On this Fine Conservative Night

Some musings on contemporary neoconservatism and related themes

I originally intended to follow up the trilogy of essays on neoconservatism I wrote last fall with a coda to be entitled “The Ouroboros of Contemporary neoconservatism.” The title was meant to evoke the phenomenon by which thinkers and writers who defined themselves against the neoconservatives of the George W. Bush era swung to the right during the Obama and Trump presidencies in ways that mirrored the original neocons of the 1970s. For a variety of reasons I put that project on hold for over a year, but it seems clear to me now that we are living in a period that is at least neoconservative, if not even to the right of that, and thus I thought I would share some of my thoughts on both that topic and some others that have been kicking around in conversation over the last little while. This isn’t really an essay with a thesis so much as a more focused version of one of my weekly digests, let me know what you think of the format.

The ouroboros of neoconservatism in the new twenties: romanticism and “inner decolonialism” on the new right

One of the central divergences between what I will for the sake of clarity call “classical neoconservatism” and its successor in the present moment concerns its relationship to romanticism as a whole. At the risk of generalizing, classical neoconservatism was broadly anti-Romantic while contemporary neoconservatism is characterized by romanticism.1 The original neoconservatives, like the cold war liberalism they emerged out of, were concerned with stabilizing complex systems and while they did entertain critiques of them (neoliberalism and decentralization are arguably downstream of this) were largely devoted to institutions and preventing their collapse. Contemporary neoconservatism on the other hand is much more of an ideology (to the extent that it is an idea) of radically autonomy and skepticism of institutions, particularly those of the state. Paradoxically it also shares a certain patriotic and even nationalistic sentiment with what I described as the prophetic second generation of “classical neoconservatism.” This too is tied to the shift in temperament, to quote a recent article by

on the topic of contemporary romanticism as discussed by and on a February 2024 episode of ’s podcast.The most characteristic political expression of European romanticism was nationalism, the defense of particular (not universal) identity, of local specificity, of irreducible complexity against the (supposed) Enlightenment project of flattening, homogenizing, universalizing. This is not essential to the discussion, but it is worth noting, as it potentially gives the concept of romanticism more purchase on our own moment. Nationalism is famously slippery, a force both of bottom-up emancipation and top-down authoritarianism. It could be helpful to analogize the present to an earlier period in which rapid, universalizing technological change produces a bitterly fracturing, potentially violent and deadly, obsession with particularity.

Writing about the evolution of ideas is a close cousin of biography, and over time I’ve noticed a pattern in some of the thinkers I’ve observed. The archetypal contemporary neocon probably grew up either outside the center or maybe in an immigrant community in a right leaning or apolitical background. After 9/11 many of them swung hard left in response to Bush II, got screwed by the recession, and slowly lost faith over the course of the Obama presidency. They may or may not have been “woke” but came home to the right at some point during the Trump and Biden years due to a variety of factors ranging from gripes about dominant left liberal culture to fears about Covid restrictions or in some cases financial incentives-one can be quite successful as an edgy truth teller.

In my investigations of the original neoconservatives I’ve tended to downplay the Trotskyist connection-this is maybe temperamental on my part, I also tend to downplay the Strauss connection-but I do think millennial socialism and opposition to Bush II’s imperial misadventures is relevant to the discussion of present-day neocons. Paradoxical though it has often seemed to me, one of the central ideological features of contemporary left-right journeys is something that might be seen as an “inner decolonialism.” In this hermeneutic, social liberals and progressives are viewed as something like an alien elite colonizing socially reactionary cultural blocs, marginalizing the rest of the country from their coastal or metropolitan enclaves. For some contemporary thinkers right or reactionary efforts to limit immigration, reintroduce traditional sexual and gender mores etc; are thus a form of "decolonial” struggle, a nationalist resistance to inner empire. To some extent this is not a phenomenon of left or right but what

borrowing terminology from Martin Gurri recently described as the “center” and “border.”With the Border newly empowered with investigative tools as well as the ability to rapidly communicate with itself, the usual tricks of the Center — the lazy appeal to ‘Authority’ — start to collapse. The history of our era, not surprisingly, is the Border picking the Center to shreds. The comedy is the satire of the Border — Jon Stewart, Stephen Colbert, The Onion News Network — getting just endless mileage out of the self-seriousness of the broadcast news networks, which were able to get by with their pompousness for so long (“and that’s the way it is,” that kind of thing) because there was no one in position to mock them. In social relations, the Border effected a kind of bloodless revolution against the Center, with Twitter mobs throughout the 2010s accusing those in positions of power to be inveterate sexual predators or closet racists or a combination of the two. From the other side of the political spectrum, Donald Trump engaged in a complicated sort of performance art — playing simultaneously as a figure of the Center (the gold-plated mansion, and then as the honest-to-goodness president) and as the voice of the aggrieved Border.

As nationalism has been the undoing of empires in modernity there is a great deal of emphasis on the familial authorities, on the little fathers and mothers whose role the state and industry absconded with over the course of modernity. To quote a favorite thinker of the contemporary neoconservative, Christopher Lasch, in his most famous book:

Having surrendered most of his technical skills to the corporation, he can no longer provide for his material needs. As the family loses not only its productive functions but many of its reproductive functions as well, men and women no longer manage even to raise their children without the help of certified experts. The atrophy of older traditions of self-help has eroded everyday competence, in one area after another, and has made the individual dependent on the state, the corporation, and other bureaucracies.

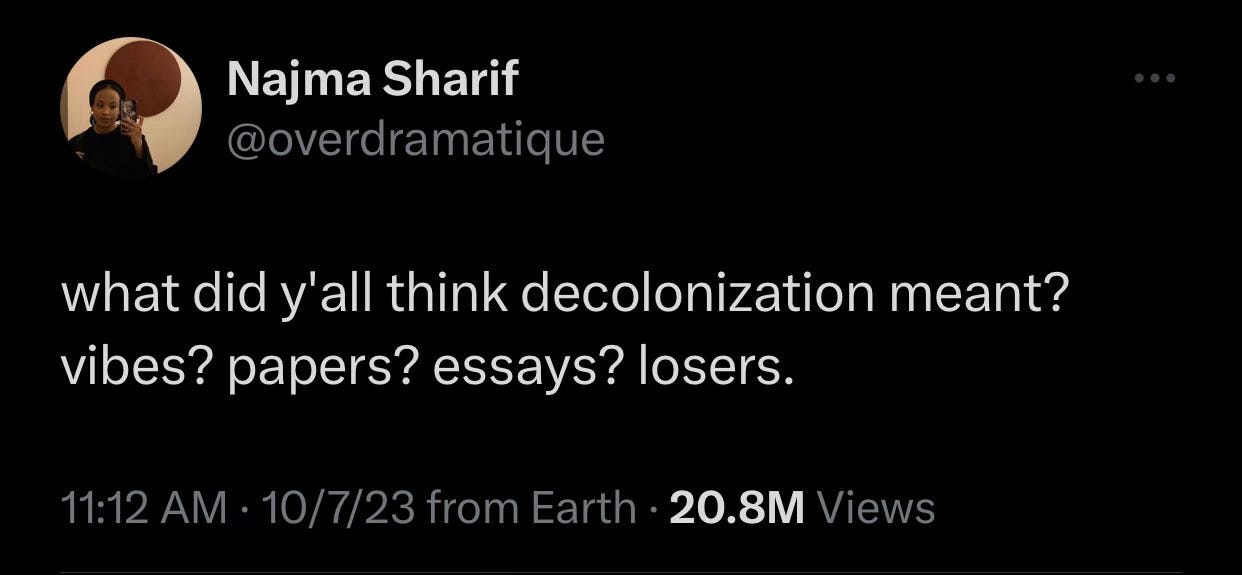

For the contemporary neocon natural order must be restored. Parents must again own their children, communities their laws, the Nation its citizens, its citizens their bodies as far as they obey Nature and its imperatives. The outer decolonialists on twitter so famously queried last year in response to outcry by soft hearted skeptics of revolutionary violence:

One wonders: what misapprehensions will be dispelled by “inner decolonialism?”

Miscellaneous thesis on journeys to the right

I.

A recurring trend in the output of members of this group of thinkers is the presence of something like an upside down critical theory, in which the left and the institutions of the left are shown to be enmeshed in the state and empire in ways evaded by academic socialism etc. In lieu of revolution traditional lifestyles, petit-bourgeois economics, and alliance with the captains of industry and the ideologues of the right are proposed as the solution to this dilemma. I have suggested before that this “upside down theory” cuts both ways, however, and is still in some respects contradictory if one still holds to the values of a liberal democratic civilization. If one does not, this critique can be discarded.

II.

Contemporary neoconservatism is perhaps not even neoconservative in the more specific sense of the word, retaining from its predecessor only the definition of a post leftist right movement within the confines of a liberal system of values. Some seem to move through neoconservatism on the path to something harder edged, IE; Wesley Yang or Nina Power, others remain there. The varied progeny of the Lasch-Paglia intellectual dyad amongst the online take-haver set are perhaps the best example of this. A now ex-friend (to borrow a title from Podhoretz père) once perhaps uncharitably described this sort of thing as “fash-curious liberalism”-opposed to Covid restrictions, disillusioned by hookup culture and secularism, entertaining the idea of biological racism, but also not yet ready for Caesar. There is a particular fusion of Neo and Paleo on the intellectual right today that someone like

is better qualified to discuss than I.III.

The original neoconservatives often accused the 1960s counterculture of fascism or nazism, an accusation that I found confusing when I first began seriously researching this topic in college. Weren't the hippies mostly left-leaning? Philistine that I was at the time, I had mostly not read the great novels and poems of the interwar period, which would have set me straight. The radicalism of the sixties rhymed in certain important ways with that of the twenties and thirties, washed out with acid and free love sure but a certain core skepticism of liberal modernity, enthusiasm for mysticism and the “primitive” and simultaneous revulsion and fascination with technology passed along and now returning in something like an atavistic recurrence. Ezra Pound is here, man, he’s living large right now, ordering General Tsaos in a Chinese restaurant in Wellesley. I don’t quite believe this, but the 2020s rhyme just enough with the 1920s to make me nervous.

IV.

I am very uncertain of the role religion and spirituality play in all of this. Much has been made of the catholicism of the metropolitan right, but one wonders if this will turn out to be as much of a red herring for the future development of the right as the white ethnic multiculturalism of the original neoconservatives. The culture of the United States belongs on some ineffably metaphysical level to Calvinist Protestantism after all, even if hardly anyone is a Calvinist anymore. I wrote about the currently right-coded spiritual dimensions of our time at greater length here.

V.

It is not yet clear and will not be until next year if not later how much of this all was merely oppositional, and how much has been about genuine principles and belief. There has been a great deal of anger in the last four years at liberals about Covid lockdowns, about inflation, about grievances around the social justice movements of the last decade, and thus the right has become a vehicle for a number of dreams that it will very likely fail to execute now that it once again grips the levers of power. To be blunt, the odds of the incoming administration either launching a war or continuing to rubber stamp further atrocity on the part of American allies is high. It’s maybe a little paternalistic and a bit caricatured of me-what aren’t I worried about?- but I do worry about some of these people. It’s not that I think there aren’t reasons to oppose contemporary left liberalism or feel some sense of schadenfreude about the election so much as that I worry that a bunch of people who do not know the American right in the way that those of us who have studied or have been rightists ourselves do latched on in the last five years and are about to get burned quite badly.

This may well be projection-I had an experience years ago in which a cause I signed onto from the perspective of supporting freedom of speech and what I took to be principled liberalism turned out to be merely reactionary, a con played on us by ideologues who used those principles as a Trojan horse to bypass critical thinking to further their agenda, and am thus always a little concerned about such things.2 I don’t necessarily think we should shut down dialogue-I’ve written against that here-but I do think vigilance is called for. It is so easy to be passionate in the darkness, only to find oneself bursting out into the cold light of day waving the banner of a cause that was not at all what one enlisted for in the gloom.

In defense of the English department terminology, I think it matters enormously that thinkers like Lionel Trilling and Norman Podhoretz were literary intellectuals who favored the 19th century novel, or that Gertrude Himmelfarb was a historian of Victorian England. The crossroads between literature and politics (I might add the intangible third road of theology) are bloody indeed, and we ignore them at our peril.

The esoteric reading could perhaps be that I warn you about neocons to camouflage the similarities between my own very boring politics and elements of theirs. Much to consider.

This is really interesting but I don't know if I quite follow.

I think Pierre Manent once said that the expression "neoconservative" is confusing because it makes people think both a body of ideas and a typical intellectual trajectory. (IIRC he was saying Ratzinger was a neocon in the second sense but not the first.) I think that you are making a similar distinction and are (at least in this piece) are interested in people who have been driven right by leftist effervescence. They are neo- and not paleocons, to the extent that they are, because they wind up in a position like Ratzinger's / The Free Press, not the SSPX / Alex Jones. (I'm happy to say that I'm a New Romantic who rejects futile and exhausting hyperpolitics but I guess if you don't see things this way I'm a neocon by tendency.)

Isn't the differentia specifica of neoconservatism as a body of ideas, however, commitment to an aggressive US foreign policy that will remake the world in accord with Western Values? One that isn't deluded by rhetoric about International Order and wisely knows it has to act now because it doesn't think that History is on its side? I've been really struck by Adam Tooze's running commentary that the real heirs to the neoconservatism of the early Reagan and Bush II eras are Biden and Jake Sullivan (here https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/oct/10/war-middle-east-ukraine-us-feeble-biden-trump, and at greater length here https://adamtooze.substack.com/p/chartbook-331-46-in-medias-res-a.) Maximum pressure on Iran, in support of Israel, vs. Russia in a proxy war, vs. China in a Cold War. This was frightening and dangerous in a way we Americans had difficulty taking seriously because we are so navel-gazing. It is why I've found this whole "have Democrats rejected neoliberalism" debate between Klein/Yglesias and The American Prospect bizarre. The Official Democratic Party rejected "neoliberalism" in the name of Cold War II with China, and I don't think the part of the left that's interested in electoral politics noticed or cares?

Anyway sorry for this disorganized rant, which I realize isn't as much of a comment on your post as I hoped it would be. I would never vote for Trump, I am a milquetoast social democrat left-liberal, but I don't think we Americans are sufficiently scared of the political center. This leaves me unsure exactly what political epithet to give myself.

I think this is really well observed. Yeah, I'm not sure the neo-paleo split obtains anymore, so there's a lot of cross-pollination. But one key thing to think about in all this is Israel: did the paleo right accept a more openly ethnonationalist Israel?