Grant Morrison, The Invisibles, & 21st century neoteny

anarchic creative androgynous mass of references and signification

Hi again! This is yet another revision of something from a newsletter-this time maybe my favorite early mini essay coupled with a synthesis of all the times I’ve talked about Grant Morrison. Having actually finished The Invisibles I’ve included something a little more (still not that much though) like a straightforward review as well. Enjoy!

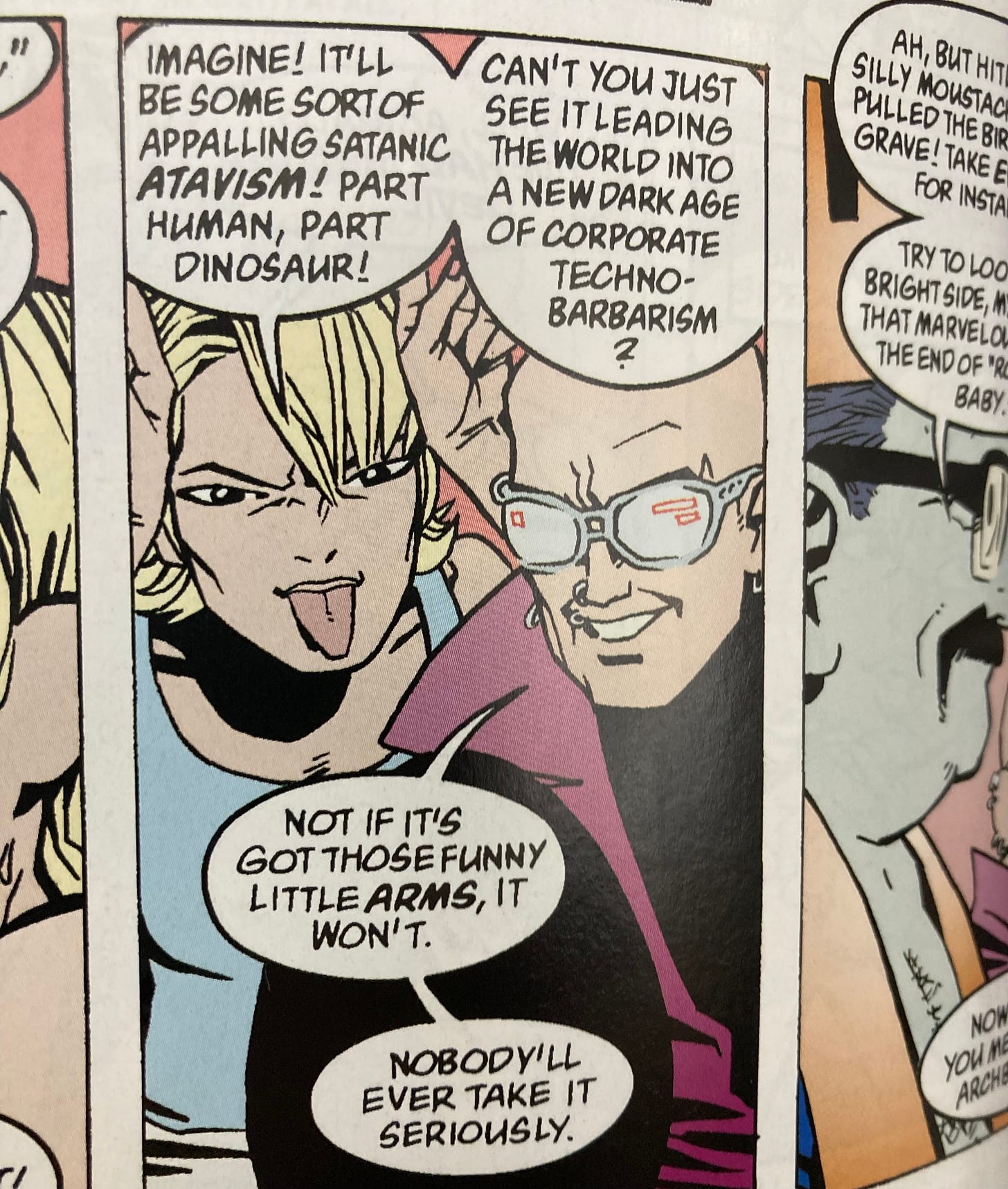

Over the summer I read Grant Morrison’s celebrated comic of the 90’s The Invisibles on my long, slow journey through their oeuvre. It’s hard to judge a catalog that one hasn’t actually finished yet, but it’s still handily the best I’ve yet read from Morrison- Animal Man is a fun pomo romp, Doom Patrol has a lot of fun zaniness but also a somewhat queasy “look at these freaks go! Aren’t they just adorable in their abjection?” undercurrent, while Arkham Asylum: Serious House on Serious Earth presents a fleeting sketch of a masterful and darkly symbolic take on Batman in which the Dark Knight is a figure of near-hysterical repression who must be reborn in the crucible of the titular madhouse.1 The Invisibles is a remarkable comic: in many ways prescient of cultural developments of the last decade or so, perhaps in different ways to different wings of the omnipresent anglophone culture war.2 Chronicling the story of a group of psychic terrorists picking up their newest member-a budding messiah from Liverpool-and their journey of enlightenment up to the apocalypse in 2012, it’s one of those rare pieces of media that is exquisitely of its moment but has held up remarkably well-which is something seeing as I felt like the whole thing demanded a soundtrack of Blur and Aphex twin.

Both Gnostic and deeply anti-Gnostic, the comic in toto is a fascinating meditation on rebellion and repression as two sides of the same coin, reaching an appropriately subdued crescendo in its final pages featuring a benign, transcendent apocalypse of the sort we’ve mostly lost the capability to imagine after the atom bombs and the decline of mass religiosity. Morrison is I think right here both to question rebellion and postulate its ultimate necessity for life and culture. This is always for me the problem with both political conservatism/reaction and orthodox religion: neither quite recognizes the oppositional romantic need of the human spirit in modernity.3 Every revolutionary from Christ to Marx, from Mani to Grant Morrison eventually becomes the black iron prison, becomes what one self-defines against. How to maintain the exquisite tension that produces greatness? I don’t pretend to have the answer, and neither I think does Morrison, although they try. I don’t think they’ve always succeeded: in fact they often wind up way out there either on one side (a lot of Doom Patrol, as much as I do love it) or the other (some of his 21st century work as a writer for DC4) but they recognizes the problem and they’ve tried to work with it, which is something a lot of frankly better writers fail to do.

I’ve had an intuition for a while- one admittedly borrowed in part from Elizabeth Sandifer and John Pistelli among others-that Grant Morrison is one of the unwitting prophet-architects of our century, just as truly as Wilde and Joyce were for the twentieth. So much of what they describe in those early works has become reality in strange ways, some predictable, some otherwise.5 The ideal Morrison semi-directly sets forth in the middle and ending sections of The Invisibles- of counterculture in collusion with capital against the powers of the earth to shape the world has been a disaster for both parties and has produced some unpredictable and less than desirable results. Surely all that chaos Magick was working to manifest something other than a Thiel check deposited into Anna and Dasha’s bank accounts? More aesthetically the pop-postmodern patchwork, cut-up system of reference weaving between high low, middle and period is now so ubiquitous as a model for culture and thinking thereof that it almost doesn’t bear mention.

It’s that broader sensibility that I’m concerned with, one shared as well by many of the other creatives associated with DC’s now-defunct Vertigo imprint (Neil Gaiman in particular, at least in the Sandman.) Many of these works have a certain crazy-quilt quality, dense with allusions and meanings, almost providing the reader with a self-contained canon of their own extending out and behind. Marcel Duchamp, William Shakespeare, Pablo Picasso, John Lennon, Z Cars, The Marquis de Sade and Percy Bysshe Shelley are all contained in either Doom Patrol, The Sandman, or The Invisibles, which is to say nothing of the various then-contemporary references that populate all those comics. It’s a veritable smorgasbord of meaning available to the younger reader as essentially a reading list, and I’m sure many fans of Morrison and Gaiman did follow the aesthetic recommendations of their favorite comic books as they grew older and matured.6

But therein, as the bard says lies the rub. “Matured.” One of the curious things that happened as the sensibility that produced these wonderful, anarchic, creative comics became hegemonic was that you no longer had to mature at all-in fact in some ways it was actually discouraged! There is no longer any pressure, any perception of need to set aside childish things and become an adult, no impetus to follow the secret threads hidden so carefully for you in the beloved books and tv and games of your youth . Indeed, poptimism suggests that to attain a true adulthood is to set aside any ambitions and remain forever in that state of childlike, uncritical consumption. You can just keep watching Luke blow up the death star forever, while Morpheus will sub with Hob again and again throughout the decades on the pages of your yellowing graphic novels and your only Shakespeare will remain the time you snored through Othello in 9th grade. You will shun the Beatles as “male abuser core” because the received wisdom on facebook and Twitter says so. All of this admittedly is very old man yells at cloud, but I’m still fairly young and as queer as Grant Morrison, and I think this aesthetic neoteny is one of the great cultural problems of our time.

Because it’s not good to stay a child forever. It’s not healthy. The world is a big, scary place, and getting more so by the minute. Can we really imagine that we can evade the responsibility of being challenged by art? can we really imagine that ours is such a tranquil world that we may avoid the great works even of our own time, that we might for the rest of our lives consume only the equivalent of chicken tenders every lunch and dinner? Moreover to be a child forever is to be helpless forever, and to be helpless before the world is a terrible thing. This is a lot to be putting on poor old Grant, and I don’t want to make it sound like I blame them for all this, although their whole “winning the culture war by taking the boardrooms” thing probably accelerated the already inevitable process by which the anarchic creative androgynous became the thing behind the desk in the penthouse holding the purse strings and therefore itself “the man” to be rebelled against by upstarts who think it’s terribly clever to hold their grandparents’ racial and sexual politics.

Which is tragic, because outside the metropole, beyond the far-more hermetic than either realizes world of the bien-pensant and the metrocon much of the populace who needs things like The Invisibles or Doom Patrol is still there, still waiting. Conservatism is only the new punk rock if you live in a complete bubble, totally shielded from the reality of the world outside.7 Probably some of you do. I think with many of you that sections of the cultural left took a disastrous turn in the last decade, and as I’ve alluded above Morrison’s aesthetics certainly contributed, but within them is also a way out. Let the mass of references and signification have meaning again, read the books, watch the films, listen to the music. Let’s all be adults again.

I have at times irresponsibly speculated that part of the appeal of dragging Morrison (willingly admittedly) into the status of “queer icon” is a subconscious effort not to have to think about this undercurrent in their early works the way you’d have to under our current left-liberal system of values were we speaking of a straight cis white man’s output. I’m not bothered by this: I don’t think you can ever really get the discomfort out of gender or sex, but it is there, and it’d be slightly dishonest not to acknowledge it.

Morrison is of course definitively of the political left, but there is a Morrisonian branch of the right, which arguably peaked slightly under a decade ago. It’s mostly gone now, crushed by a culturally authoritarian turn that considers their gender and psychedelic explorations entartete kunst to be thrown on the fire with the rest of the radicals-and what’s left of it seems mostly content to play groupie to that great machinery of power, smirking and cataloging the untermenschen, noting the shape of the folds and what is to be done to contain the pollution from their perches in the demimonde-but it was for a brief time monstrously influential.

I’ll accept that it’s quite possible that as the trads allege, things were vastly different before-perhaps Reiff et al are correct that the long premodern centuries of orthodox Abrahamic monotheism truly were a fundamentally superior state in which we didn’t have this cultural-psychological need for our individual selves to be so affirmed. That being said we certainly do now, and I don’t think we can turn back this (or really any) clock.

I don’t dislike Morrison’s work on Batman or Superman: you just have to have a pretty strong grasp on the long term canon of the characters, which I sort of do, but all such efforts probably do suffer a bit-you even get a bit of this with New X-Men, although he does a bit of mean-spirited deconstruction of the Claremont era at the end that makes it a little more interesting-for being tied down to these extremely established characters with incredibly long histories.

This even extends to something like New X-Men: the obvious connection would be the sentinel plane crashing into Magneto’s tower on Genosha, but on reading the first few volumes recently I was struck by how much the portrayal of the U-men (transhumanist self-help cultists who graft unwillingly-harvested mutant body parts onto themselves) in the comic anticipates the utter disgust with which a certain sort of essentialist or reactionary gay or lesbian views trans people as mutilated, false simulacra trying to exterminate the Real Thing.

I’m rather pointedly excluding Alan Moore from this, because while he does draw from elsewhere as with Shakespeare in V for Vendetta, Moore often scans as being like Blake or Lawrence: a man writing his own myths that stand with the great work of the past rather than drawing on it for support.

This can be another entry in the little canon of “two things are true at once” we’ve been building over the last few weeks. The sensibility Morrison encodes is both hegemonic and still revolutionarily underground, likewise parochial conservatism is both perpetually on the back foot culturally and a suffocating miasma for those who can’t conform themselves to the ideal form of normality in the places it controls.

I really liked this. There were a LOT of dudes working the same lane as Morrison in the 90s-2010s and they were a real fixture of my teens and twenties. China Mieville, Michael Chabon, Patrick Rothfus, even Joss Whedon kind of falls into this category. Guys promising to “elevate” genre fiction, or add genre spices to their literature. I loved this stuff at the time even though I look back on it as kind of empty calories.

Looking back, I think what all those authors had in common is that they combined genre elements with “rewarding you for having an undergrads cultural competence” or “giving a cliffs notes version of Jung”. This made for a reliably entertaining reading experience- and a cliffs notes familiarity with real ideas is better than nothing. But it’s a poor substitute for the genuine article.

Great piece. Growing up in backwaters the Invisibles was my bible. We thought by going to raves we thought we were doing something important, something beyond youthful hedonism. Now it all seems so trite.