Which is all of the story, like a torn papyrus. That is how the past exists, phantasmagoric weskits, stray words, random things recorded. The imagination augments, metabolizes, feeding on all it has to feed on, such scraps.

Hugh Kenner, The Pound Era

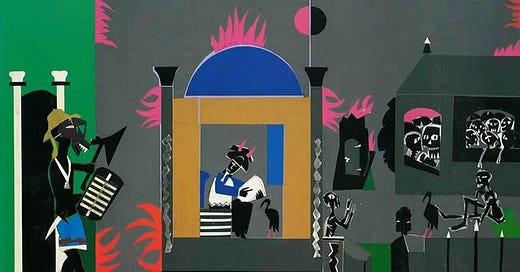

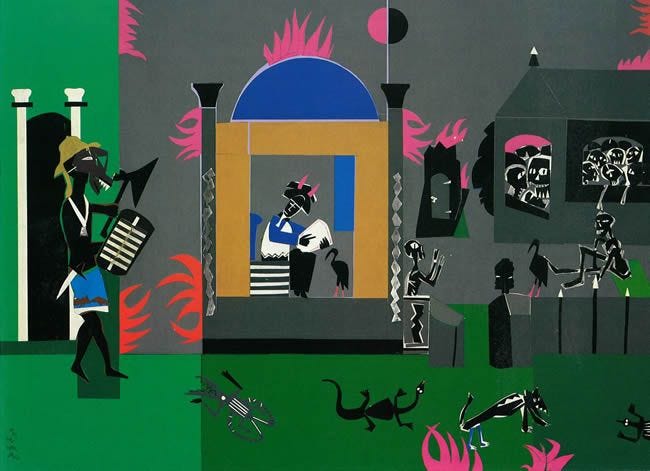

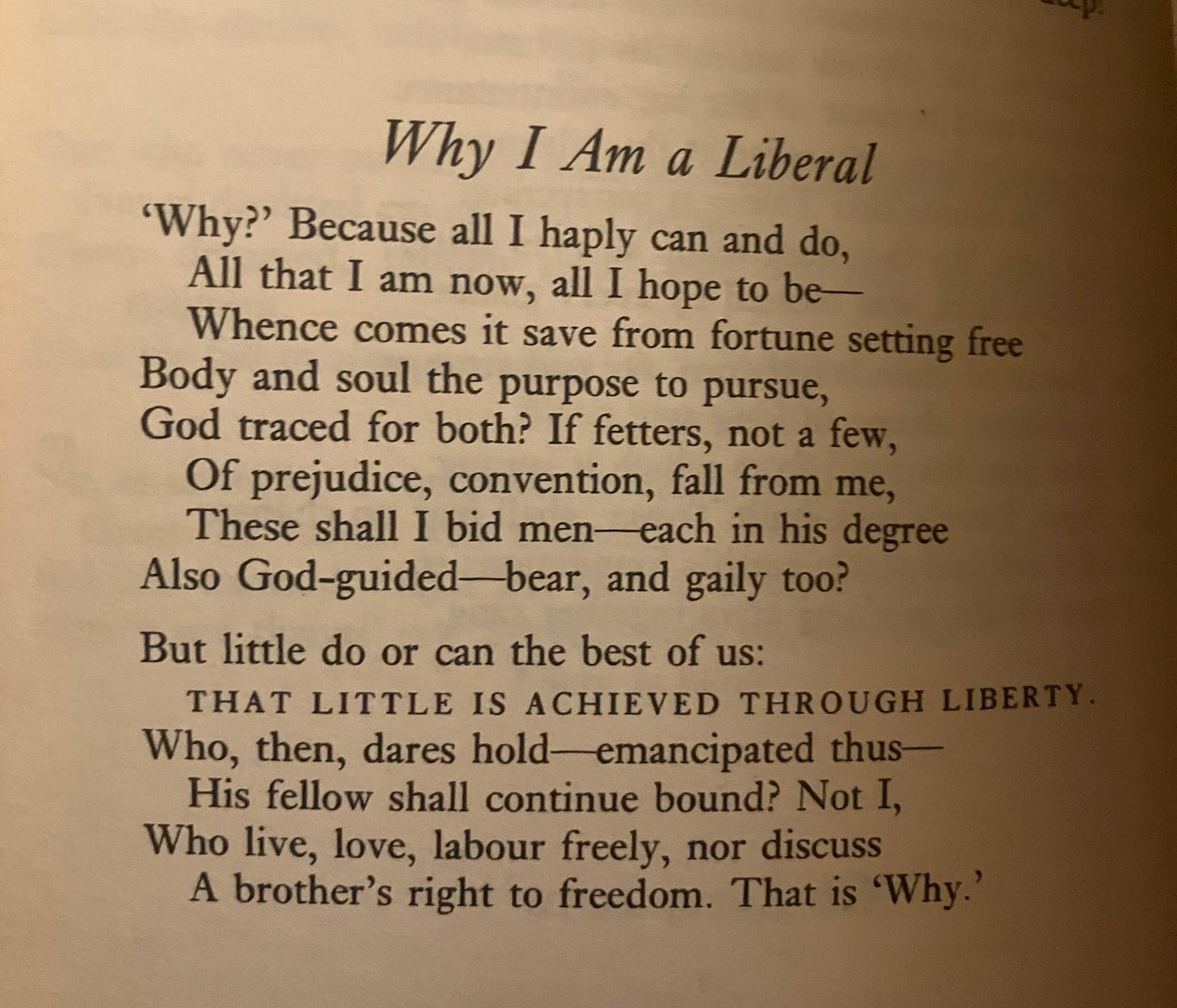

Ezra Pound's Cantos famously begins with a rewrite of a renaissance-era Latin translation of the nekuia episode of the Odyssey, which cites itself, crediting the translator amongst the apparitions of the dead. The Cantos are largely composed of this kind of miasmic appearance of the dead or the living-appearing dead, and in some ways over the course of the later sections Pound becomes one of them, a grey shade hanging back, circling, full of anger and regrets unwilling to approach the blood, unable to find release, unable to make it all hold together. In the second canto the shade of Robert Browning, possibly the central influence on Pound and many of his contemporaries makes his appearance, and reference is made to a long poem of Browning's that I have never read and I'm not sure is even in print today-much his longer work is not. My observations here will be fragmentary, much as the poem is, one of its most impressive attributes being the way time appears suspended for the duration, ancients and moderns and medievals meshing on the page.1 In Joyce and indeed in Browning the feeling of the Mediterranean is one of moderation, tolerance, liberalism.

Pound lives in a different time from Browning and a different Italy from Joyce. His is closer to the Rome of the empire, although I'm not sure if when this was written the love affair with Mussolini had yet begun. We are perhaps closer to the Italy of Thomas Mann, full of intrigue, phantasmagoria, not an entirely wholesome place, although there is a certain dubious orientalism(?) to both of his major stories set in the country which is quite alien to Pound, and which casts a shadow on those works. I am reminded perhaps only situationally of Aaron’s Rod, D.H. Lawrence’s 1922 novel set partly in postwar Italy, one of his more Nietzschean or fash-curious novels and also one of his gayest, laden particularly toward the close with a homoeroticism which threatens to bubble up in a quite shocking way, considering some of the author’s views. Pound has nothing of the sort here but still, something reminds me here. Lawrence was perhaps in some respects spiritually an American, too much so to have been allowed to die in Taos New Mexico and be scattered amongst the scorpions and the cacti. The world dislikes that sort of neatness until the moments when it fulfills the most unbelievable contrivances, as if thumbing its nose at our endeavors at understanding.

The influence of Neoconfucian thinkimg on Pound is also a question mark for me. Master Kong makes an appearance in Canto XIII, and a particular interpretation of the Confucian antipathy toward commerce is arguably deeply consequential for the poem as a whole. In many ways the central major concern of the poem is the reckoning with the first world war as a totalizing calamity. Hugh Kenner makes some fascinating and extravagant claims about what the 20th century could have been without the war in The Pound Era, although how much and if Pound held similar beliefs I am uncertain. Nonetheless his quest to find a cause for the war, and the answer he arrived at, is the major theme of the Cantos. Quoth Kenner:

The Ur-Cantos, written before the encounter with Douglas, were put by till he could rethink the long poem's direction. Its scope, when he finally clarified it, was to be nothing less than a vast historical demonstration, enlightened by Douglas' insight; the first I6 Cantos, the first published unit of the poem, march straight from Homer's time, and Aphrodite bedecked in gold, to the World War which came about because gold was misapprehended.

The design is at this stage not yet apparent, but I'll attempt with some help from Hugh Kenner to enumerate. During the interwar period Pound fell under the sway of the unorthodox economic theories of a certain Clifford Hugh Douglass. I am no economist, and so I'll take Kenner's word about what he thought. Here's how it's briefly laid out the second time the theme arises in The Pound Era:

the Douglas hypothesis, that the money distributed by production will not buy the product, means that there is a perpetual shortage of money. This shortage must be made up by creating money. The money is created as interest-bearing debt: this, and not any quibble over interest rates, is what Pound means by usura.

The money is created without regard to need, but only with an eye to (I) generation of interest, and (2) in case of foreclosure, salability of the security.

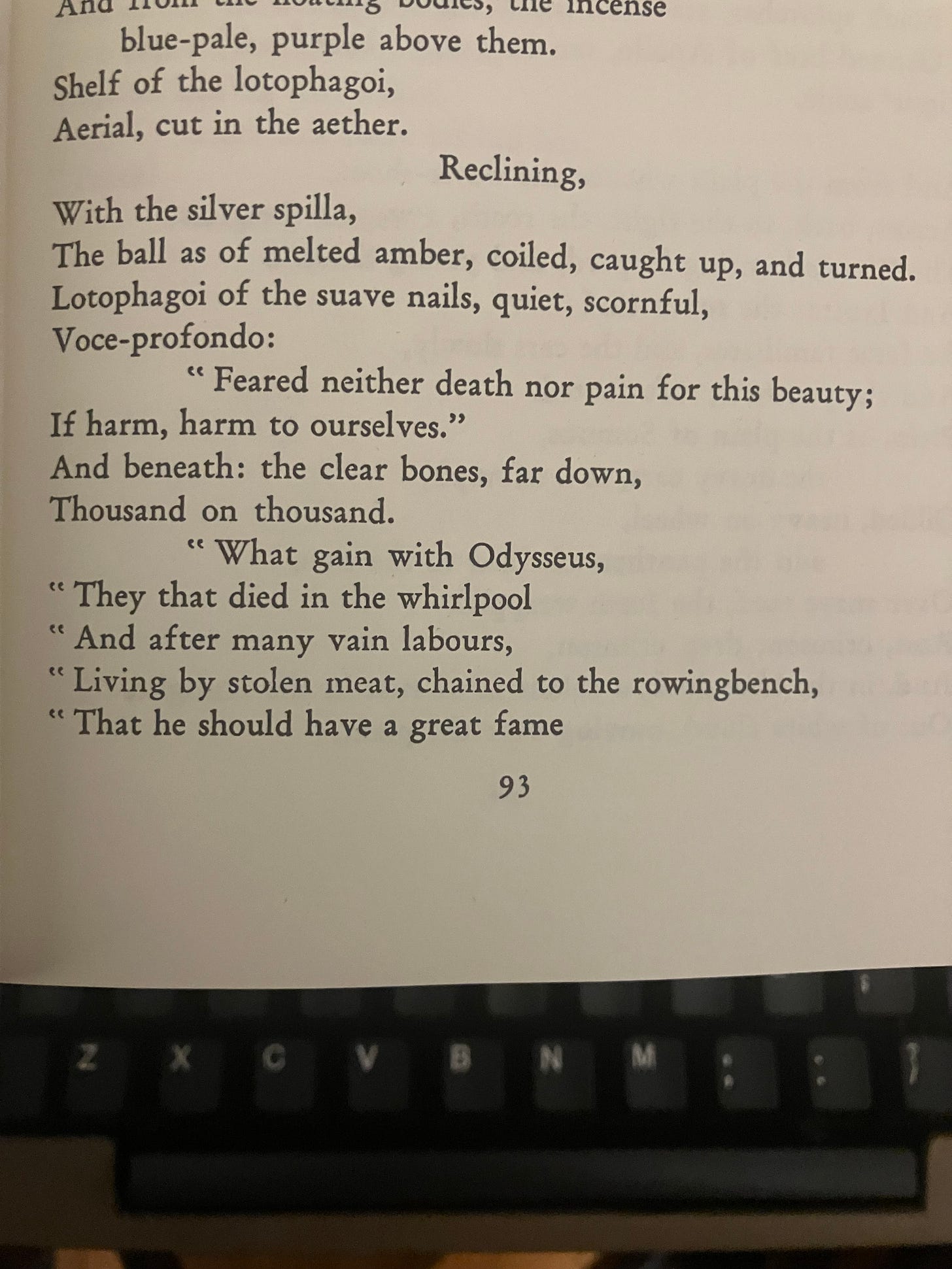

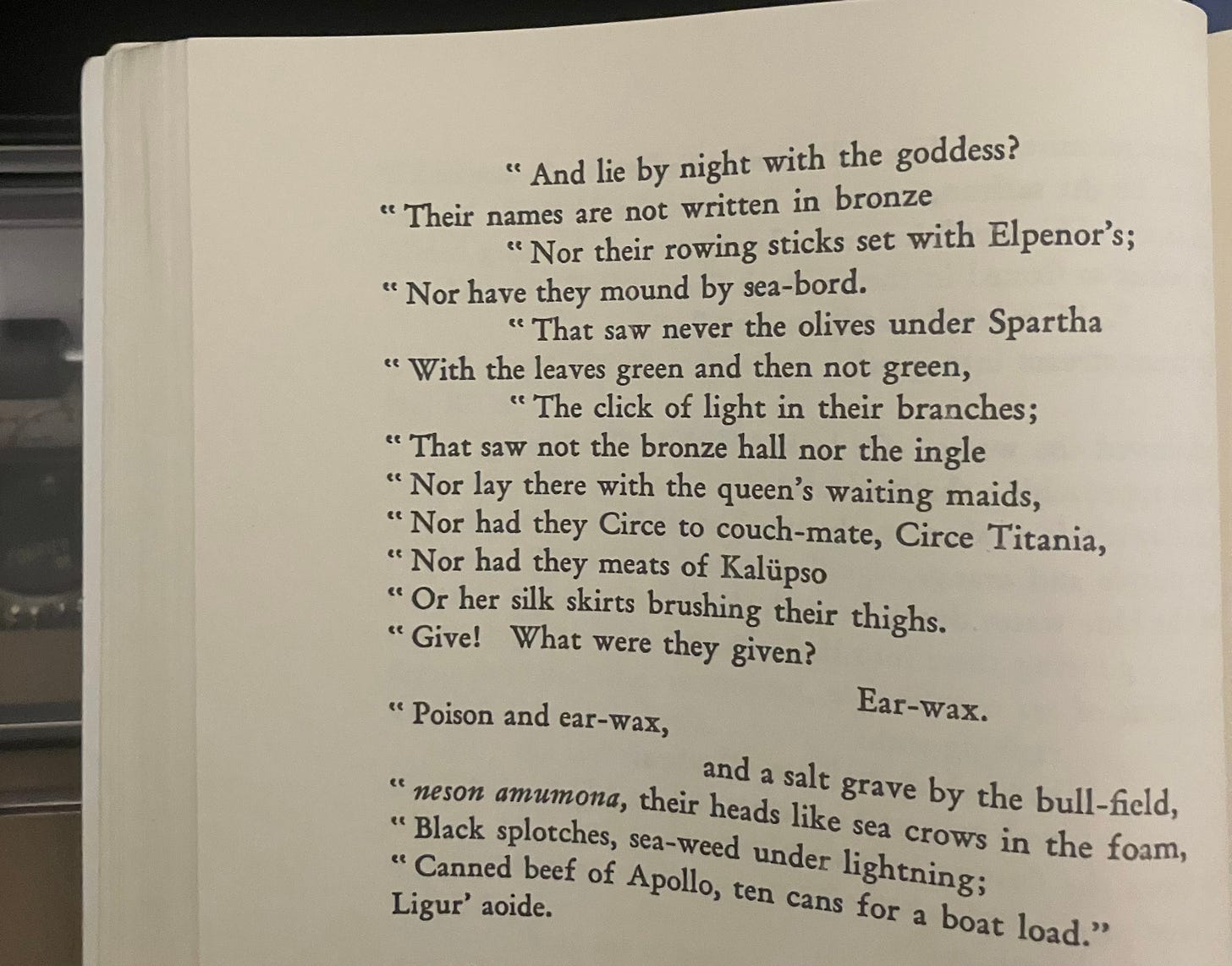

Throughout the Cantos maddening inconsistency rules the day, which I have read enough of the rest of them to know never changes. Passages of unbelievable beauty coexist with length discussions about episodes of Italian history I know nothing about.. One of my favorite segments is in Canto XX, a bitter lament for Odysseus's lost crews and the cost of that glorious foundation of the western literary tradition.

Perhaps a cry for the lost generation of which Pound was a part?

The absence of time in a linear sense in this poem is partly predicated on a sort of esoteric perennialism about which I will say more in a subsequent installment, suffice to say that it involves the troubadours and the Eleusynisn mysteries. As I thumb through The Pound Era Kenner shames me for not having read the Golden Bough.2

For the gods persist. James Frazer, later knighted for his insight, published The Golden Bough when Eliot was two, Pound five. Christ is Tammuz again; the personnel change, the names of the gods mutate, but the cults have analogous impulses, stubbornly conserving. Eliot specified in the notes to The Waste Land not only his poem's indebtedness to that book but his generation's; and viewing at Rapallo every July votive lights set adrift in the Golfo di Tigullio for the festival of the Montallegre Madonna, Pound wove into it cries of "Tammuz! Tammuz!!" and affirmations that Adonis was commemorated still:

I mentioned this in notes, but I've opted to walk back the decision not to use guides already on account of just how much Italian renaissance historical info there is in the poem. I can identify the references to neoplatonists ancient and early modern, and I know what he's talking about in the voice of the troubadors in the famous passage about being called a Manichee, and there are copies of Pico and Vico on my shelf, but about half the time I have absolutely no idea what Pound means by this or that reference to a condottiero or some Neopolitan political faction of the later 14th century. This post is mostly flying blind, but from next week on I hope to be better informed about the allusions to sigismundo or the various financial transactions of this or that aristocrat. The impression from much of that material is Robert Browning in modernist drag if "My Last Duchess" was concerned not with the Duke's killing of his previous wife, but rather the accounts held in a Florentine bank and the amount paid for the portrait of her on the wall.

It's very difficult to judge any one section of the Cantos in isolation, this being true even of the segments such as this and the Pisan Cantos which function more or less as standalone poems. I'm loading up on secondary materials, and next week's set of cantos is short enough that I may try to do two of them in one installment. We'll see! Let me know what you think of today's post, and I'll see you tomorrow for the weekly digest, which I suspect will be primarily poetic once again, although I've not sat down to write it yet and don't really know how it will wind up. Cheers!!

Reminiscent in some ways of Allan Moore’s approach in his greatest works of the 1980s and 90s, although I may just have him on the mind, given that I had a breakthrough on a long-gestating review last night.

I’ve read a great deal of literature derived from it, but never the original.

Very enjoyable. Are you familiar with Jacob Burckhardt's book, Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy? Might help illuminate the condottieri and all that.

This is great! Looking forward to your thoughts on the influence of perennialism. Frazer, I find, is eminently skimmable, 12 volumes of examples—the table of contents tells the whole story. And yet the argument is rather elusive—a scientific flaw but a key to the work’s cultural impact, allowing it to be read against the grain of the author’s rationalist aims