"It is true, that which I have revealed to you; there is no God, no universe, no human race, no earthly life, no heaven, no hell. It is all a dream—a grotesque and foolish dream. Nothing exists but you. And you are but a thought— a vagrant thought, a useless thought, a homeless thought, wandering forlorn among the empty eternities!"

Mark Twain, The Mysterious Stranger

When I was an undergraduate I took only two philosophy classes in the first and last years of my education. Both were surveys, really as I understand then now too brief an introduction to be anything but a very cursory glimpse into some intriguing area or other. The first was an asian philosophy intro, the second an introduction to nineteenth and twentieth century European existentialism. The first was pursued primarily out of the sense of aimless intellectual curiosity that guided my undergraduate education generally, but the second was inspired by personal experience. Beginning in my sophomore year and continuing intermittently ever since, I have been plagued by recurring nihilistic terrors, episodes of depression and despair which while never enduring have nonetheless walked behind me for now nearly the entirety of my adult life. This is why, as I’ve told

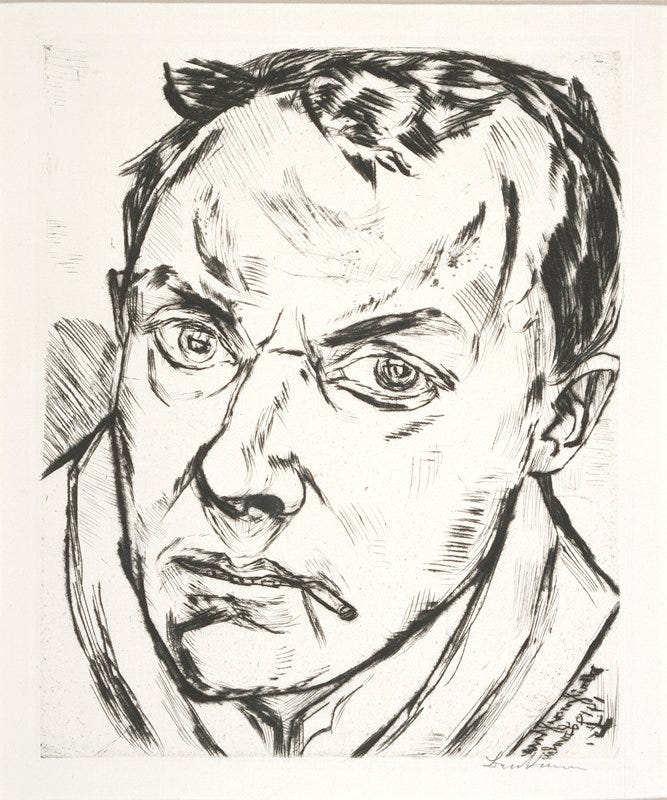

although I confess to finding his overall program and much of his output unserious, I’ve never been able to work up quite as much animosity toward Jordan Peterson as I am supposed to have. So much of his work seems to me geared toward a desperate striving to keep down that sinking feeling that nothing is, that all existence might be an errant, aimless thought without form or meaning-if that isn't itself anthropomorphizing the nothing a bit too much.It was interesting, given this background, to read Harry Neumann’s single book, the 1991 essay collection Liberalism. Neumann was born in 1930 in a German republic already in the midst of political crisis; as a child his family emigrated to the United States amongst the mass of. Earning a MA at the University of Chicago, where he was a student of Leo Strauss, and a PHD from Johns Hopkins, he went on to spend the majority of his career at Scripps college and Claremont Graduate University, where he co-taught a seminar course “Socrates or Nihilism” with Harry Jaffa for many years. Despite this connection, Neumann’s output is “Straussian” in a very eccentric way indeed, and his affiliation with Jaffa’s school is primarily honorary. Like Stanley Rosen, Neumann disagreed with Strauss on various points, but unlike Rosen, he was a nihilist who sided in certain ways with Nietzsche and Schopenhauer. Judging by the content of these essays he seems to have been particularly attentive to the critique of liberalism offered by l Carl Schmitt. In certain respects he could be said to side with the Nazi theorist of the state of exception in the famous exchange that is appended to the most common English translation of The Concept of the Political.

Philosophers are not liberals for honest liberalism rejects the illiberal core of both philosophy and politics, the faith in a non-arbitrary, eternal good or god. Philosophy's goal is apprehension of the good. Liberalism is radically unphilosophic precisely because it is radically apolitical or atheist. Political liberalism is the ridiculous mating of liberalism and politics or philosophy. It is the dishonest moralization or sanctification of liberalism's inherent nihilism. Strauss and Schmitt rightly insisted that political liberalism owes its amazing success to its amazingly successful dishonesty

Liberalism is a stimulating read, although it betrays its origin as an entry in that great intellectual genre of “essay collection masquerading as a book with a thesis”, frequently repeating the same anecdotes, the same argument, in a way that at times does seem somewhat gratuitous. In essence Neumann’s one argument, made in multiple ways throughout several essays, is that nihilism is correct, and liberalism deterministically produces nihilism. The latter argument is certainly present in Strauss’s works, but is usually lurking behind arguments about historicism and modern political philosophy-he was rarely this direct, and it can be debated to what extent he did believe it. Neumann is much more direct, and he offers by negation a fascinating look at the thinkers by whom he was shaped and with whom he engaged.

Only a discipline ruthlessly inculcated over centuries and millennia, in the face of reality's nothingness, creates the illusion that anything is something and not nothing. Pseudo-academics are repelled when reminded that this successful indoctrination into their bigotry is the meaning of their pride in their discipline and its claim to professionalism. On the other hand, they find it beneath them to embrace the old, fundamentalist faith which they imply and which consistent conservatives seek to conserve: Divine guidance would be required to save their lives from reality's nothingness.

Neumann's book is a helpful document in understanding the sort of Straussian type of which he was an honorary member. He may be a nihilist, but he retains the sense that once must either accept every inch of the Law in its glory and strictness, or else the abyss of nothingness as the only thing approaching truth, which is of course a fiction. Where in my view this leaves room for questioning and quibbling is the point that this binary opposition does, it seems to me, lead in some ways rather straightforwardly toward the sort of pseudo-nihilist desperation of which Neumann accuses Nietzsche & Heidegger, and which he cites Rudolph Hess and Andrei Bukharin as examples of. If nihilism is a difficult teaching, which Neumann thinks and I assent, then surely the prospect of such will be a motivation to accept this or that nonsense in a desperate effort to escape from nothingness???

There is something very European, and further very specifically German about this insistence that life must perfectly conform to a system, or even an absence thereof-a nothing.1 My own personal variant of American exceptionalism is believing that our characteristic Yankee stupidity exempts us from these European dooms and idealisms. I can’t remember if I’ve already quoted

’s recent Wisdom of Crowds essay in one of these, but if not, here goes again:To me, the characteristic American outlook is that there are no zero sum games and that there is a possible world in which everybody wins, an outlook that somehow co-exists with an embrace of competition and the marketplace. It is a country of optimistic comedians.

Neumann’s Germanness is most pronounced in the final essay of the collection, “Homage to Verdun.” This is the chapter which most sends a shiver down my spine. Elsewhere he is too true to his nihilism to seem as threatening as his chosen philosophy might otherwise make him seem.2 Neumann compellingly castigates Heidegger and Nietzsche for a certain failure to live the truth of their beliefs, for their desperate efforts to escape from the implications of the nothing they presupposed.

The fanatic because impossible will to will, this nothing desperately resolved to be more than nothing whatever the cost, also is responsible for the trivial contemporary fascination with technology (sciences) and creativity (humanities). Nauseated by this global hegemony of nihilist triviality, the rule of Nietzsche's "Last Man," Nietzsche and his only student, Heidegger, were driven to their desperate, ultimately impossible, final solutions or questions. However opposed these efforts are, both share the desperation inspired by the confrontation of man's moral-political passions with nihilism, the realization that those illiberal passions are as meaningless as everything else in reality's void.

In the Verdun essay however, there is an assertion that there was something noble, sublime in that combat, in the mutual slaughter of those million Frenchman and Germans by the Meuse in 1916.

Verdun's life or death resolve always will move a Prussian Achilles far more deeply than the humanitarian goals of the American, French and Russian Revolutions. It brought out the best in the combat-ants, not their best as human beings, but as Prussians and Frenchmen. In this crucial sense, Verdun was a Prussian, not a French, battle. No less than the Prussians, the French at Verdun subordinated humanitarian, global considerations to the demands of Duty! Honor! Country! What could be more prussian than the martial spirit of a Nivelle or a Mangin! It was the Revolution's universal compassion which insured the victory of Petain's humanitarianism, his grief at the price of Verdun's glory, over Mangin's "Prussian" resolve to win or die whatever the cost. Appeasement - whether of nazis or communists -- would have been unthinkable in a Mangin or a Clemenceau.

Some of the writings of the members of the school that Neumann was something like an honorary member seemed at times to imply that there was something contemptible, unmanly about the Liberal aversion to directly confront the Soviet Union doing the Cold War, almost to argue that if it was necessary to go out in a nuclear flash to retain our honor, let a million fires burn across the globe.3 In that context perhaps it is difficult not to shiver slightly at these words. On the other hand, a characteristic of mine that one might call a negative one seeing that it embraces even very questionable regimes as well as noble ones, is a certain sympathy for any sort of lost world, a vanished horizon for this or that writer. There are limits to this sympathy for Verlorennationheimgesucht, but it is nonetheless a trait of mine, not helped by the suspicion that I may be in the process of becoming such a person myself, albeit hopefully without the exile a man like Neumann endured in the new world. I am reminded slightly of the aestheticist vein that runs through the work of Yukio Mishima, and particularly the tetralogy of novels with which he ended his career, the Sea of Fertility.

On the other hand, there is something to Neumann‘s writing that does seem valuable to me. Our culture is ruled by a kind of thoughtless half nihilism, where one is supposed to carry out that great struggle of wrestling with the angel for only a brief, terrified moment just before the lights go out. West Coasters, Jaffa in particular will often write about the importance of the role of the Socratic gadfly, but it seems to me on the basis of the best of these essays that Neumann was a better inhabitant of that position than the majority of them. It is a valuable if indeed irritating thing to be reminded of the quicksand on which one, and perhaps western civilization at large stands. If I side more with Kierkegaard than Schopenhauer, and prefer Bloom to Jaffa it is still worth being goaded, hopefully to a greater insight.

Neumann, Harry. Liberalism. Durham, N.C: Carolina Academic Press and the Claremont Institute for the Study of Statesmanship and Political Philosophy, 1991.

Everybody’s talking about Thomas Pynchon with the announcement of a new book out this fall, and while I plan on writing this up elsewhere I’ll say that this is basically my criticism of his early work. The paranoia at the discovery of the systems of evil and heritage of doom running back through the enlightenment seem to reinscribe the German idealism that the early novels otherwise aim to refute and imply was always destined to terminate in the V-2 and the death camp, and the Operation Paperclip- imported American military-industrial variants thereof.

As John Barth and other sages tell us, if we honestly believing that nothing is anything, and no action is better or worse than anything else, it really doesn’t matter whether you kill yourself or go on living, or dwell in the polis or in a liberal democracy.

There is a recurring Dolchstoßlegende on the right about the unwillingness of Truman, Kennedy, Johnson (and sometimes Nixon and Reagan) to cross red lines and risk great power confrontation outright in the prosecution of the wars in Korea, Vietnam, Cuba, etc. (The neocons have a similar version of this about Carter’s refusal to send American troops to reinstall the Shah after the Iranian revolution, which my mideast foreign policy historian advisor was baffled by when I brought an example to him.)

I love imagining what that Socrates or Nihilism class must have been like. Jaffa backing Socrates and Neumann back nihilism and just competing to win students to their side

What a screed.

So many rabbit holes. So enjoyed this. Much to digest, confront, and reconcile.

The abyss itself has a different characteristic having read this.