Hi! Just as a heads up, while I don’t discuss the plot of the book that much in the following review, it is nonetheless extremely spoiler heavy, so read ahead at your own risk unless you (like myself) really don’t care about such things!

It could perhaps be argues that the act of placing the word "Major" in the title of

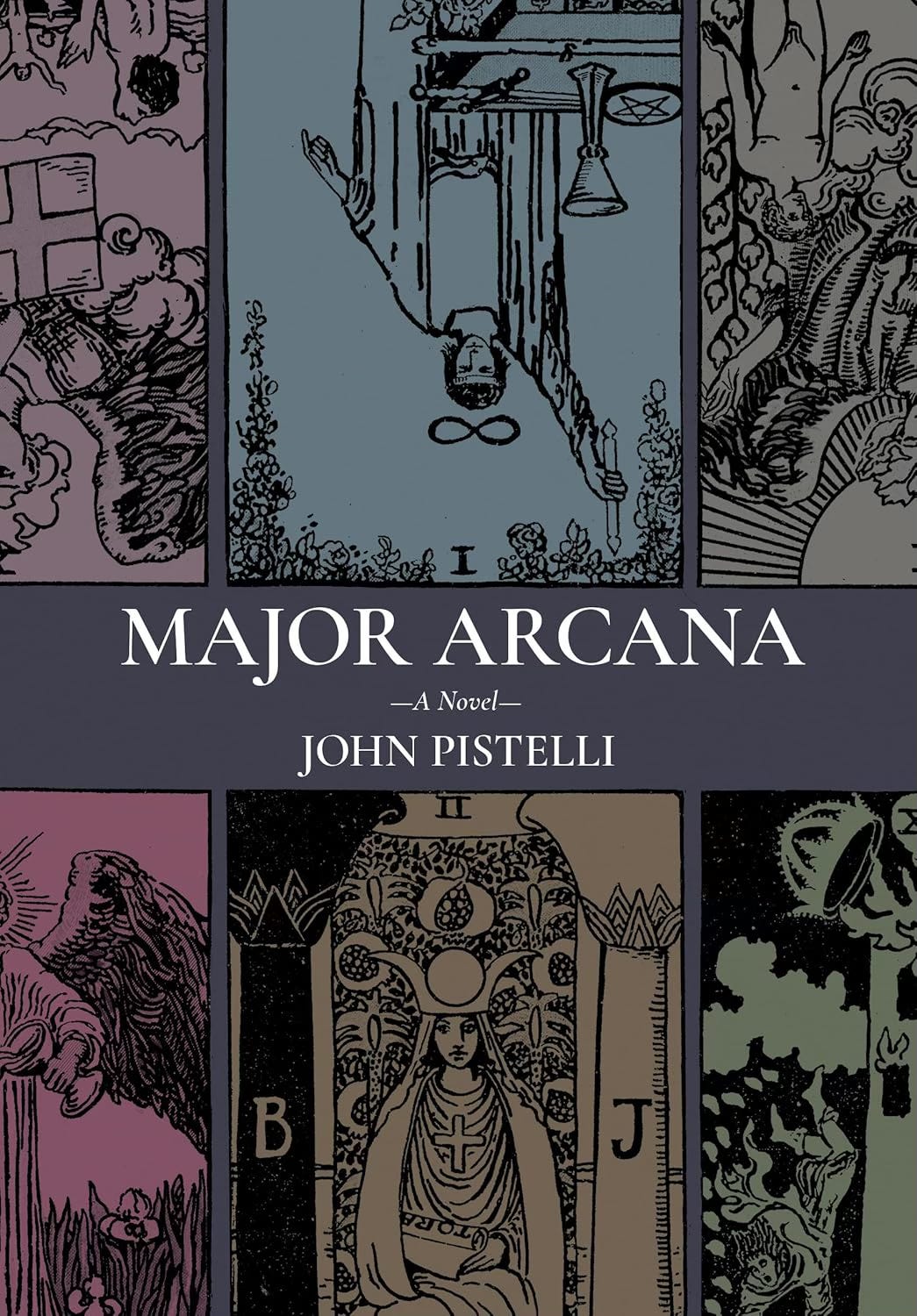

’s fourth novel is an act of manifestation of the sort that his nonbinary-ish influencer protagonist would encourage from her online viewers, but the fact remains that Major Arcana is a significant step up from his earlier fictions, and one of the most exciting books of 2025 thus far. Serialized on the author's substack and briefly self published in 2024 before it was picked up by Belt publishing, MA follows a group of around eight characters, 4 gen Xers, one millenial, and two zoomers across several decades as the novel works backward in a style somewhat indebted to the works of Toni Morrison and Don DeLillo, to explain the suicide on the campus of a thinly-disguised University of Pittsburgh that opens the narrative. This ensemble cast surrounds the convergence of the disgraced Bronze Age comic book writer Simon Magnus and the quasi gnostic manifestation influencer Ash del Greco. Because I will be somewhat focused on politics, philosophy, and the minutiae of the influence of various 1980s British comic book writers, a few compliments should be paid to the novel to start out: Pistelli writes the internet very well, better than most writers his age and frankly than many of those contemporary with Major Arcana’s zoomer protagonists. In contrast to many contemporary writers he has a particularly zany sense of plot, preferring absurd near-science fiction and magical realist adventures to the rather solipsistic efforts of this or that composer of autofiction.The early sections of the novel, which follow Bronze age of comics wunderkind Simon Magnus in Simon Magnus's exile as a gender-abolitionist/satirist professor of comic book studies under internal investigation for the influence of his 1980s and 90s works on the whose zoomer youth whose aforementioned suicide is thought to be related to his pop cultural daring, and are suitably humorous, somewhat mean-spirited satire very much in the mold of an anti-PC campus novel such as Roth’s The Human Stain.

Two Shakespeare scholars who had been mortal enemies for 40 years and who both refused to retire—a withered octogenarian New Critic in a rumpled brown suit (author of The Art Itself Is Nature: Tension and Reconciliation in Shakespeare’s Late Romances) and a sexagenarian second-wave lesbian separatist feminist with the tips of her chopped hair dyed purple (who had written My Foot My Tutor: Shakespearean Images of Sex-Class Subordination)—vehemently protested. In a shaky voice, the old man grumbled about clarity in communication; a colleague who had apprenticed in deconstructionism in the 1980s, and who’d authored (De)Facing It: Conrad’s Allegories of Inscription, reminded him that ambiguity and aporia were the essence of the literary. The feminist more forcefully, albeit in a longtime smoker’s rasp, expressed her resentment at receiving this high-handed lecture on gender from a man, but, after all, Simon Magnus was not a man, which was the whole point of this conversation, as the younger faculty protested.

One of the central themes of the work, treated in full-blown red meat, “damn kids with their pronouns these days” style here through Magnus’s disillusioned and middle aged eyes, but mercifully with a much greater level of of nuance in the subsequent chapters of the book, is the unanticipated influence of comic books such as those written by Alan Moore and Grant Morrison (more on them later) as their avant-garde elements were assimilated into the culture over time.

The political sensibility of Pistelli's fictions is probably best captured not so much in Major Arcana itself, but in his novella Right Between the Eyes. One encounters there a nostalgia for that old time religion (Catholicism or Stalinism) and its Law, and a deep contempt for soft-headed bien pensant liberal/left rejections of those almighty dictates, coupled nonetheless with an unwillingness or inability to actually live by those creeds. In a generational conflict, his sympathy is generally with the parents, and the chapter dedicated to Jessica Morrow, the mother of Ash Del Greco’s self-annihilated chaste paramour is one of the most moving segments of the novel.

She did see a meme in the feed one day, however—the day after Jakey’s funeral, in fact. Though she’d guessed that it had been meant as a dark joke, like most memes she ran into, commiseration in shared suffering and a shared laugh from some despairing boy in some suburban basement who couldn’t get laid. (Is that why Jakey had despaired? No, he was surely too young, or had been too young, young or old as he’d ever be, to have worried about that.) Instead of giving her a grim chuckle at the often unspoken truth, however, this meme so succinctly—but also so strangely and so beautifully—expressed what she thought of as her dilemma that she, who had not cried at her son’s viewing or his funeral, began to shake and sob right there behind the counter, beneath the encyclopedia set, in her mercifully empty shop.

The meme showed a little blonde girl, five or six years old. She looked dutifully into the camera, squinting or wincing more than she was smiling, a look more of apprehension than childish wonder.

Above an expanse of grass behind the girl reared the old skyline of the big city Jessica Morrow somehow thought, even now, that she would eventually somehow run away to, the skyline as it had been for the whole last quarter of the last century, commanded by those two columns, those giant bars of glass challenging the sky, proclaiming the dominion of man, of commerce, of America, for better and for worse, over the face of the earth.

The sky was clear but somehow ominous—probably the meme artist had, with some digital tool or other, exercised poetic license—not quite blue as a clear calm sky is blue, like the sky that Tuesday morning over two decades ago had been, but storm-darkened halfway to an electric indigo.

The color reminded her of when a pleasant dream slowly curdles to a night-mare. You’re in the car with your father; you’re on your way to a party; it’s a sunny day. Then it’s not sunny anymore; he turns his eyes from the road to face you; those black marbles aren’t his eyes; that man is not your father; a party, you somehow understand, is certainly not where you’re going. In this purple, unnatural monsoon sky above the girl and the Towers, the meme artist had added, in a typewriter font evocative of the middle 20th century, the slogan: The world you were raised to survive in no longer exists. Whatever it meant exactly—whatever political message the mememeister had intended—Jessica Morrow thought it described her problem exactly. She could have been that girl on that day. Over a long weekend when she was a girl, her mother had taken her on a Greyhound to the big city shortly after her father left. They’d shopped and dined and gone to museums; they’s gotten dressed up and gone to see Miss Saigon. How could it be that she was 38 and had already lost so much? She wasn’t raised to live in a world where her young and only child died long before she did (“long before she did”? when had she died?), and by his own youthful hand, his hand just barely full grown and beginning to sprout a bit of dark hair at the knuckles like his father, not the babyish blonde fuzz, the memory of which doubled her over.

On the other hand the gendered explorations of the novel’s characters are treated with a great deal of delicacy and sympathy, even when they may at first appear satirical or somewhat flippant. Simon Magnus’s disavowal of pronouns is an example of this-it may have originated in an effort to outdo Simon Magnus’s annoyingly woke students, but Simon Magnus’s history as revealed throughout the book offers a much more nuanced and complex view of the subject, and at several points throughout the book transgender characters are treated with a sympathy that helps to mute some of the more brutal satire.1

As mentioned earlier, Simon Magnus is clearly based on the great comic writers of the dark age era "British invasion" of American superhero comics. This fact winds up being slightly obscured by his origin in the provincial New England forests, but the inspiration is nonetheless there. The gender exploration and the ritual magick is pure Grant Morrison, while the fixation on rape and birth and the form of the work Simon Magnus produces with Marco Cohen is much more reminiscent of Moore's 1980s and 90s work, and the Wagnerian Sturm und Drang of a Watchmen or From Hell. Overman 3000 is a *very* Moorite work, borrowing liberally from Watchmen, Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow, and Swamp Thing, and Moore's run (and Gaiman's continuation) of Marvelman. The text itself is somewhat torn between these two masters of the form, at once rejecting and ambivalent and claiming each one in its own way. There is a certain reluctance on the part of the author to name Morrison but this is I think for some of the same reasons that when

asked if I was a Moorite or a Morrisonian the other day I wasn't sure how to answer him. There is something in Moore's Wagnerian affect that I am not fond of, a godlike remoteness from the human world in the routine partition of his clockwork grid and portentous dialogue. In many moods I prefer Morrison's lighter, defter touch, more attuned to the conditions of late modernity and the moods of a Gen-X,Y,or Zillenial. On the other hand Morrison tends at their worst toward a kind of glib nihilism, not even quite sure just what it is they are trading away with their quips and references to late 20th century British pop culture. Pistelli's extratextual discussion of his influence on his blog and in interviews has, it seems to me, displayed a somewhat bad faith disavowal of the influence of Morrison on the text, something that think I understand quite well.Grant Morrison's work following that glorious first decade and change has tended toward a certain fannish company-man quality that doesn't mean they haven't written a few more classics-All Star Superman and about half their Batman run are worth your time-but it does leave Morrison deeply implicated in the general “adult child”-ization of American and to some extent global culture in the 21st century that both Pistelli and myself are opposed to.2 The crucial predecessor to MA is perhaps not any one of his previous novels, perhaps not even the surreal tragicomedy Portraits & Ashes, which touches on some of the same themes of modern art, online life, and the gendered styles of the modern age. No, the crucial precursor is a 2017 review of Morrison's Doom Patrol in which comparing Morrison to Bolshevik revolutionaries and the whole sick crew of the pre WWI avant-garde, drawing on Boris Groys' argument that the bolsheviks merely instantiated the visions of those artists, he quotes from a speech Morrison gave in 2000:

Let’s go in there and give them something they cannot digest. Something they cannot process. Something so toxic, so dangerous, so powerful…that it will breed, and destroy them utterly. Not destroy them—turn them into us. Because that’s what we want. We want everybody to be cool.

The review is clearly ambivalent about these ambitions.

Like Morrison—like Breton and Marinetti—Caulder wants everyone to be cool, and it makes him a murderous villain. Doom Patrol, then, is more ambivalent about is own vision than it appears at first; it is honest about the trauma and the coercion that underlie its liberatory values at the other end of the avant-garde century.3 That vision and those values triumph at the conclusion, though, when the trans street Danny becomes a world (no fear of a queer planet here) and Kay Challis is reclaimed at the end for the heroism of saving weirdness.

Major Arcana is a deeply Morrisonian text even as the text within within a text belongs very clearly to Alan Moore's influence, and it is moreover a Morrisonian text which seeks to work a kind of countermagick on Morrison's vision at its most threatening. The second half of The Invisibles in which the characters realize that their archonic enemies are the other side of the same coin and largely forgo violence in favor of a more pacifistic cultural preparation for the apocalyptic enlightenment to come is an obvious influence here, as are the good parts of New X-Men.

At an earlier stage in my thinking about this book I would have made more of the resolution, the cessation of outward gender exploration, the return of Simon Magnus to the heterosexual normativity which had evaded or been driven away by Simon Magnus and Simon Magnus’s art, the conjoining of petit-bourgeois commerce and maternity in what would be nearly a neat victorian resolution were it not for the cross dressing and suicide and the magick. On reflection however, I am not sure that I possess the sort of political-aesthetic convictions which would enable me to make a firm critique in this department. It is I think somewhat a book of its specific place in time-as the author confirmed in several places recently, late 2023-and the hopes of that moment amongst a particular group of people, but the best art has a way of escaping from our historicism, and I look forward to rereading Major Arcana someday to discover what it becomes to me over the years. 4/5

I remain on revisiting the book for this review largely unsure of what to make of Ash Del Greco’s ex-friend Ari Alterhaus, who is structurally necessary for Ash del Greco’s development as irl manifester (and her (?) arc through the novel from disability-extremist genderqueer gender nullificationist to online tradcath detransitioner a la dimes square is very funny) but is nonetheless the closest the novel comes to feeling like something out of one of Matt Walsh’s fever dreams.

He probably wouldn’t particularly care for this comparison, but something in Pistelli’s dialogue reminds me somewhat of the early works of Kevin Smith: the subjects under discussion is certainly different, but there is the same odd, over-sophisticated dialogue, which in either case I appreciate, but nonetheless somewhat punctures the verisimilitude of the work. Do real people who aren’t career academics or graduate students really speak this way to one another? Still, it’s a very minor criticism.

Crucially, and this may be wrong, but I went through and counted, Morrison is never gendered in this review.

I'm committed to getting through Morrison's Luda right now and I'll also read this one, but I'm not sure I like any of the tradition... just following through on a grim exposure project I started with Palahniuk as a teenager, wary of taking my eye off the trends in viscerally subversive irony. "This is what the worst guys at the parties will be expecting to be able to use to cleverly throw you off your stride, so be ready."

I am not reading this review until I’m done with the book. I don’t want any spoilers. I’m liking the way it’s developing, and I don’t want to have it ruined.