Hello, and welcome once again. These weekly digests are always messy quilts of whatever I’ve been thinking about, and this one is perhaps unusually so. This week I have some thoughts on the C.G. Jung, and the remnants of the Cathars and Christian dualism and heterodoxy more broadly, with footnotes about Ann Douglas and Hawthorne and the alienness of the Gospels. First, some housekeeping: It occurs to me that my recent approach of “all mythopoetics and theology, all the time” in these digests is maybe not what some of you subscribed for, and I have several standalone essays that should be published in the next few weeks on topics possibly near and dear to my readers, such as neoconservatism, and Nathaniel Hawthorne. I will also be reactivating paid subscriptions and posts in the new year in anticipation of being more productive. Don’t worry though, the free digests will continue. Cheers!

Analytics and criticism: preliminary mutterings about Jung

Last week I was encouraged to elaborate on some apprehensions about the current prominence of C G Jung in certain quarters of the discourse. I don’t really feel able to do that at the current time, although this excerpt from Triumph of the Therapeutic I shared a few months ago captures some of it.

Jung represents a conservative, or traditionalist, trumping of the psychoanalytic game. He is perhaps the most subtle of modern conservatives, trying to save not this tradition or that, but the very notion of tradition, which can be defined, in Jungian terms, as shared archetypes internalized. When the theologians will finally catch up with Jung, they might discover in him that particular psychology for which they have been seeking, in a prolonged agony, a substitute for all those ontologies crumbling at the foundation of theology.

In essence I do worry about the the archetypes, and Jung’s sense that there is something essential behind them, being used to re-hypostatize a Euro-American industrial model of the human, which would seem to me to nullify that which is good and interesting in Jung, ironically putting us right back with Freud and his ordinary unhappiness. There is also the matter that like some other recent subjects of my attention Jung has an inner personal myth, a communion with the spirits underlying his theories of the mind. As with Blake I’m not at all sure that I understand the myth, and I would like to do so at some greater length before I go out on a limb and extrapolate further.

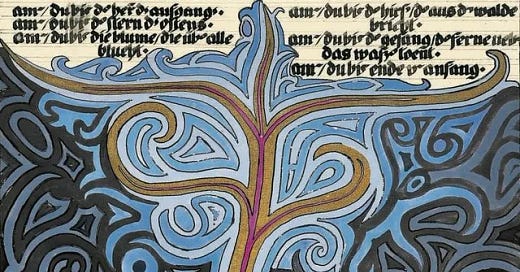

The cruel master of this earth/Holds me bound by death and birth: Catharism,

Partially because I’ve been reading about Manichaeism, partly because I’m rereading the Gospels, and partly because I’ve been reading Ezra Pound, I was thinking about Catharism the other week.1 The story that has come donwn to us via heresiology describes an extremely dualist sect of Christianity bearing certain theological similarities to both Manichaeism and the now extinct Zurvanist sect of Zoroastrianism. The Cathars appear to have believed that God had two sons, Christ and Satan, and that Satan’s rebellion had created this world. Humans in Cathar cosmology are the angels who rebelled with Satan, now embodied and trapped in a cycle of reincarnation within the material world.

Then, l, John, questioned the lord, "How can one say that Adam and Eve were created by god and placed in paradise to obey the father's orders, but they were then delivered to death?"

The lord answered me, "Listen, John, beloved of my father, it is the ignorant who say, in their error, that my father made these bodies of mud. In reality he created all the virtues of heaven through the holy spirit. But it is through their sin that they found themselves with mortal bodies of mud and were consequently turned over to death."

And again I, John, questioned the lord, "How can a man become born in spirit in a body of flesh?"

And the lord answered, "Descended from angels fallen from the sky, men enter the body of a woman and receive the desire of the flesh. Spirit is born then from the spirit and flesh from the flesh 13 So Satan accomplishes his reign in this world and in all nations.2"

The believer in this story would be doomed to reincarnation if they did not become an elect, a process that similarly to Manichaeism involved sanctification and a very extreme renunciation of sex, meat, alcohol etc.

Gnosticism, which perhaps should not be thought of as one thing, but which Catharism is often seen as the final significant manifestation of in the west, often seems to emerge from a desire to elevate the New Testament over the old.3 Hans Jonas in his epochal (if somewhat outdated) The Gnostic Religion makes the claim that this is a form of antisemitism, something I was reminded of the other day by

and bringing up that Simone Weil was influenced by the Cathars.On the other hand, there is from what I understand some fairly heated debate about what the Cathars actually were if they were. Scholarship over the last century has become less and less likely to take the account of the persecuting orthodoxy at its word, and there is reason to doubt how accurately the medieval heresiologists described them as a religious phenomenon, medieval heresiologists having a habit upon encountering heterodox tendencies to go “ah, Manichees/Arians/Gnostics etc.” As I’ve said before, I suspect there is a way in which gnosticism so-called is simply the shadow of everything orthodox Christianity had to suppress to become the religion of Caesar, a haunting but immaterial apparition dogging the psyche of the church down through the centuries. While a strongly dualist heterodox tradition in Bogomilism does seem to have existed in the Balkans during the period in question, it is not always entirely clear that the same is true for the south of France, and the Albigensian crusade, marked for its brutality even by medieval standards, is often seen as partly a power grab by the kings of France against the independent Languedoc. This ironically may perhaps be closer to the spirit in which noted antisemite Ezra Pound cites them in his Cantos, that of the Troubadours and the courtly romance tradition, something closer to the Goddess-cult Robert Graves was describing last week.

Born with Buddha’s eyes south of Mason and Dixon: Thomas Pynchon’s American odyssey

I commented around this time last year that I was reading Thomas Pynchon’s 1997 faux 18th century mock-epic novel Mason & Dixon, before failing to keep you posted at all on that over the last 12 months. A vast, rollicking pastiche of the 18th century Novel a la Sterne or Fielding, Pynchon chronicles in buddy-comedy form the efforts of the titular pair to survey the eponymous line dividing the colonies, and eventually America. As an obvious twin to one of my favorite books, John Barth’s Sot-weed Factor, which has a very similar (if less extreme, only Barth’s dialogue and genre is in 18th century English, while Pynchon’s entire novel is written in it) conceit, I’d been meaning to read this one for a while.

It’s an interesting book in the development of its author: early Pynchon is systems-crazy, besotted with conspiracies and the revelation of the almost Satanic evil under the skin of the world in a way that tends in my view to replicate rather than replace the European idealism those books otherwise seek to indict. From Vineland on there is a shift in his writing, which if never exactly full of well rounded characters in the way some of his contemporaries could manage, nonetheless become increasingly people-centric, about what it would be like to live in the world of a Thomas Pynchon novel. Mason & Dixon continues this evolution, being as much about the friendship between the depressive Mason and more typical Pynchon protagonist Dixon as all the myriad strangenesses they encounter along the way, from Benjamin Franklin, omniscient mechanical ducks, George Washington and Learned English Dogs to the obligatory jesuit conspiracies. Among other things it’s a fascinating meditation on America itself.4

"Howbeit,- the Secret was safe until the choice be made to reveal it.

It has been denied to all who came to America, for Wealth, for Refuge, for Adventure. This New World' was ever a secret Body of Knowledge,-meant to be studied with the same dedication as the Hebrew Kabbala would demand. Forms of the Land, the flow of water, the occurrence of what as'd to be call'd Miracles, all are Text, — to be attended to, manipulated, read, remember'd."

"Hence as you may imagine, we take a lively interest in this Line of yours," booms the Forge-keeper, "inasmuch as it may be read, East to West, much as a Line of Text upon a Page of the sacred Torah,- a lel-Jurian Scripture, as some might say,— "

"— Twill terminate somewhere to the West, no one, not even you and your Partner, knows where. An utterance. A Message of uncertain length, apt to be interrupted at any Moment, or Chain. A smaller Pantograph copy down here, of Occurrences in the Higher World."

I was promised that the second half was much stronger than the first, and I am happy to report that this is the case. As the line nears completion the book becomes increasingly haunted by the future, by the weight of westward expansion, industrialization and the eventual civil war that will take place in a little over a century hence. As Mason and Dixon part and then age, Pynchon paints a suitably autumnal picture I wouldn’t have imagined him capable of based on previous work. But for the language it might be my favorite Pynchon-who knows, on inevitable reread it just might be!

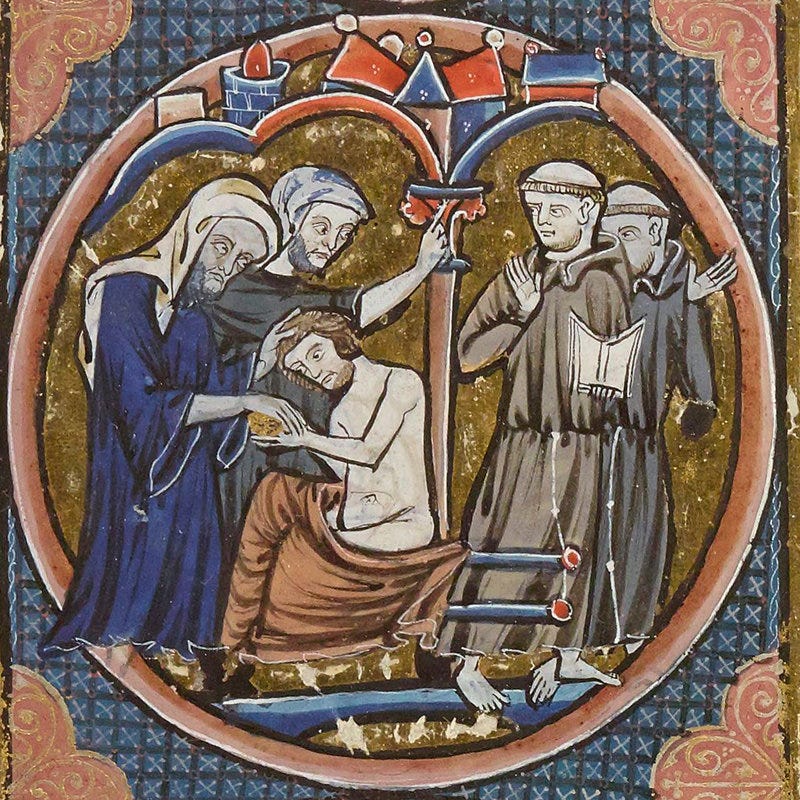

This week I reread the Gospel of Matthew, the book of Proverbs, and part of the Gospel of Mark in the Revised Standard Version. If like me you were raised in a fairly easygoing version of the Christian religion, returning to the close reading of the gospels can be a deeply strange and indeed sometimes frightening experience. The Christ who shines on the page really does seem alien, as threatening in some ways as He must have seemed to the late second temple Jews and Romans who encountered the man and His teaching. I’ve long suspected that this is disjunct between the Christ of the gospels and the hegemonic, imperial religious societies that have followed Him are a major part of why there are so many heterodox Christianities.

Quoted from the Bogomil text “The Gospel of the Sacred Supper” translated by Willis Barnstone, in The Gnostic Bible: Gnostic Texts of Mystical Wisdom from the Ancient and Medieval Worlds.

On my fascination with this topic, I will say this: Harold Bloom once wrote a book (I have not read completely) in which he makes the claim that the United States is gnosticism’s nation. I believe he had in mind something like Mormonism and the new age movements of his own time, but I’m also reminded of the extremely dualist form of many of the more vernacular varieties of American protestantism, where one encounters the idea that this world is the devil’s kingdom, that indeed Satan is contending directly against the Lord, with his victory a real possibility, rather than the defeat that is the forgone conclusion of most versions of the Christian story.

I’ve been revisiting Ann Douglas’s The Feminization of American Culture for that upcoming essay on Nathaniel Hawthorne. One of the central themes of Douglas’s text is a lamentation of the evolution of New England Calvinism-which Douglas views as a masculine, uncompromising force opposed to modernity-into the liberal, sentimental congregational tradition which she views as ancestral alongside the cultural production of Victorian middle class women to the mediocrity and of 20th century mass culture.* Hawthorne is more ambivalent than that about puritanism, but there’s something of that attitude to his work nonetheless. Everyone knows the works that criticize puritanism, like The Scarlet Letter, The House of Seven Gables, but in stories such as "The Celestial Railway” or “The Maypole of Merry Mount” in other ways, there is a rather different attitude, one that does rhyme in certain ways with Douglas’s account.

*The (seemingly left-identified, although I’m not totally sure what Douglas’s politics are) late 20th century radical academic mind’s affection for conservative or reactionary positions in modernity is a topic that fascinates me.

I read a bit over half of Mason & Dixon on a long flight across the Pacific and enjoyed it, but for some unknown reason I never picked it up again. I might have to this year.

Interesting! Re Bloom, he defines American Gnosticism as possessing three traits, to greater or lesser degrees:

1. The human soul is created before

Creation, and thus does not fully belong in Creation

2. Knowledge is more crucial to salvation, broadly defined, than belief

3. The loneliness of the vast American land shapes all of these beliefs.

Which shapes Mormonism for sure, but also Adventism and even some forms of evangelicalism