The Historian as Intellectual: Richard Hofstadter & the American Political Tradition

Recently I read Richard Hofstadter’s classic 1948 The American Political Tradition & The Men who Made It, a seminal text of the “consensus history” of the American midcentury. Hofstadter is I think best remembered today as one of the progenitors of what one of my readers called the “bestiary of the right” school of American history, and his reputation has risen in the last decade and a half or so with the corresponding rise in interest in what he described as “pseudo-conservatism” and “the paranoid style of American politics” in several epochal essays of the 1950s and 60s.

the modern right wing, as Daniel Bell has put it, feels dispossessed: America has been largely taken away from them and their kind, though they are determined to try to repossess it and to prevent the final destructive act of subversion. The old American virtues have already been eaten away by cosmopolitans and intellectuals; the old competitive capitalism has been gradually undermined by socialistic and communistic schemers; the old national security and independence have been destroyed by treasonous plots, having as their most powerful agents not merely outsiders and foreigners as of old but major statesmen who are at the very centers of American power. Their predecessors had discovered conspiracies; the modern radical right finds conspiracy to be betrayal from on high.

This is as positive a legacy as any of us are likely to get (this aspect of Hofstadter is for example the one canonized by a Library of America volume) but I suspect that it nonetheless does a disservice to a somewhat protean thinker and historian whose influence can be felt in several other areas of American history. Aspects of both the contemporary progressive tradition which finds the central tragedy of American history the failure of our various great reform efforts (Reconstruction, the civil rights movement) and its mirror in Christopher Lasch and his successors’ skepticism of reform as merely a mask for crusading elite will to power emanate from the pages of Hofstadter's corpus.

The American Political Tradition is less a narrative than a succession of essays on exemplary figures from the American founding up to 1948, men like John C. Calhoun, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt, and Hebert Hoover. The book has certainly aged in certain regards: for one, Hofstadter shares with many historians of his generation a sense that the American Civil war was basically unnecessary & caused as much by Northern abolitionist fanaticism as the existence of slavery as a flaw in the republic, and he thus repeats some dubious lines about natural limitation to the growth of slavery in his essay on Lincoln.1 That said, there is likely some truth to his assertion that Lincoln was a contradictory figure, a man who stood in some regards for two Americas-the backwoods middle west of his youth and the urban industrial machine that he helped to birth during the civil war-that were fundamentally in conflict with each other. In an iconoclastic, perceptive passage Hofstadter even implies that assassination prevented Lincoln from being smeared by association

If there was a flaw in all this, it was one that Lincoln was never forced to meet. Had he lived to seventy, he would have seen the generation brought up on self-help come into its own, build oppressive business corporations, and begin to close off those treasured opportunities for the little man. Further, he would have seen his own party become the jackal of the vested interests, placing the dollar far, far ahead of the man. He himself presided over the social revolution that destroyed the simple equalitarian order of the 1840's, corrupted what remained of its values, and caricatured its ideals. Booth's bullet, indeed, saved him from something worse than embroilment with the radicals over Reconstruction. It confined his life to the happier age that Lincoln understood-which unwittingly he helped to destroy-the age that gave sanction to the honest compromises of his thought.

There is likely something to this argument. Ulysses S. Grant, the Union’s chief general of the victorious latter part of the war and a two-term president in his own right, is remembered ambivalently today for the corruption of his administration, and opinion on the necessity of the Civil War had started to take a turn towards the Lost Cause even before the end of the nineteenth century.

Hofstadter’s overall style here is a middle ground between the “great man” history of his time and the more debunking approach of the generations of historians who preceded and followed him.2 An ex-communist, he was interested in a contrarian reading of the American past without having himself an obvious agenda.3 His heart was with the reformers to be sure-the figure in the book most sympathetically considered is the orator and reformer Wendell Phillips, a man who never held political office-but he was not without his suspicions, and the book and much of his work is that rare kind of cynicism which burns without harming.

Obligatory comic book talk: some notes on The Sandman in light of current unpleasantness

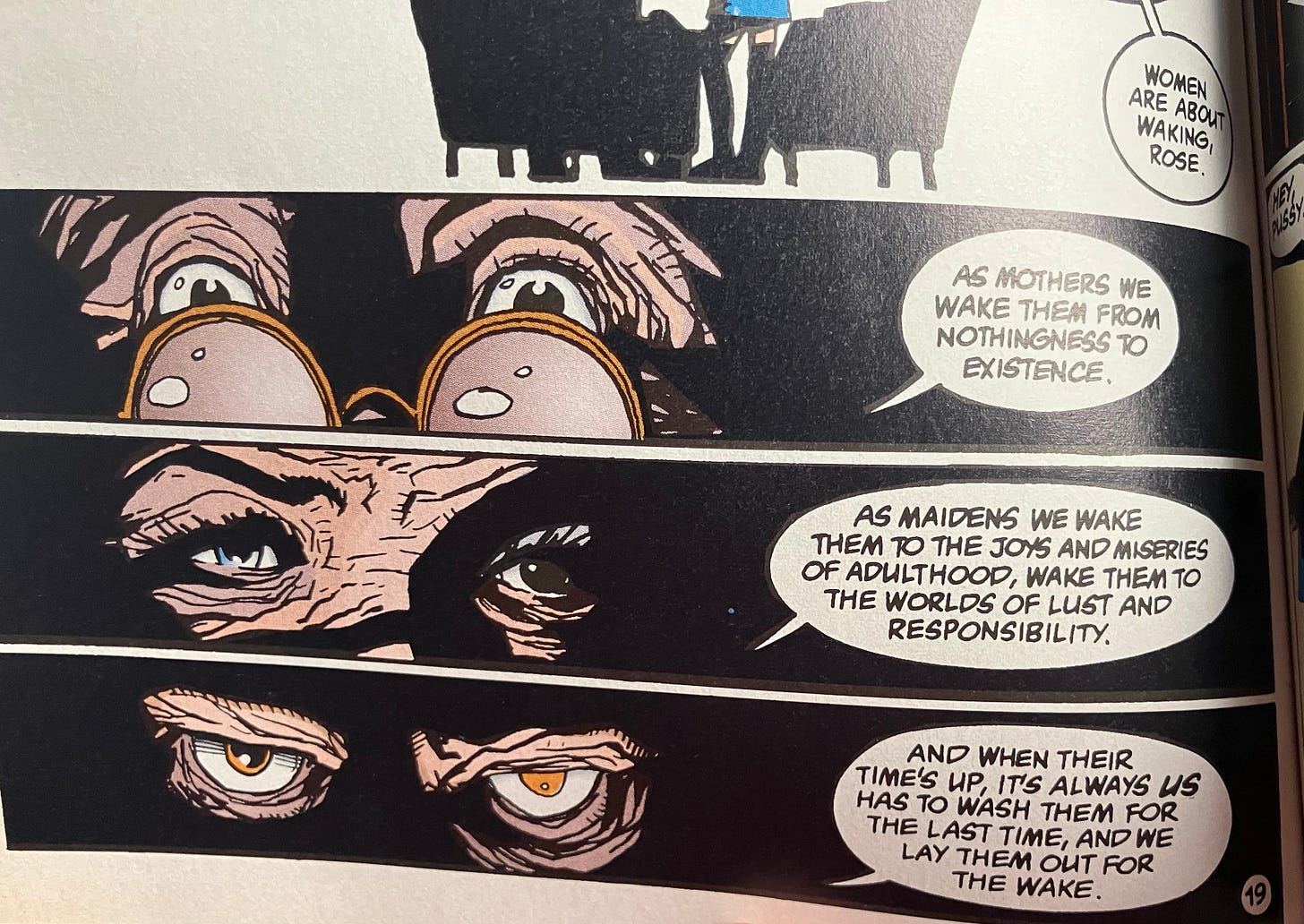

My usual, perhaps too brutal for public consumption take about this sort of thing is that art is separate from its author, and greatness can be the product of monstrousness. The difficulty begins when the text is itself so clearly an aid for the unseemly, as I think there is now perhaps some sense that The Sandman was for Gaiman. Certainly the vampire story structure of some of the episodes-the way that Dream is both the slasher, responsible for so much of the horror and the dreamy boy who saves the final girl at the end is harder to take considering what Gaiman is accused of. I don’t mean to be overly moralistic with you, I like my horror as much as the next person, but this kind of story runs on the slaughter of women, its currency is female flesh. Really, I don’t mean to sound like Andrea Dworkin, but this is a convention of the genre, it’s how this sort of text works. People have been upset about Wanda in A Game of You for thirty years, but he treats her as well as any of the other dead women in the comic really.4

Texts are seducers. Whether this is true generally or simply the result of spending six months marinating in the work of a thinker whose books and pedagogy hinged around making the reader/student feel like a Very Special Boy who gets to think through Machiavelli and Plato with Herr Doctor Professor, I’m not sure, but it seems clear to me at this moment. The Sandman is I think supposed to be a seducer for college aged women with literary interests, run through as it is with references to Shakespeare and G. K. Chesterton, Kipling and postmodernism, a perfect companion for the alternative girl with a collection of The Cure records who wants to look like Death. This is not a unique problem, but it does alter the text. I think The Sandman can and will survive this apart from whatever becomes of Gaiman-it’s a remarkable comic, undoubtedly his masterpiece, and emblematic of its era in ways that become more clear with every passing year-but all the same, one’s impressions can’t help but be changed.

Late Style: Toni Morrison’s God Help the Child

“Stark” is the word to use here I think, maybe “haunted” as well. I first read (I believe) this book not terribly long after discovering Morrison, before the rest of her late work, with the incandescent glow of that main sequence from The Bluest Eye to Paradise still blazing in my peripheral vision.5 I was a bit underwhelmed by it then, finding its contemporary setting not entirely convincing and the characters a little unwritten and at times almost unbelievable. As it happened, God Help the Child turned out to be Morrison’s last novel, and thus bears closer examination. In doing so we find that she has left us in with an appropriate note after all. God Help the Child’s subject matter has a peculiar symmetry with Morrison’s beginning. The climax of her first novel was an elderly pedophile’s letter to God, chastising Him for the world He made,

You have to understand that, Lord. You said, "Suffer little children to come unto me, and harm them not." Did you forget? Did you forget about the children? Yes. You forgot. You let them go wanting, sit on road shoulders, crying next to their dead mothers. I've seen them charred, lame, halt. You forgot, Lord. You forgot how and when to be God.

That's why I changed the little black girl's eyes for her, and I didn't touch her; not a finger did I lay on her. But I gave her those blue eyes she wanted. Not for pleasure, and not for money. I did what You did not, could not, would not do: I looked at that ugly little black girl, and I loved her. I played You. And it was a very good show!

While it is by no means clear that the world of her final novel was in fact constructed by the same deity, something of that spirit remains. Morrison leaves us as she began, but in the intervening years the questions have become less ironic but no less tormented. Soaphead Church has been replaced by two bright young things, products of the America Morrison died in rather than that of her upbringing.6 Booker and Bride have each experienced childhood victimization in their own way, and each ultimately imagines that they can together construct for their child a world without sin. We know better, above all else Morrison knows better. There’s something of late Melville here, the Melville of The Confidence-Man and Billy Budd, of his great short poem “Fragments of a Lost Gnostic Poem of the Twelfth Century.”

Found a family, build a state,

The pledged event is still the same:

Matter in end will never abate

His ancient brutal claim.

Indolence is heaven’s ally here,

And energy the child of hell:

The Good Man pouring from his pitcher clear

But brims the poisoned well.

Morrison doesn't go quite that far, but still something akin to that sentiment exists within her text and its preoccupation with the harms we do to children, the harms we do to each other, harms that she all but states outright we are ultimately powerless to prevent. Morrison at the end of her oeuvre does not reach the nihilistic horror of a Melville or a Twain, of a renunciation of earthly life-and this may well be a mark of her superiority-but she is wide eyed and realistic about our hopes of solving the perennial questions, of righting the wrong(s) at the center of things.7

A child. New life. Immune to evil or illness, protected from kidnap, beatings, rape, racism, insult, hurt, self-loathing, abandonment. Error-free. All goodness. Minus wrath.

So they believe.

Harry Jaffa (more on him coming soon) offers a mixed and in some ways perceptive assessment and demolition of Hofstadter’s evaluation of Lincoln toward the end of his epochal 1959 study of the Lincoln-Douglas debates Crisis of the House Divided.

Hofstadter, it should be remarked, does not share the political orientation of revisionism, which makes Douglas the hero of the effort to avoid the "needless war." Yet his historiography, apart from some highly personal interpretations, seems to be based largely upon revisionism. We shall present some marked instances of this. On the whole, Hofstadter's political sympathies appear to lean toward abolitionism. Randall, Milton, Craven, and others of their school blame Lincoln, with varying degrees of acerbity, for insisting at all upon the universal meaning of the Declaration and making the moral condemnation of slavery a political question. Hofstadter, however, approves of this but believes that the same argument which condemned slavery should have compelled Lincoln to condemn the political inequality which he tolerated. His conclusion with respect to Lincoln, however, is identical with that of revisionism: the pre-presidential Lincoln was above all a demagogue who thought much of what was necessary to get himself elected and little of the consequences to the country of his being elected.

Debunking traditional historical narratives certainly has a place in scholarship, and I’m not opposed to it in any sense. I would however say simply that the main insight of someone like Christopher Lasch (and in her way someone like Ann Douglass) is to pose the question of what purpose the writer has in debunking, and what exactly they seek to exchange for the discredited narrative. One can go too far with this idea as well, take it as a greater revelation than it actually is, but it’s certainly something to keep in mind.

There is, as Eric Foner pointed out in his 2002 book Who Owns History? a certain demophobia to Hofstadter: he grew (especially in the wake of McCarthyism) to mistrust the masses and their passions, and this colors the tone of some of his mature works.

The Age of Reform and Anti-Intellectualism won Hofstadter his two Pulitzer Prizes, but ironically today both seem more dated than his earlier books. Their deep distrust of mass politics, their apparent dismissal of the substantive basis of reform move-ments, strike the reader, even in today's conservative climate, as exaggerated and

There is a very dark reading of the significance of the homeless old black lady who doesn’t like dogs being killed in the storm with Wanda, one that I believe (I don’t have a copy in front of me) Samuel R. Delany approaches in his introduction to that particular volume. In this view, with that catastrophic resolution Gaiman annihilates everything in the story that does not represent himself or that he does not wish to penetrate. It’s a grimmer interpretation than I would make the majority of the time, but once again, one’s perception is inevitably changed.

This is a little bit of creative exaggeration-I wasn’t that systemic about it and there were a few novels in that sequence I hadn’t read at the time, but I got the gist. I understood that this was a Major Corpus, and the ends (and beginnings) of such things are often uneven.

As many contemporary reviews pointed out, it is unusual in this respect within Morrison’s oeuvre, which on the whole leans toward the author’s childhood and early adulthood. This preference is hardly unique among authors, but it is tempting to make something of it with regard to a less-discussed aspect of Morrison’s politics. The black community of Morrison’s pre-civil rights upbringing, several of her books (Sula, Song of Solomon & Jazz in some ways) seem to argue, was separate and unequal, but whole in a way that the legally-integrated world of her middle and old age was in this view not. This tendency exists it should be said, in a productive tension with Christian-American universalism and a deep contempt for the black bourgeois, and is viciously self-criticized in perhaps her best work, Paradise, a novel that pits a vaguely gnostic multicultural and syncretic universalism against the black separatism and patriarchy of the titular community.

At the risk of being crudely biographical, it seems notable that all three of the aforementioned authors buried adult children in their old age.

This is very interesting on Hofstadter. I've always thought that the "consensus school" was basically correct, in that while we Americans disagree quite a bit, the ideological difference between American political parties has never been that great. The west coast Straussians (and many many other people, e.g. Martin Sklar, or Herbert Croly at the time) are right to see a decisive break in our history with the establishment of a modern state in the Progressive Era, a change prophesied by Hegel and Alexander Hamilton and many others. But there has never been coherent conservative opposition to what Sklar called "the corporate reconstruction of American capitalism," certainly not from Taft, Hoover or Eisenhower (who perhaps favored a more oligarchic version of "big government" but never the pipe-dream of its abolition) and not from the Cold Warriors of the Regan/Buckley tradition either. (You can construe Coolidge as an opponent of the "administrative state" and that's why he's a cult figure for some.) In this respect the dismissal of "pseudo-conservatism" as a matter of what Trilling called "irritable mental gestures" is imo correct, although one finds plenty of these gestures in Truman, JFK, LBJ, Carter.... We do have an ongoing fight about the size of government and the relative power of corporations in the direction of it (one in which labor was for a while a contender for influence before it was crushed in the 70s), but it has never been a clear-cut ideological contest.

On the other hand there has been a poisonous and truly ideological struggle over race for our entire history, one about which Hofstadter like most midcentury liberals seems to have been pretty myopic, to be polite. From today's perspective, the central fact of late nineteenth century US history seems clearly to have been not the fight of populism or progressivism against a half-imaginary "conservatism" (as if a Burkean white supremacist like Woodrow Wilson weren't conservative), but the failure of the reconstruction. Had Lincoln lived, we would judge his post-war record primarily, almost exclusively, on the basis of his handling of the reconstruction. The idea that the paradoxes of laissez-faire would have been more important reflects, IMO, a determined effort to avoid thinking about the grubby compromises with white supremacy that made first Wilsonian and then New Deal politics possible.

"His heart was with the reformers to be sure-the figure in the book most sympathetically considered is the orator and reformer Wendell Berry"

I'm confused. Wendell Berry was born in 1934, and in 1948 he would have been 14 years old, so presumably he couldn't have been in *The American Political Tradition*. Berry started publishing only in the early 1960s, and these were novels. What am I missing here?