Hi! This week I published the first installment of my reading of Pound’s Cantos, To Lead Back to Splendor. It’s sure to be an interesting journey, be sure to check in with us next Thursday! Today I have some thoughts on Walt Whitman, Albert Murray & the American past and future!

American world-poetry: thoughts on Walt Whitman

I find one side a balance and the antipodal side a balance,

Soft doctrine as steady help as stable doctrine,

Thoughts and deeds of the present our rouse and early start.

I was in the suburbs of Boston over the weekend, killing a little time before I caught the train into the city for a friend’s party at Harvard.1 It was Emerson’s country, but I had Whitman on my mind.

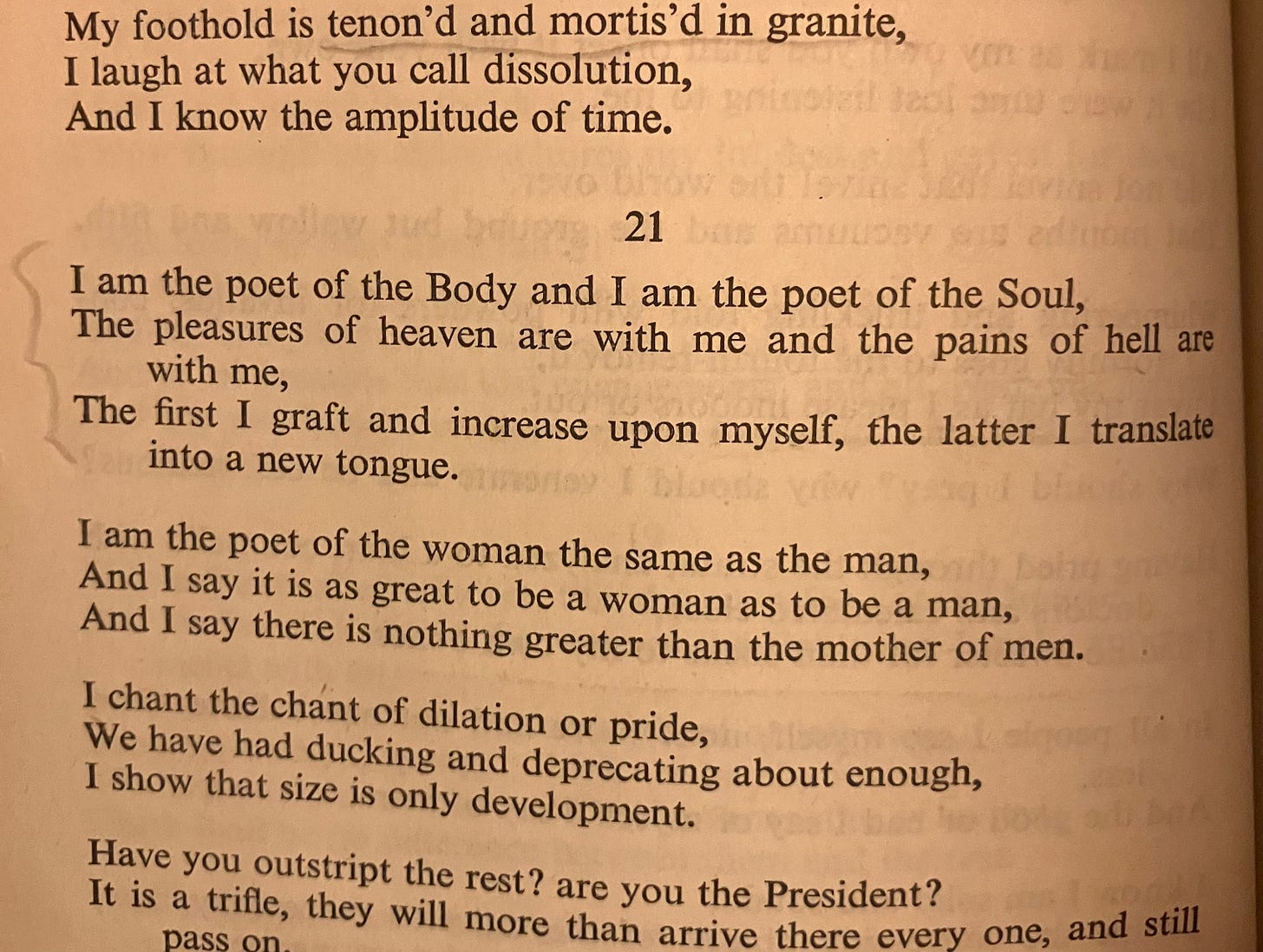

What can be said about Walt Whitman? Imaginative, exuberant, a great innovator, the poet of a cosmic self-love, an eogtist, who is like him in the literature of the world, never mind America? He’s one of those very few, like Hawthorne or Fitzgerald who are probably done an injury by featuring so prominently in literary pedagogy, but how could it be otherwise? He is the greatest American poet, the best claim to representing the voice of the nation in verse, in all our glory and stupidity. Every subsequent poet is judged against him, even many whom I prefer to him. There is simply no other that compares besides maybe Dickinson. The other day I found a midcentury Modern Library copy of the deathbed edition of Leaves of Grass (along with the Selected Poems of Wallace Stevens), and I’ve been perusing it ever since. I reread “Song of Myself,” possibly for the first time in full, although I really don’t remember considering how long ago the last time I read it was.

The Melville collection I covered last week reminded me to investigate Whitman’s book of civil war poetry, Drum Taps, which was included in this particular edition of the book. As goes without saying, it’s impressive stuff, very unlike I was looking at previously. Melville wasn’t exactly writing conventional 19th century poetry-that’s partly why his book didn’t sell!-but the difference is stark. Also fascinating was a prose essay on American poetry, an excerpt of which I will share here:

Infinite are the new and orbic traits waiting to be launch'd forth in the firmament that is, and is to be, America. Lately, I have won-der'd whether the last meaning of this cluster of thirty-eight States is not only practical fraternity among themselves-the only real union, (much nearer its accomplishment, too, than appears on the surface)-but for fraternity over the whole globe-that dazzling, pensive dream of ages! Indeed, the peculiar glory of our lands, I have come to see, or expect to see, not in their geographical or republican greatness, nor wealth or products, nor military or naval power, nor special, eminent names in any department, to shine with, or outshine, foreign special names in similar departments,— but more and more in a vaster, saner, more surrounding Com-radeship, uniting closer and closer not only the American States, but all nations, and all humanity. That, O poets! is not that a theme worth chanting, striving for? Why not fix your verses henceforth to the gauge of the round globe? the whole race? Perhaps the most illustrious culmination of the modern may thus prove to be a signal growth of joyous, more exalted bards of adhesiveness, identically one in soul, but contributed by every nation, each after its distinctive kind. Let us, audacious, start it. Let the diplomats, as ever, still deeply plan, seeking advantages, proposing treaties between governments, and to bind them, on paper: what I seek is ditterent, simpler. I would inaugurate rom America, for this purpose, new formulas-international poems. I have thought that the invisible root out of which the poetry deepest in, and dearest to, humanity grows, is Friendship. I have thought that both in patriotism and song (even amid their grandest shows past) we have adhered too long towards petty limits, and that the time has come to enfold the world.

Once more, what to say of him? I suppose that as with Emerson a part of me worries that such genius is beyond us, wonders in my more pessimistic moments if that spirit hasn't left us entirely. Perhaps something has been lost in the translation into American modernity, but we are modernity's nation after all. Perhaps it's middle age, the paunch accumulating around the midriff of a culture. The same Boston suburban region that produced so many of the luminaries of nineteenth century letters is that which formed the Bronze age Pervert in our own. Is it possible that that light shining out of Concord, out of Whitman from New York was merely the first flush of youth, that we now find ourselves in an uncertain dotage as the rest of the world either catches up or proves us to have been nothing more than a failed experiment on a continental scale? These are thoughts I sometimes find myself thinking these last few years. I understand in a way why the Claremonsters are so dead set on RETVRNing to the 19th century, but then you never can do that, to any time really.2 We were young then, our path undetermined, our roads unpaved. We are old now, even if Europe and Asia will never see it that way, even if we had a good run, even if we go on for another century or two something is still gone which can never be recaptured.3 Worldliness is not lost once it has been acquired. You want it back when it's gone, I write without having yet lost it, but still I recognize dim traces of creation. Mostly I do not feel this way, mostly I am as most of my countrymen what a European might call "delusionally optimistic." We all have our gloomy moments, some of us more than others.

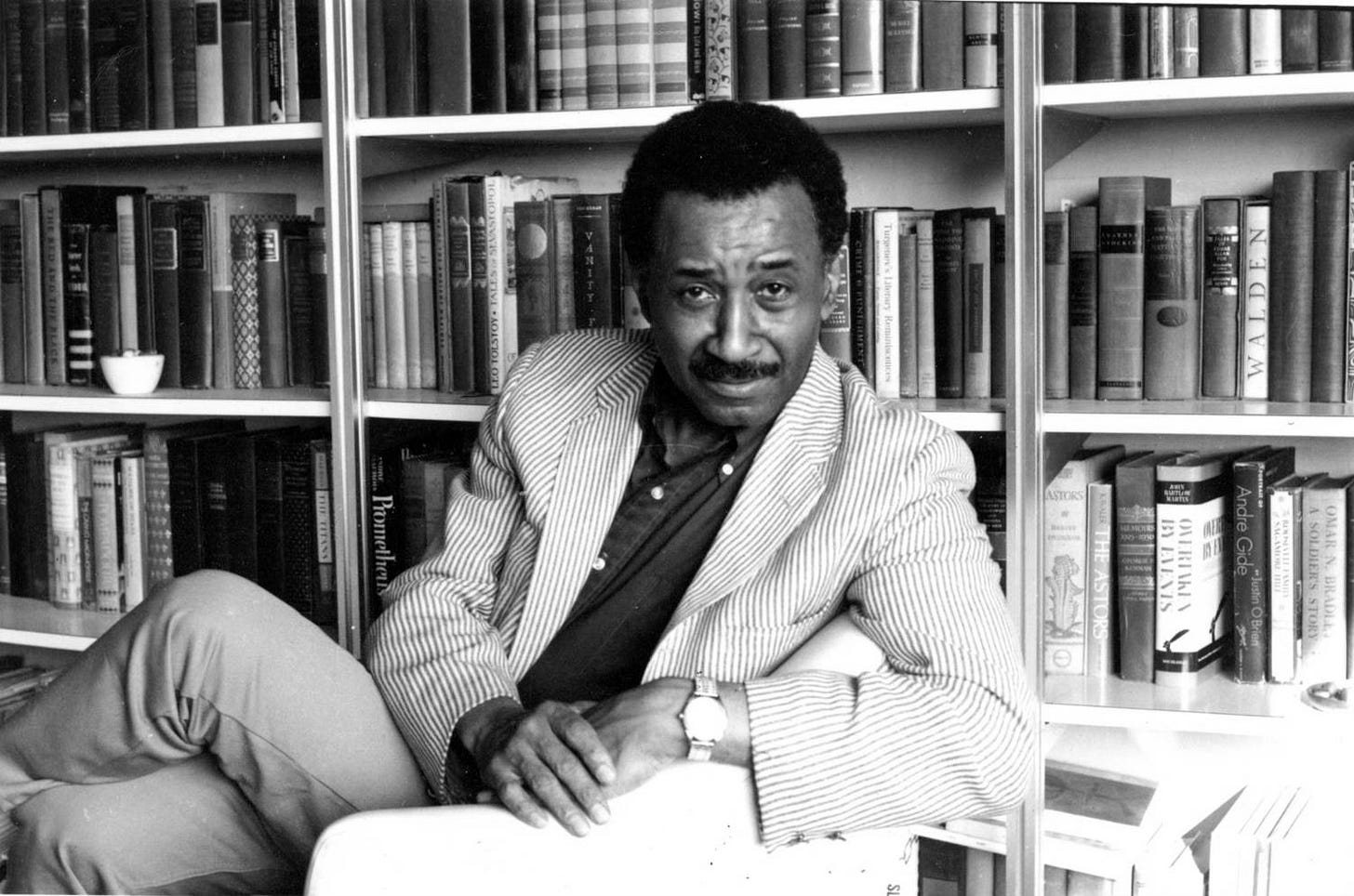

Idiomatic Blues: more (very) inadequate thoughts on Albert Murray

I’ve been sporadically making my way through the remainder of Albert Murray’s Library of America edition for the last two years. Murray was a fascinating figure, a close friend of Ralph Ellison and a novelist and distinguished critic in his own right. I was revisiting The Hero and the Blues the other day. It should be much more widely read than it is, a concise work of theory offering a unique description of what Murray called the “blues aesthetic” in literature.

Indeed, as every schoolboy should remember easily enough, to aspire to heroism is to wish for the adventures of Ulysses, the obstacles of Hercules, the encounters of Sir Lancelot—and so on, to the predicament of Hamlet of the poverty and isolation of Stephen Dedalus

I also highly recommend the Omni-Americans, a fascinating, slightly heterodox take on race relations circa 1970 that is well worth your time, as well as various essays on music and the 1976 book Stomping the Blues. I’ve been trying to write an essay about Murray for ages, but I can’t seem to find the right hook, so for now you’ll have to settle for another minor round of my pushing his writing.

The party was good, a lot of very bright people, one of whom was trying to persuade me to go to divinity school if I went back, which is of course one possible path.

This is not the subject of this digest by any means, but it is worth noting how unbelievably corrupt nineteenth century politics was, nostalgic though we are now in these atomized times for urban machines and mass church attendance.

I have a vivid memory of a Dutch professor saying (of which city in the Netherlands I’ve forgotten) “that’s a very new city, it was built in the 1500s!”

whitman said “i was simmering, simmering, and Emerson brought me to the boil.”

i had an epiphanic morning on a sofa in Nice reading the 1855 edition straight through, before, during, and to the end of, a sunrise