When I was in college I hated lit bros, and I hated David Foster Wallace. My reasons for doing so were at once superficial and quite silly, and profoundly personal. On the surface I had a bad reaction to a short story I was assigned in class, but beneath that I think there was something else going on. I was deeply in the closet about not being a man, and too self-respecting to do the bowing and groveling I perceived as necessary to be a proper male feminist in an academic setting at the time, so I became something else. The last time I talked about crypto-transgender archetypes from a decade ago here I assured you that I was never the Man-Defending-Woman, and I wasn’t lying. There is however a nataly-gendered flip side to the MDW to go with the WDM, something I call the Man-Attacking-Men, and reader- I was absolutely that. Proust says that what you love in another is the image of yourself reflected back at you, but I’ve always thought something like the opposite principle is even truer. What you hate the most is what you see in yourself, even potentially. David Foster Wallace-and by extension his fans- represented everything I didn’t want to be, a supposedly artistic and sensitive but still vicious and predatory man foisting his phallic text on women who just wanted to be left alone.1 The Mary Karr accusations hadn’t become as big news yet as they did in the wake of #MeToo, but Wallace’s demons and the litany of his misdeeds were on display already if you wanted to look into it, and I of course did.

Another reason is that I was maybe a bit of a lit bro myself? Sure, I only ever took two lit courses in undergrad, my favorite living author at the time was Toni Morrison and I loved James Baldwin, the Brontës, and what I’d read of Louise Erdrich, but my favorite author all through college was Borges, I loved House of Leaves and I wanted to write my own incomprehensible postmodern novel the size of a phone book.2 I wasn’t a dick about my tastes, but I had tastes, and they ran in different directions than the smart young literary women I was friendly with.3 If I had been slightly more attuned to myself at the time I might’ve been less freaked out about this, able to realize that I wasn’t a man, and anyway even if I was the sins of every human with my chromosomal configuration needn’t fall on me specifically, but I very much wasn’t. I hated these guys for valid reasons too-it’s not a good thing to be pompous or sex pest-y or to belittle stereotypically female authors and books as some of these guys did-but on some unconscious level I think I was also trying to externalize the sin in which I was implicated by the fact of my birth, trying to wash myself clean of complicity in the horror of the (literary) world.

But enough of my bloviating introspection. Why am I talking about this at all? Over the weekend Rolling Stone (of all places) ran a piece reporting on the denunciation of the “Lit Bro” by the luminaries over at BookTok

“These books are labeled as ‘bro-lit; novels because ‘bros’ tend to find these unlikeable characters incredibly relatable while being unable to acknowledge or even recognize that these characters are intentionally deplorable, thereby misreading the books entirely,” Hower says. “It really is just a harmless way that women poke fun at the books favored by pretentious artsy college boys. If you’ve ever had a pea coat-wearing liberal arts student talk at you about the genius that is David Foster Wallace then you’d call Infinite Jest bro-lit too.”

There have been responses (and a temporal pre-response) from many people I follow, some serious, some less so, all with a certain air of exhaustion, of having seen this play out so many times before. It’s a sentiment that I can both relate to and feel a certain personal guilt about, for the reasons enumerated above.4 For what it’s worth I actually don’t agree with Freddie DeBoer’s assertion that Lit Bro as a social type doesn’t exist anymore in the literary world of 2023-

I can almost believe that someone living in Williamsburg in 2007 lived in a social atmosphere in which they encountered young men who tried to present a very mid-aughts vision of being literary young men through reference to a short list of male authors who share nothing artistically. I absolutely cannot accept that people born after 9/11 have ever lived in those social conditions.5

-but it is a little silly to be treating art bros as a mortal threat to the culture, as though this was still 2013. I’ve seen it argued a couple ways over the last few years that the concept of the “lit bro” and sometimes the art-bro more generally represents an aspect of the shift in cultural valance toward a feminine sensibility amongst the humanities set: a claim I think is correct-women are increasingly the only people who read literary novels, these spaces are increasingly female dominated-but that I’ve never seen laid out in a way that sat right with me.6 On the other hand it also seems clear that this is a human type that continues to exist, continues to evolve. I’ve never met a single DFW-bro (in fact the biggest DFW fans I know are two cis women, an enby and two trans women respectively) but I’ve known several men I’d describe as Murakami-bros over the years.7 As long as people are reading there will be literary snobs, and as long as there are genders in something approaching our current configuration some of those pretentious types will be men. Perhaps they won’t be quite as odious as the lit bro was supposedly, but they will continue to exist as a type as long as literacy in its current form.

This whole discourse feels strangely connected to the pop feminism of the mid 2010s, in some sense a throwback to the moment when resistance to women’s presence in the various cultural Boy’s Club’s was mostly being suppressed, and the gendered makeup of our institutions was the most pressing issue to the clerisy. I imagine this is why the rhetoric of the BookTok-ers in the Rolling Stone piece hit such a nerve with so many actually or unconsciously center-right types: a fairly crucial part of what irritated a lot of non-believing people about that pop feminism and the currents that emerged from it was that your victory lap never ends. You never stop rubbing it in that you’ve won.8 Why should it matter that obnoxious guys with peacoats who smoke outside the library are really into Dave Eggers and David Foster Wallace if what’s left of literary culture and the publishing world in 2023 is so against the kind of “masculine” experimental post-postmodernism lit bros supposedly liked? Probably the American literary novelist under 45 of the moment’s biggest book has a whole aside mocking this type. They lost!

As an art history major, I couldn’t escape them. “Dudes” reading Nietzsche on the subway, reading Proust, reading David Foster Wallace, jotting down their brilliant thoughts into a black Moleskine Pocket notebook.9

The problem with this sort of thing, the issue that feels almost too basic to name but which must be named, is that culture has a shelf life. Infinite Jest is as much a punchline about pretension and lit bros as it is a novel at this point, not so much a status object as something the right-thinking fashionable literary type feels vaguely ashamed of having a copy of/familiarity with. It’s arguably more Homestuck than Look Homeward, Angel in 2023. The same is true for many of the other purveyors of “bro lit” -so called. Time passes, people age, literary fashions change, and at a certain point it behooves an adult to forgive or at least learn to move beyond as much as possible (the minor) slights incurred in our education and upbringings.10 People who are not date rapists enjoy “bro lit” and experimental prose and great length are not inherently masculine characteristics. To believe in the autonomy of art is to understand that the text is different from the reader, although such a belief does necessarily

involve much larger and more abstract questions about the connections (if any) between aesthetics and morality, and these questions lead straightaway into such deep and treacherous waters that it’s probably best to stop the public discussion right here. There are limits to what even interested persons can ask of each other.11

And with that, I leave you.

There’s a semi-viral in its time Electric Lit essay by Dierdre Coyle that opens by fairly explicitly comparing Wallace’s writing to sexual assault before proceeding to a general attack on his literary persona, fans, Brief Interviews with Hideous Men and eventually the idea of men writing about relations between women and men generally

For a long time, I’d respond to men’s Wallace recommendations with “he’s on my list,” or “I’ve been meaning to — totally.” And for a long time, I meant it. Now, thinking about becoming that kind of person makes me feel tired. This is how you become the right kind of person: if you’re not in a position of power, identify your oppressors — well-intentioned, oblivious, or otherwise — and love their art. This is why it’s hard to distinguish my reaction to Wallace from my reaction to patriarchy. This insistence that I read his work feels like yet another insistence that The Thing That’s Good Is The Thing Men Like.

At one time this sort of thing, this rhetoric of “men need to shut up, close their men’s books and listen to the girls” seemed to me quite profound, but now I confess it seems poisonously resentful-if understandably!- in a way that cauterizes the sensibility and leaves one in an unconstructive cul-de-sac of perpetual outrage at the (many and heinous!) sins of literary masculinity. Don’t get me wrong-DFW’s personal behavior was abhorrent, and many men are trash-I just don’t think that’s enough, as I once did, to consign the work to the lake of fire which is the second death.

It’s interesting to note that several of the ‘lit bro” canon authors I’ve never read or don’t like, while the most problematically “lit bro” author I love a novel by (John Barth) never comes up in these discussions because nobody ever reads him anymore.

Even today, probably about a third of my top 10-in which Morrison, Barnes and Lispector get the top picks as novelists-is composed of either bro lit or proto-bro lit (bro lit tends to cluster within the Melville line of what I once semi-anonymously postulated as the James/Melville dyad of American literature, and that happens to be the side I prefer!)

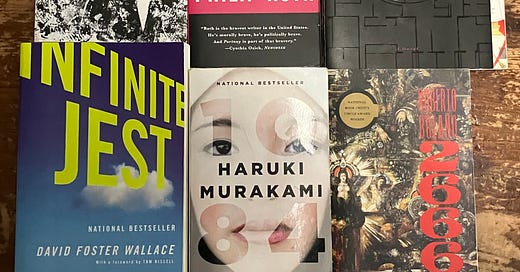

I didn’t start that fire, but I sure didn’t do anything to put it out either. I’ve never read Infinite Jest, but as you can see I own a copy, and I’ve been making my way through the DFW corpus in the last year or so. I almost feel like I owe it to him as a sort of penance.

A much better DeBoer article on this topic would be this one, which connects the phenomenon of pathological DFW-hatred to the officer class’s weak sense of self and an inability to maintain the personal integrity of one’s opinions absent some kind of status game to win.

There’s a type of effete but still cis literary man who complains about this sort of thing a lot-I’m not sure I want to establish a category here like I’ve done in jest before, although the extremely rude phrase “agp masculinism” has been banging around my head for the last few days.

I’m sure this is itself dated now: I know that 1Q84 has its detractors, but to my knowledge it’s never even begun to approach the kind of totemic hate-object status enjoyed by Infinite Jest. My recollection is that the sexism-seeking feminist critics of the era in which I went to school were pretty sure that Murakami was a bit misogynist in the classic “doesn’t quite understand how to think of women as people rather than receptacles for male desire” way (an opinion I may share for the record) but weren’t sure if arraigning him as sexist would count as imperialism against an oppressed denizen of an American vassal state. I think that tension perhaps explains why he gets put with Nabokov in the “fine, but on thin ice” category by one of the figures interviewed for the Rolling Stone piece:

the vast majority of Haruki Murakami’s published works… I don’t immediately consider red flags but if you tell me those are your favorite books then I’m going to have some questions,”

The obvious flipside to this would be that the pop feminist girlboss is herself a figure who continues to be hated wildly in excess of her actual existence and relevance to the culture in the 2020s. If you want to argue that the clerisy of our culture is permeated by a toxic officer class femininity, that’s one thing, but to treat the Broad City-Lena Dunham-Hillary 2016 pop feminist girlboss as though she was still a dominating cultural figure in 2023 is as ridiculous-if not more so-than doing so to the lit bro.

Otessa Moshfegh, My Year Of Rest and Relaxation

Obviously if you were brutalized by a DFW or Hemingway-head I’m not asking you to forgive that, but if your opinion of an entire genre as a thirty or forty year old is formed on the basis of guys you know 15-20 years ago that might be a problem.

David Foster Wallace, Consider the Lobster

Really appreciate this piece, thanks for writing (you get a sub!). The DFW/ lit-bro thing has always struck me as equal parts strange, and sad, strange because it conflates our consumption of art with morality, and sad because all the debate can ever lead to is dumbing down our capacity to be good readers who accept ambiguity in works of art, which degrades something that is fundamentally human.

Also, you touched on it in footnote 9, but the lit-bro/DFW discourse has similarities to the contemporary aversion to Hemingway, which i think is such a tragedy. EH’s work is not of a man proud and secure in his masculinity; it’s of someone trapped by it, and by the expectations in his time for the kind of person he could be. We lose a lot when we decide that writers & their work are only one thing, & not the sum of messy and complicated people.

Anyways i’ll stop there, but thanks for writing this. Excited to read more of your work!

Second essay I’ve read today on this topic, and I’m glad. I’ve yet to finish Infinite Jest and have mixed feelings about it on its own merits, but so far my problems don’t seem to match the ones described in discussions of ‘LitBros’, which has gotten in the way of better, more in-depth discussions about Wallace’s merits and limitations. Appreciate the writeup.