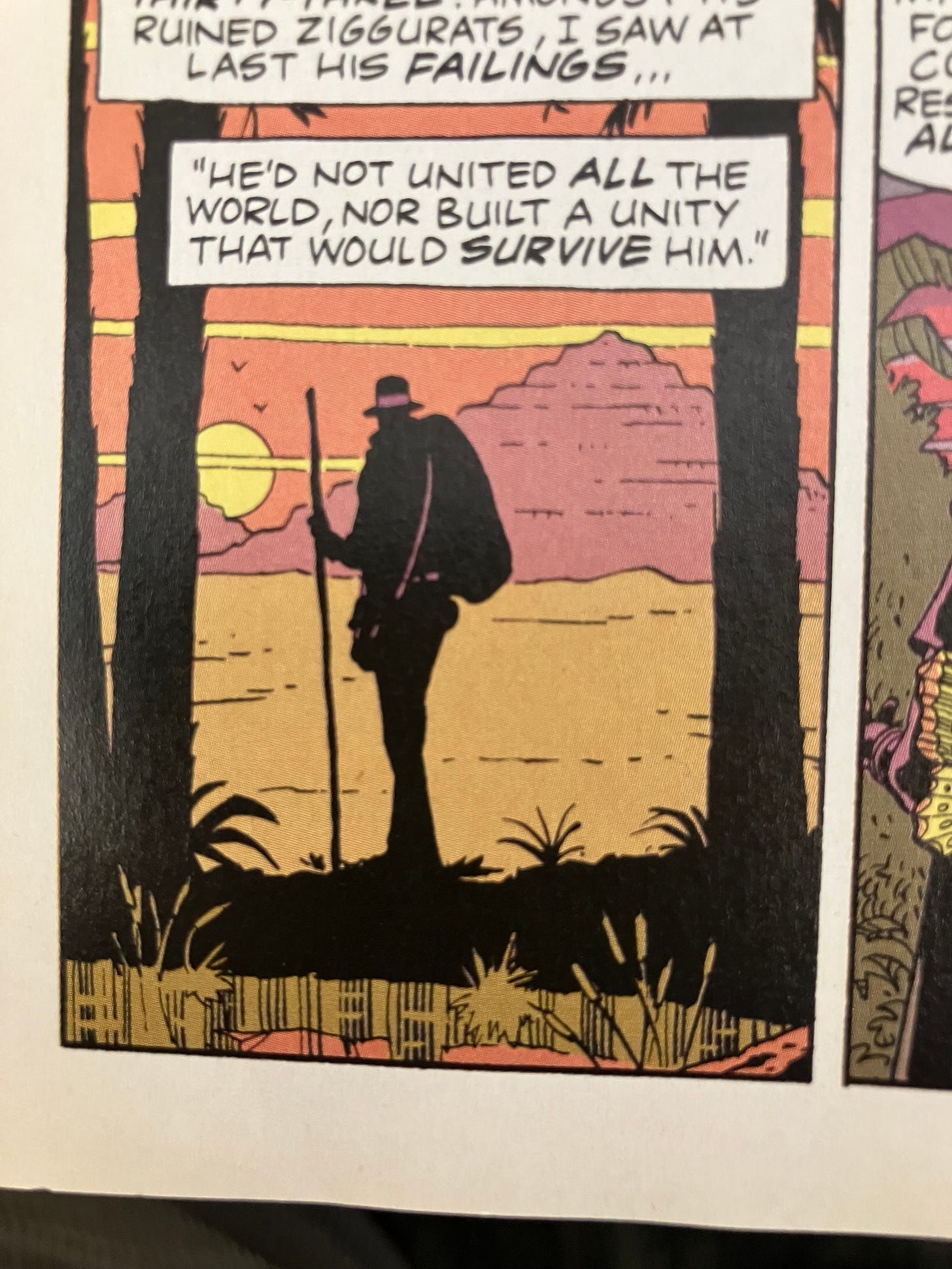

Some blathering about Watchmen

I reread Alan Moore’s Watchmen the other week so I could write something about its younger, edgier and looser sibling From Hell.5 Often considered the greatest superhero comic ever written, Moore plays with deconstruction, alternate history, and the more apocalyptic side of the genre in a way that I’ll generally avoid summarizing too much, because I think most of you have probably read the book already. In a way that seems strangely resonant with my reading of Strauss, Watchmen is largely about nihilism and the noble lies men of intellect and power tell in order to keep it at bay. The first time I read this I was mostly paying attention to all the superhero deconstruction, while now it’s the apocalypse talk in the second half that really holds my attention. It’s good! I don’t have any really earth-shattering discoveries to report, having revisited more out of a sense that I probably didn’t remember the story quite as well as I thought, andI didn't.

I’m not sure this is actually true, but this is how it often felt when I was attending the small New England university where I went to undergrad and the online spaces where I and my friends congregated in those years!

I think perhaps this flows naturally out of my interest in weird platonism.

There is a voluminous body of literature denouncing Strauss and the network of students and students of students that formed around him, often in terms of blame for the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the foreign policy misadventures of the second Bush administration more generally. I’ve also been reading one of the earliest and best regarded of these, Shadia Drury’s 1988 The Political Ideas of Leo Strauss. I’m not quite finished with it, but it’s a compelling thesis. Maybe a little neat and unified as an interpretation of a body of work-I’m not sure I agree with her that the east coast/west coast esoteric/natural right philosopher/gentleman schism within Strauss’s students is a feature and not a bug of his thought-but compelling nonetheless. I’ll keep you posted.

Readers who’ve followed me for a while will know that recurring subject of fascination and ire Andrea Long Chu won her pulitzer for an extended 2022 denunciation of Yanigahara

It is indeed a tourist’s imagination that would glance out from its hotel window onto the squalor below and conclude that death is the opposite of paradise, as if the locals did not live their little lives on the expansive middle ground between the two. But even Yanagihara’s novels are not death camps; they are hospice centers. A Little Life, like life itself, goes on and on. Hundreds of pages into the novel, Jude openly wonders why he is still alive, the beloved of a lonely god. For that is the meaning of suffering: to make love possible. Charles loves David; David loves Edward; David loves Charles; Charlie loves Edward; Jude loves Willem; Hanya loves Jude; misery loves company.

Not being either a literary-metropolitan sophisticate or a product of the English Department I’m never completely sure what’s going on behind the scenes with these critical smackdowns: are we looking at individual beef, institutional shots across the bow, or some other thing? Enlighten me below, o great ones!

A thought to be elaborated on later-Watchmen is all about control and From Hell is in some sense about losing it, as Gull does in the process of committing the ripper murders, and as the comic itself-and Moore as an author- seem to at points.

Regarding those critical smackdowns it seems like a good way to build a literary reputation is to be the one to start the preference cascade, the first one to say in public about a book what people already say behind closed doors. You don’t even have to be a great writer, just 10% more willing to gamble your reputation than your peers. The bummer is when these writers get popular they become the objects of critical consensus rather than the puncturers of it and thus lose anything that made them interesting in the first place. Then the cycle begins anew. Lauren Oyler is another good example of this.

I’m also a habitual book starter but I hope you make it through Mason and Dixon, the last 100 pages are the best I think, some of Pynchon’s most beautiful writing which is really saying something.

If you're interested in Strauss I recommend Stanley Rosen's Hermeneutics as Politics (blurbed by John Coetzee!). Rosen was (according to Kojève!) Strauss's smartest student.

I think that for a long time people didn't understand Strauss. They reacted mostly to his students who are relatively normal American conservatives, and not to Strauss. You understand why mainstream liberal political scientists found the Strauss-cult annoying, but his American critics tended not to be interested in why he thought the way he did, why figures like Gadamer and Walter Benjamin admired him etc. Now even the Cambridge School historians of political thought (who were the most anti-Straussian scholars of all in the 70s and 80s) understand Weimar-era philosophy and have started learning from Strauss, which I hope is a sign he's becoming a more ecumenical figure: https://arts.st-andrews.ac.uk/intellectualhistory/items/show/324#lg=1&slide=0