Welcome back friends, to what I hope to be the default form of these posts over the next year. I’m not sure I’ve got weekly posts in me the way I did for part of last year-at least not while I’m working on my novel-but I’m aiming to put out digests like this one a couple times a month moving forward.

Comic books and other such trifles

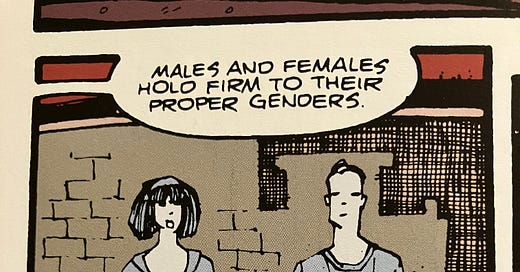

Probably the main news in comic land was that I finally got around to reading the late Rachel Pollack’s 1992-95 run on Doom Patrol. It’s fine stuff, less memorable panel to panel than Morrison’s immediately preceding run but maybe better plotted and more coherent as a whole. It takes a bit to really get going-those first few establishing arcs feels very leftover-but when Kate Godwin mostly non-used alias Coagula, a transgender woman with coagulating powers joins the crew things really pick up, and what follows is a fun, idiosyncratic run on the comic, suffused with 90’s new age stuff and Jewish mysticism. Kate is in many ways the central character of Pollack’s run the way Crazy Jane was for Morrison’s, and she’s a welcome inclusion, underlining the sometimes queasy way Morrison wrote Jane and Rebis.1

Pollack does a good job with Dorothy as well, fleshing her out a bit in the first few arcs and making her the unofficial leader of the Patrol following Caulder’s betrayal at the end of the preceding run and resurrection as a severed head. As might be expected she’s very interested in the Doom Patrol as queer bodies in a way that makes good on a lot of the promise of Morrison’s run and the premise thereof without quite succumbing the way it occasionally does to anxiety of influence regarding the X-Men. it’s fun, I might write it up in more detail at a later date.

All in all Pollack’s run isn’t quite as consistently striking as Morrison’s, but the two big arcs-the Tiresias War and the penultimate (the comic ended with a mostly unrelated one-shot about Y2K and an obsessed fan realizing too late that his ordinary life wasn’t so bad after all) arc about an evil undead Rabbi trying to heal creation with an impure motive are as good as or better than anything they wrote, and her version of Doom Patrol has a stronger sense of what it is. Too often Morrison’s Doom Patrol feels like a dry run for what they’d explore in Invisibles, while Pollack’s run for all that it live in comparison to what preceded it stands magnificently alone.

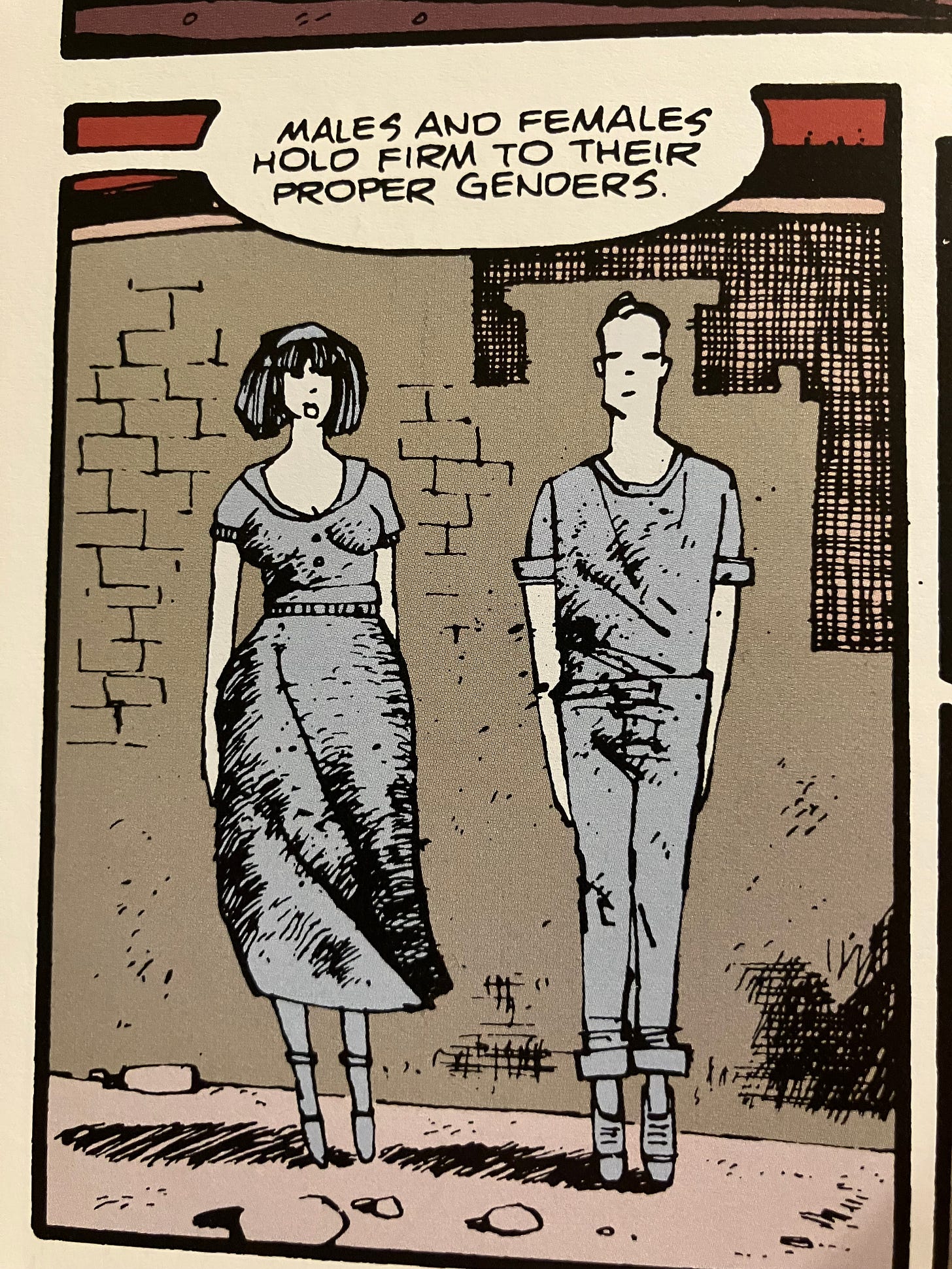

Speaking of Morrison, I reread their All-Star Superman, a loving one-off non canonical run on the character that makes for a fascinating pair with his often brutally cynical deconstructionist take on New X-Men. The best takes on Superman always understand that there are two essential qualities to a good superman plot- firstly he is that good and secondly, the weirder the better. Grant Morrison is very capable of weird and strikingly effective at #1 as well.

Brit lit: Mitchell and Woolf

I reread Mrs. Dalloway, a thrillingly amoral novel that transcends its canonical reputation more than anything I can think of off the bat besides maybe some Melville. I’m not sure I can completely endorse Woolf as a realist-one is always aware with her that we are observing constructions, impressions of what others might be, exquisite sculptures yes but animated and propelled by the same unitary mind. There’s something slightly Dickensian about her for me in that way, which is odd because he’s all surface and she’s all depth, but it’s maybe in the way that a certain unreality is for them the most real thing, the most alive for being dead matter animated by creative demiurgy. To maybe steal a bit from the next one of these (whenever it comes out) this passage about Septimus returning to the great works after the war has always stuck out to me in its essential truth-which is probably like many great truths a gruesome over-generalization.

Here he opened Shakespeare once more. That boy's business of the intoxication of language—Antony and Cleopatra—had shrivelled utterly. How Shakespeare loathed humanity—the putting on of clothes, the getting of children, the sordidity of the mouth and the belly! This was now revealed to Septimus; the message hidden in the beauty of words. The secret signal which one generation passes, under disguise, to the next is loathing, hatred, despair. Dante the same. Aeschylus (translated) the same.

I’ve also (re)read(?2) David Mitchell’s 2004 novel Cloud Atlas, one of the literary classics of our young-ish century, a matryoshka of subtly interlocking narratives spanning time, space, & fiction itself. It’s curious to compare this (I haven’t seen anybody do it, but I’m sure there’s loads of more intelligent commentary out there) to Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go, which I read last year, especially since both tackle the subject of dehumanized slave-clones. I’ve since taken down the post in which I discussed that book, so I’ll insufferably quote myself to you:

I’m not sure I’ve read enough of either’s corpus to make this argument credibly, but there’s something in Ishiguro that reminds me of Thackeray, especially the Thackeray of Vanity Fair—in both one has a sense of the English realist novel unmoored and decentered, “living without God in the world.” Kathy H. might not be as ruthless or amoral as Becky Sharp, but hers is a later age that can more truly inhabit the adage of a “novel without a hero” an age without any prospective avenue of escape or even the consciousness that one could exist in some religious or Fisherian sense. I’ve struggled with this side of Ishiguro-the nihilistic quietism- in the past, something I (not entirely successfully) tried to elucidate last week. Even if it is true, it seems to me a crushed, defeated way of viewing the world-the Nobel committee described him as Austen meets Kafka, and I think perhaps he captures something of the problems I occasionally have with both of them-the stifling, insular domesticity of Austen and the enervating sense that in modernity one cannot really finally do anything that one gets at times from Kafka. It’s funny, because I’m not usually a vitalist this way about fiction, but there is something here I revolt against on a fundamental level, despite that Never Let Me Go is a masterpiece.

I find it interesting how Ishiguro and Mitchell invert the superficial aesthetic one associates with the form of their respective works, Cloud Atlas with its interlocking (and to a surprising number of readers, incomprehensible) postmodern structure preaching ultimately a liberal middlebrow gospel while Never Let Me Go erects its cathedral of Great Tradition Austenian English realism against the posthuman abyss & emptiness of all human hope for liberation that it seems to argue lies in our future. There’s an understated spirituality to Mitchell’s novel, a theme of reincarnation and eternal recurrence weaving through the stories

Q: Is there a meaningful distinction between one simulacrum of smoke, mirrors + shadows—the actual past—from another such simulacrum—the actual future?

One model of time: an infinite matryoshka doll of painted moments, each “shell” (the present) encased inside a nest of “shells” (previous presents) I call the the actual past but which we perceive as the virtual past. The doll of “now” likewise encases a nest of presents yet to be, which I call the actual future but which we perceive as the virtual future.

NLMG is the better book- Cloud Atlas is great the way much of Dickens is, without being Great-but all the same I wonder if Mitchell might have the last laugh, might still be a prophet of our times. The jury’s maybe still out on the liberal sermon stuff, but the last couple hot literary novels I’ve read-Lockwood’s No One is Talking About This, Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation, Lin’s Leave Society-all seemed to point toward a renewed spirituality or transcendence of the novel, whether through aesthetics, community, or actual spirituality, which Cloud Atlas perhaps pointed toward in its way back in 2004.

Strip back the beliefs pasted on by the governesses, schools, and states, you’ll find indelible truths at one’s core. Rome’ll decline and fall again, Cortés’ll lay Tenochtitlán to waste again, and later, Ewing will sail again, Adrian’ll be blown to pieces again, you and I’ll sleep under Corsican stars again, I’ll come to Bruges again, fall in and out of love with Eva again, you’ll read this letter again, the sun’ll grow cold again. Nietzsche’s gramophone record. When it ends, the Old One plays it again, for an eternity of eternities.

Some sympathetic musings on Dave Hickey and what he might or might not need to be saved from

I’ve read Dave Hickey’s The Invisible Dragon and been thumbing through Air Guitar in response to

, Blake Smith, John Pistelli and Paul Franz’s symposium of the last few months. I’ll confess to being largely unfamiliar with Hickey up to now-I was almost an art history minor, but I was more ancient and premodern art anyway-but I can see the appeal. If nothing else I recognize in him an honored predecessor, someone doing a fundamentally similar thing probably far better than I do. As Blake so admirably puts it:Hickey celebrates talk against what he calls writing—the officializing, normative, institutional, theory-driven attempt to codify the vitality of our ongoing, primordial immersion in discourse about art, that is about beauty and ugliness, into something meant to be permanent.3

I’ve been fascinated reading (and listening to) the symposium- Smith’s analysis of the contention that Hickey needs to be queered and saved from his masculinity, Pistelli’s exploration of gender and capitalism in Invisible Dragon, Oppenheimer’s musings as the guy who’s written a book on the man!

At the risk of throwing my philistine hat into this melding of highflying aesthetic considerations I’ll thrown down a no doubt troglodytic and already contained in the subtlety of my predecessors but nonetheless pressing thought. For me, the thing that Dave Hickey has to be saved from is poptimism. Something like it at least, that sense that he shared with his older and younger contemporaries the early Susan Sontag and Camille Paglia that there was some vitality to mass culture that could offer Beauty, could save us from the killing intellection of the twentieth century “therapeutic institution.” This belief in the magic of the markets, in pop’s ability to save ourselves from our own minds is one of those ubiquitous dreams of the turn of the century that continues to taunt from the wreckage of our hopes, still on occasion able to stir us from our boredom but more often than not offering only further alienation. On the other hand Hickey seems to understand as so many of those who followed him didn’t that this is in some form a retrospective process, as he writes in the long fifth essay attached to the 2012 rerelease of the Invisible Dragon (the one I read):

In this ragtag manner, the beaux-arts sensibility saves what can be saved, piece by piece, through hoarding, thrift shopping and dumpster diving. Everything stolen is in some sense memorable, or else it is forgotten.

This in my view is what the hegemonic poptimism of the moment forgets—exactly that we can only identify the great pop art in retrospect, that it’s nearly impossible in the moment to tell what will pass and what will endure, and that the quest for beauty necessarily includes critically sifting through a lot of discarded crap! I’ll probably revisit this thought at some later date when I’ve got my hands on the 2023 edition of The Invisible Dragon.

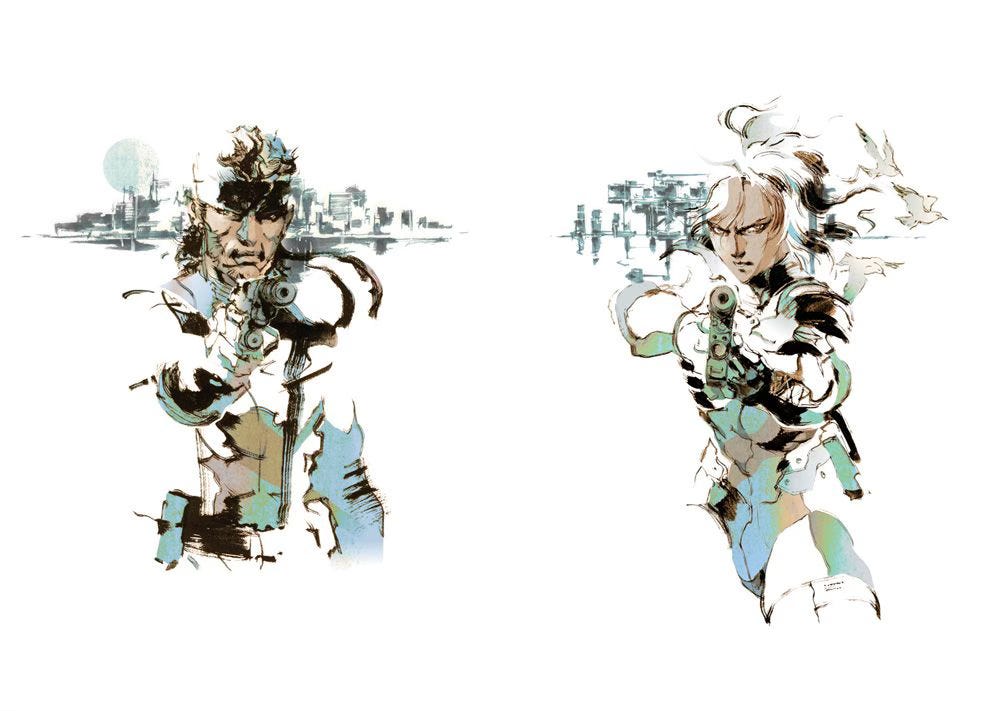

Ephemera: “Raiden, turn the game console off now”

I probably don’t agree with the stance that video games aren’t art, although I do understand where it comes from.4 I love a lot of games, but the number I’d describe as art in the same way as my favorite novels, films, hell even my favorite albums is pretty small considering the number I’ve played. There are plenty of games that are great experiences, but not many I get as much from as a Proust, Dickens or Toni Morrison novel, or even some of the better popular novels (yes reader, I am a snob. I assume it’s why you’re here.) In the past I’ve occasionally speculated that this is related to the lack of much of an auteur tradition in gaming, although I’m not 100% sold on that being the case anymore. That said, I’m always willing to make exceptions for any given rule, & Metal Gear Solid 2 is one such game, turn of the millennium hysterical realism a la Wallace and Pynchon filtered through Tom Clancy type military fiction and eighties action movies as viewed by Japanese eyes. I’ve played a bit of it myself ages ago but for the record it was watching my friend finish the thing while I read A Little Life that I mostly formed the impressions that make up the flesh of this little capsule.5

A somewhat contentious sequel to a beloved modern classic in its own time, MGS2 has aged for the most part brilliantly on a thematic level, its bewildering left turns and double-crosses sometimes nearly incomprehensible and yet sublime (and often made actively less so by the plot of its sequels.) Frankly, I don't know how to do it justice at all. The AI rant from the end of the game is rightly notorious, and regrettably comes to make more and more sense with every passing year.

Everyone withdraws into their own small gated community, afraid of a larger forum. They stay inside their little ponds, leaking whatever "truth" suits them into the growing cesspool of society at large. The different cardinal truths neither clash nor mesh. No one is invalidated, but nobody is right. Not even natural selection can take place here. The world is being engulfed in "truth." And this is the way the world ends. Not with a bang, but a whimper.6

And with that yet again I leave you.

Something about Morrison’s gender explorations is that while you’re always supposed to understand that he’s pointing to Lord Fanny or Danny the Street and saying “actually she’s me” they also clearly get off on the abjection of it all, there’s a very vampiric element to so much of it. *I* don’t really mind this-as I’ve written elsewhere I don’t think you can ever get the discomfort out of these things, and I do think there’s often a vampiric quality to the explorations of gender and sex early on in the process of working out one’s identity, but that said I completely get why some other trans people have an issue with Morrison.

I’m fairly certain I read the book when I was much younger and it was much newer, and yet rereading it I found that the only parts of it I remembered were the Pacific Journals of Adam Ewing and little bits of the First Luisa Rey Mystery and An Orisen of Sonmi chapters. It would have been in the era when all fiction was equal to me, when Michael Crichton and Charles Dickens and Tom Clancy and Dorothy Sayers and all the mass of received literature that crossed my path was just a mass differentiated only by my individual discernment. In other words, before I was a snob.

I love the ambivalence of this essay, the way he’s simultaneously celebrating Hickey and snobbishly, intellectually repulsed by this mode, annoyed by it, etc. I relate even if I’m probably much closer to Hickey than Smith’s verbal eloquence and Arendt citations!

I love and hate talk as Hickey celebrates it—being a fan of being a fan—and I dread the implications of imagining that it is not just the energy in which we live, but something to be abstracted from that living and upheld as good

To say nothing of the line about the two genders-Lord knows I’ve been both the boyfriend subjecting her poor girlfriend to Tales From Topographic Oceans and the woman gritting her teeth at nerd friends watching Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith. Both me indeed!

Strangely this has been on my mind lately. This article crossed my notes the other day, just a few hours after I was having an irl variation on this discussion.

I gotta quit playing video games. I’ve known this for years—if I’m ever going to be the writer I want to be it simply must go. But there’s knowing something abstractly and there’s feeling the acute damage it’s doing in real time.

That I can certainly agree with. I’ve massively cut back on my own gaming hours in the last three years, partly admittedly for unrelated personal reasons-I have an essay floating around in drafts titled something like “My Kevin Smith Years” and I’ll leave the thought at that for now-but also because at a certain point it came to feel, to be quite frank like a waste of time that I no longer had so much of as in prior eras.

Watching a friend play a sufficiently interesting game is a very peculiar aesthetic experience in itself, and one that I’ve never seen written up at any real length. It might be a little too postmodern to do justice to, who knows!

It should be said in a trolling spirit that the plot of MGS2 revolves around a war criminal former president of the United States launching an insurrection against the nonhuman intelligences that really control the world, an insurrection the player is forced to quell partly because said president is such an asshole, and partially because there was never really a choice, Jack. This was originally going to be more central gag to the discussion of the game, but I desperately want to move away from these political semiprovocations, so into a footnote it goes, and may God have mercy on all of our souls this year.