Hi! I put this out last year, got disillusioned with my efforts in reviewing books and deleted, and then decided it was pretty good after all, so here it is again. In my view this goes without saying, but some people do care deeply about such things, so: this review contains all kinds of spoilers for this 1956 novel.

I am somewhat of a partisan for John Barth.1 His first three novels were enormously important for me as a writer and dare I say even as a developing human being, and yet for a variety of reasons Barth is an obscure figure today, one of the last living (at the time of writing in 2023) representatives of perhaps the greatest generation of American writers. I’ll extrapolate a bit on why I think think this is as we go along in the oeuvre, but for now let’s examine his first novel The Floating Opera.

the hardest thing about the task at hand-viz., the explanation of a day in 1937 when I changed my mind-is getting into it. I’ve never tried my hand at this sort of thing before, but I know that enough about myself to realize that once the ice is broken the pages will flow all too easily, for I’m not naturally a reticent fellow, and the problem then will be to stick to the story and finally to shut myself up.

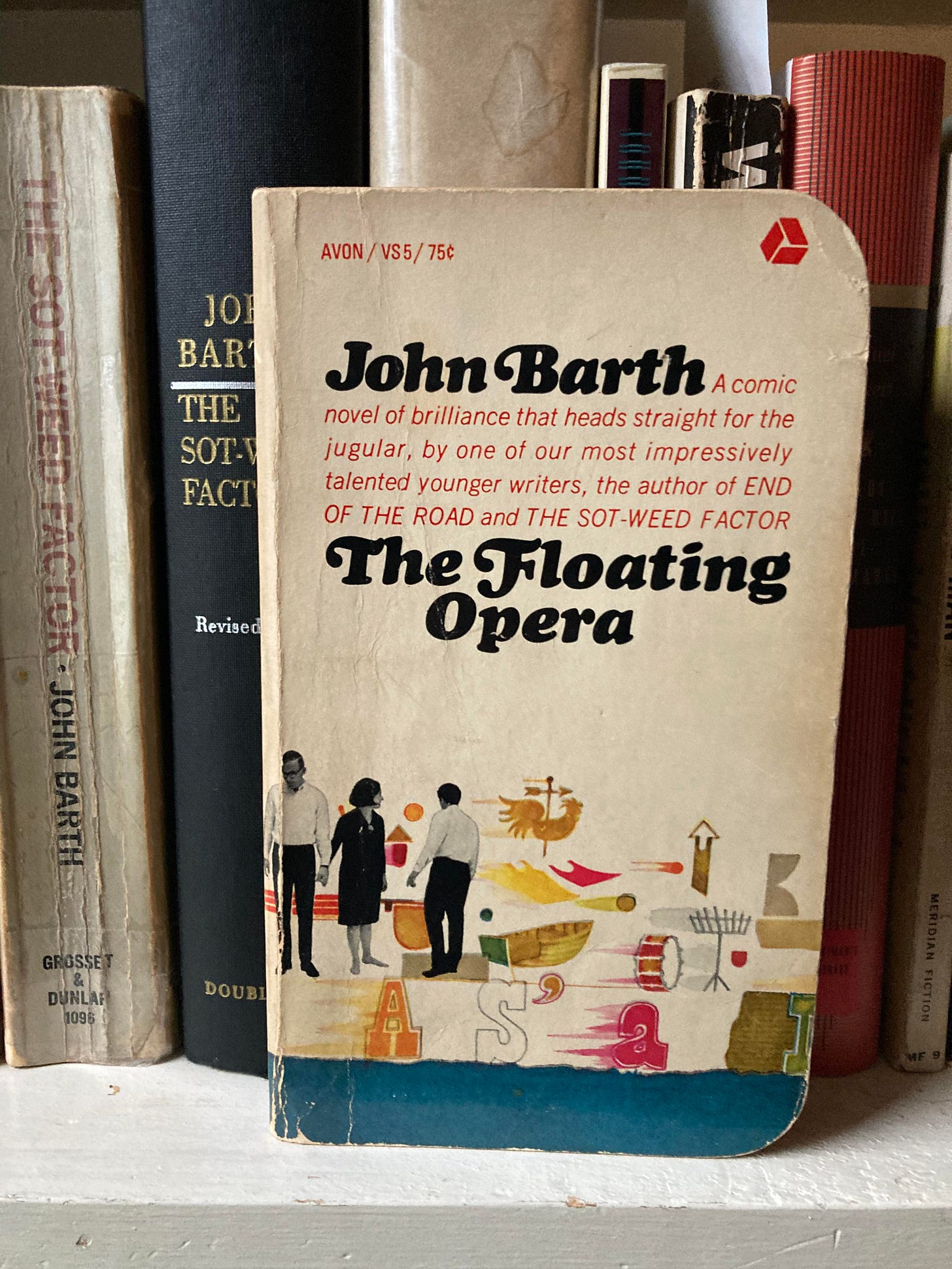

Published in 1956 in a redacted form and rereleased in the longer, unexpurgated edition ten years later after Barth scored an unexpected hit with Giles Goat-Boy, The Floating Opera recounts in a discursive, disjointed fashion how successful Maryland lawyer Todd Andrews decides to kill himself one June day in 1937 and then changes his mind later that night. Along the way we are thrust repeatedly backward in time to Todd’s early life, his service in the first World War, the strange love triangle of sanctioned cuckoldry between himself and married friends Harrison and Jane Mack, and the suicide of his own father during the Wall St. crash of 1929. All of this is narrated by Todd himself in what he calls his “Inquiry” a vast philosophical examination aimed at explaining his father’s death.2

Everything, I’m afraid, is significant, and nothing is finally important.

The structure of The Floating Opera is formally ambitious, combining sustained narrative digressions in the vein of Lawrence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy with interpolations of advertising a la the newsroom segment of Ulysses and even most of a chapter written as two discrete columns on either side of the page. All of this is handled however with such care and in such a down-to-earth manner that on my first reading I barely even registered them as such. It’s a very approachable-seeming novel, which is a funny thing to say about a book that hinges on an adulterous love triangle and a suicidal lawyer discussing at some length his worldview and the absurdities of the case he’s arguing for the man he’s cuckolding. This quality extends to the philosophy of the book: a kind of mid-Atlantic spin on French existentialism a la Sartre and especially Camus, whose thesis in The Myth of Sisyphus the book consciously or unconsciously echoes.3

Unless a man subscribes to some religion that doesn’t allow it, the question of whether or not to commit suicide is the first question he has to answer before he can work things out for himself. This applies only to people who want to live rationally of course. Most people never realize that there’s a question in the first place, and I don’t see any particular reason why they should have it pointed out to them.

The resolution to Barth’s plot, in which Todd realizes (after failing to kill himself and nearly every other character in the book by blowing up the titular floating opera) that if nothing has any absolute value suicide doesn’t make any more sense than continuing to live- then seems to gently poke fun at Camus’ rather gothic European philosophizing. When I first read the book this seemed enormously significant to me, and maybe it still does: we’re Americans after all! Why should we unquestioningly take on the existentialists with their vistas of burning cities and total exhaustion, and if we must, let’s put our own spin on it!4

It’s strange how much a book can change between readings. I was in an unsettled state of mind when The Floating Opera came into my life: myself existentially troubled and unknowingly near the end of a phase. It was one of those moments of absolutely sublime depression in which very little is funny, and what is shines like the sun. On first reading there seemed to be a terrible weight to the nightmarelike homoerotic sequence of Todd kissing the German sergeant in the shellhole or his discovery of his father’s corpse hanging from the basement rafters that has mostly vanished on my revisiting the novel for this review.5 The darkness is mostly still present-the sequence of Todd cutting down his father’s body is chilling and as mentioned the full 1967 text of the book climaxes in an attempted mass-murder/suicide aboard an entertainment barge-but it doesn’t stand out nearly as much to me now. That’s not even getting into the fact that I was reading the bowdlerized original edition of the book in a 1960s paperback with the strangest corners I’ve ever seen on a piece of adult fiction.

Something that emerged over the course of the reread, although I’d noticed it with some of Barth’s subsequent novels is that there really is no expansive worldview here aside from the existentialism. Of the major American postmodern novelists of his era Barth is the one most easily written off as a nihilist trickster: he wasn’t a virtuoso prose stylist like DeLillo could be, a prophet on the hill bemoaning the state of things like Gaddis, or a pot-smoking sage illustrating the satanic machinery under the skin of the world the way Pynchon sometimes was. With John Barth you just have the story and the sense that the storyteller is enjoying himself magnificently in the telling, which is fine by me but there are various valid objections, and I’ll point out some of them as we go along. He’s a writer’s writer not in the usual sense of “how do they do that??” but in the more positive sense of “I could do that” and all the freedom that entails.6 Eventually I think he does find a deeper purpose for his fiction, but it’s a trick he only pulls once or twice, and I don’t always find his answer entirely satisfying.

Alone in my room then, I sat on the window sill and smoked a cigar for several minutes, regarding the cooling night, the traffic light below, the dark graveyard of Christ Episcopal Church across the corner, and the black expanse of the sky, the blacker as the stars were blotted out by storm clouds. Sheet lightning flickered over the post office and behind the church steeple, and an occasional rumbling signaled the approach of the squall out over the Chesapeake. How like ponderous nature, so dramatically to change the weather when I had so delicately changed my mind! I remembered my evening’s notes, and going to them presently, added a parenthesis to the fifth proposition:

V. There’s no final reason for living (or for suicide).

All in all The Floating Opera is an accomplished debut, not a masterpiece but a fine piece of work that establishes its author’s voice and style from the first page. It’s not a perfect novel-Barth doesn’t really breathe life into any of the characters beside Todd, who presents us the supporting cast almost as puppets for his own consciousness to collide with-and it must be said that some things about the book have aged poorly.7 That being said though, it’s a thrilling performance and well worth your time, and maybe more importantly to me at least, it’s partly to blame for my own efforts toward writing a digressive novel. Oops!

At least the early Barth; I never did finish Giles Goat-Boy, and while I enjoyed Lost in the Funhouse I could also see why David Foster Wallace thought that with it Barth had essentially ruined the literary novel as a form. I’ve always thought this was odd- if we’re to blame anyone for that it really should be those two Irish magisters of the maximalist and minimalist, Joyce and Beckett-but then Barth himself might suggest that literature has always been so, and it was realism that was the anomaly all along!

As befits the discursive structure there’s a lot more going on in the book than I’m letting on including multiple sexual escapades, a senior-citizen’s club meeting argument about the virtues of aging, and an extended digression about a court case hinging on a deceased pickle millionaire’s preserved stools being used as fertilizer for zinnias.

I remember reading somewhere that Barth claimed he hadn’t read Camus until after he wrote TFO, but I haven’t been able to find where I read it, so I throw up my hands and consign this observation to a footnote!

Barth did so more explicitly in the End of the Road, which I regrettably may have to revisit Being and Nothingness in order to review.

I will note however that it’s a much funnier book on reread than it was the first time. This may be due to frame of mind or a more leisurely pace of reading, I’m not sure.

Which ultimately may be a “mileage may vary” situation: as I said a few footnotes ago DFW seemingly interpreted “you can write this way” as “you must write this way” and while I enjoy his work more than some, much of what I find annoying in him issues out of this sense of being imprisoned in a metafictional logic trap, which as we’ll see when I get to Lost in the Funhouse is something Barth can probably be blamed for.

We’re all adults here, and I’ve raved about the book and its author thus far, but it has to be said that Barth really does have a sexism problem. He’s not hateful about it, but he nevertheless has a tendency (typical in some ways of male novelists of his generation) to write women as mostly empty vessels for male desire and will. More on that when we get to The End of the Road. Jane avoids that to some extent here largely because Todd perceives her as almost sharing a consciousness with her husband

They should, it occurred to me, be permanently locked together, like the doubler crab or Plato’s protohumans.

but there’s still a bit of it going on and it (along with the period-specific and plot-appropriate but still shudder-inducing minstrel sequence in the climax) definitely stands out to me. I’m not the sort to ding a book for this sort of thing unless it’s really egregious, but if you are you might want to deduct a point or two from the rating.

This is a really compelling review. I've had "The Sot-Weed Factor" on my list for years, but now I'm thinking I should consider reading some earlier Barth first.