Philo-Aesthetic Digest 2/28/25

Hi! This week I announced a public blogging-through of Ezra Pound’s Cantos over the next month or so. Today here are two short pieces on two of the American greats, Herman Melville and Bob Dylan, and a brief aphoristic middle. Enjoy!

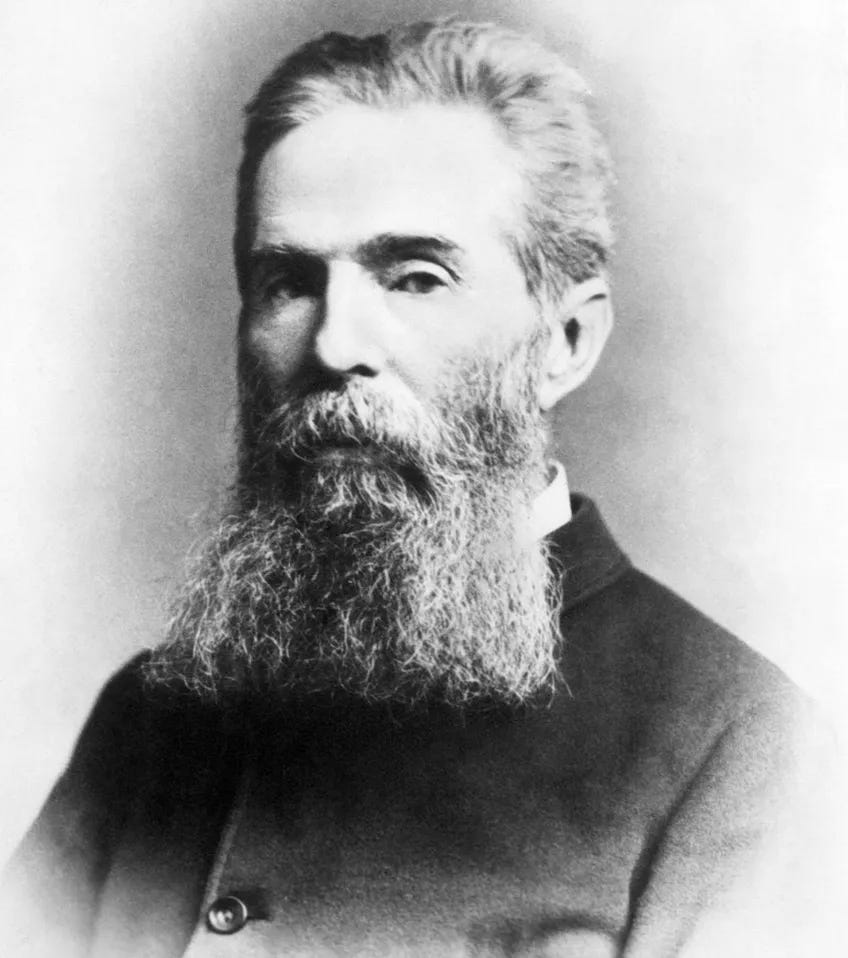

Herman Melville’s literary output over the near quarter-century after The Confidence-Man ended his main sequence of novels consists of three poetry collections, a massive semi-autobiographical epic poem entitled Clarel, and a fragmentary and unfinished short novel. This novel, Billy Budd would eventually be hailed on its disinterment in the 1920s as a true American classic, probably Melville’s best known book aside from Moby Dick. Recently I’ve been reading through Melville’s poetry volumes, handily collected in a now shamefully out of print Library of America volume. The first of these, the 1866 collection Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War, was by far the most successful of these, although it was itself a failure, and Melville’s subsequent efforts would be largely vanity publications.

But Splendors wane. The sea-fight yields

No front of old display;

The garniture, emblazonment, And heraldry all decay.

The tone of the various poems that make up Battle-Pieces is probably best described as “ambivalent Yankee triumphalism”

This is an affect that is liable to seem for various reasons strange to us in our present condition.The meaning of the American Civil war-and its less glamorous second act, reconstruction-has been much debated over the last century and a half. Sometimes envisioned as a righteous crusade, other times as an unnecessary tragedy. We are accustomed to thinking of the conflict in the former terms these days, and discounting the human cost as simply the necessary cost of the bondsman’s toil, to paraphrase Lincoln’s second inaugural. Certainly there’s something to that, however it was not always held to be so, and Melville’s poems are one way to remind ourselves of that fact.

Clarel is definitely on my list to read: if the Cantos project goes well I think I’d like to go through it with you all. It’s very long and supposedly quite involved theologically. Melville seems to have been in a kind of three-way impasse between the Dutch calvinism of his mother, a modern atheism of the sort increasingly common during the nineteenth century, and a kind of raging-at-the heavens gnostic rejection of this world and it’s maker as evil that feels very familiar.1 He seems to have been torn between these, unable ultimately to settle on one or the other, hence the tone of bitterness, sadness and defeat which characterizes some of his late work.

Maybe my favorite piece of Melville’s poetry is quite late, collected in Timoleon and published in 1891, the year of the author’s death. Entitled “Fragments of a Lost Gnostic Poem of the 12th Century” I’ve already written about it in passing once here.

Found a family, build a state,

The pledged event is still the same:

Matter in end will never abate

His ancient brutal claim.

Indolence is heaven’s ally here,

And energy the child of hell:

The Good Man pouring from his pitcher clear

But brims the poisoned well.

One hears here the voice of a parent who has buried a child, a voice proclaiming all is vanity, an extreme version of the thought that runs from Hawthorne down into the postwar liberals that action itself is somehow evil, that perhaps only stillness is or can be good. In those there is usually a sense that the observation of beautiful things is redemptive, is not without its flaws but still the best way to avoid breaking anything. For Melville, at least in this poem, there is no such redemption because matter itself is suspect, life itself a prison. The whaleboat was not far enough.

Aphorisms on American studies

I’ve got about five essays in the oven, same as it ever was. The theme uniting all of them is American culture. That which was, that is, that might be. I am drawn to the idea that there was something to the American culture of the postwar years, synthetic though it was, and that pulling it apart as both left and right did from the 1960s on was a mistake. It was a flawed republic, monstrous in many ways, but it accomplished much.

Perhaps the polity that had as its tutelary geniuses Walt Whitman and Herman Melville could never hope to endure.

Time creates so-called organic culture, dust and sedimentation producing the appearance of unity and naturalness. When the bones are on the surface as they are in the United States, one perceives a monstrous synthetic quality which is really present at the root in all others. All culture is willed, the question is one of consciousness.

Myths are necessary but must be held in a middle place, neither discredited nor held as religious dogma. We have done both and are so much the worse for it.

Ours is an adolescent culture burdened with self consciousness.

And all your rage and glory: thoughts on Bob Dylan

Last week

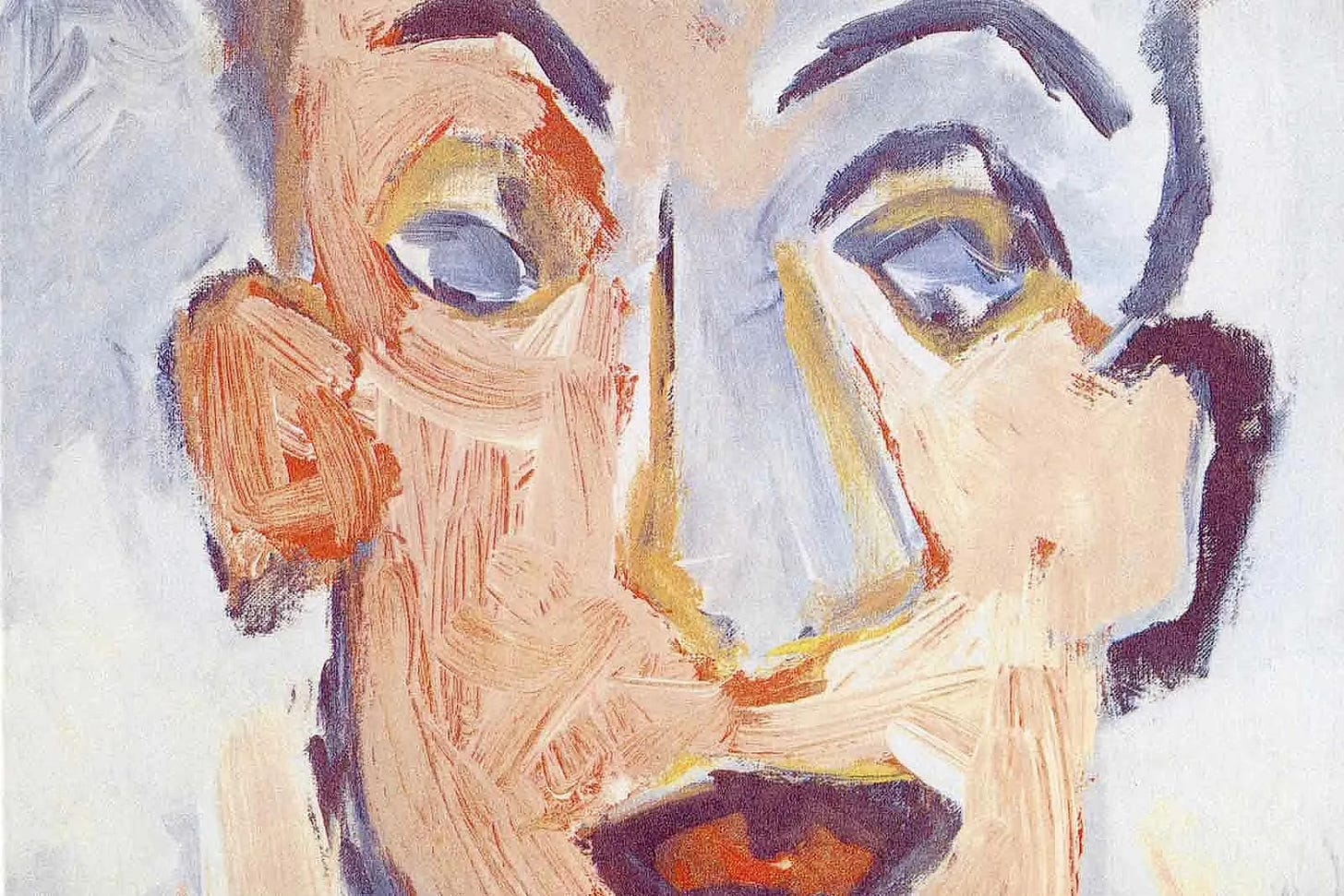

asked me if I was a Bob Dylan fan, which is for me a somewhat complicated question. Basically the answer is yes* but the *is doing some heavy lifting. Dylan is an extremely uneven artist, someone I can't imagine loving all of the way you can love, say The Beatles. The best periods of Dylan are to be clear some of the greatest American music ever made. A record collrction which does not have the run from Another Side of Bob Dylan through Blonde on Blonde is not a record collection in my book. I will grant even that the period from 1967-74, regarded by the first generation of Dylan enthusiasts as fallow and confusing years, itself contains some of the most rewarding and downright enjoyable albums of his career. I'm a particular fan of John Wesley Harding and New Morning. I will even to a certain degree go to bat for his christian records, which get a lot of unwarranted hate from a certain type of smug atheist bohemian, even if I'll admit at the same time that Saved isn't that good, and really only Slow Train Coming is on the same level as his best work of the 1970s.There is something in the great American artists which trains to escape from themselves, from this country and this world. Dylan is a little muted on this count-he might've sung about Captain Arab, but he's not interested in the whaleboat, and that particular track ends with Dylan sailing right back the way he came. He has a way of running from his genius, or perhaps is led by it into strangeness: Dylan has a way of perpetually changing without actually ever leaving the small plot of land he’s been tilling since the late 60s. I would be interested to get

or John Pistelli’s take on this, but the canonical 20th century literary figure Dylan reminds me of is D.H. Lawrence: not even an American, except perhaps in spirit. American at all, except perhaps in spirit. In both artists there is in my view at least a lot of dross, but the best work is epochal, must be apprehended, etc.Really it's mostly the 1980s stuff which is really dubious-an uneveness sets in on the second side of Desire and doesn't leave for the next twenty years or so, with some exceptions. Slow Train and Oh Mercy are classic albums, Unplugged is a pretty good listen. Something in the way he sang between Street Legal and Time Out of Mind gets on my nerves. After that, though.... Dylan's 2lst century comeback is a remarkable thing, the run of record between Time and The Tempest a remarkable fourth or so act, followed by another (!) period of self-obfuscation2 in truly incredible style, albums of Great American songbook tracks which you really only need to hear the once, and that's even if you love the songbook as I do. To then come out of all that with a sixteen minute dirge about JFK in the middle of COVID-that's a truly great artist right there. I do love Dylan, but it's a qualified sort of love. There’s something remarkable about the fact that the most recent occasion for someone else to have a hit with a Dylan song was in 2010. Anyway, whatever I think about the rest of it, Blonde on Blonde is as Bloom (Harold) put it, part of the American Sublime.

I sometimes think that one has to have felt that rage at the Almighty, that impotent wailing into the heavens at that which may be uncaring and malicious or merely nonexistent to truly understand Melville. Conversely if one is of the opinion that such a mood is a fundamentally immature and stunted attitude and one must learn simply to put one’s head down and admire the world as it is, he is less appealing. I find it sort of fascinating that the postwar liberals loved Moby Dick and Billy Budd so much, but they probably saw different things in him than I do.

Or not-like Lynch I think Dylan is generally more sincere than people take him to be. I don't necessarily think Self-Portrait was supposed to be bad, I think he just figured that Elvis and country guys got to make that kind of middle of the road record, so why couldn't he? On the other hand I absolutely do think there was a certain calculatedness to the shift after Blonde on Blonde.

Melville's crisis in faith reminds me of some of today's dynamics though in a more secular form

FWIW I have recently bought the Bootleg Series releases Trouble No More and Springtime in New York, covering Slow Train… through to Empire Burlesque. Having spent all my life deriding that period of his work, I find myself now revelling in it. (As represented on these two records, anyway. I’ve no desire to buy any of the original albums.)