This is the purpose of Camille: on Sexual Personae and its uses

I’ve been rereading some of the individual entries in Camille Paglia’s 1991 tome Sexual Personae. In particular I was intrigued to revisit her thoughts on the various American romantics.1 Paglia is a somewhat difficult thinker to do justice to, perhaps best described as a kind of inverted radical feminist or cultural theorist in the French mode.2 Simultaneously a biological essentialist who often does seems to think that women are actually inferior to men, Paglia also holds a certain affinity to the side of feminism which opposes the conventionally feminine and the domestic.

The realm of number, the crystalline mathematic of Apollonian purity, was invented early on by western man as a refuge from the soggy emotionalism and bristling disorder of woman and nature. Women who excel in mathematics do so in a system devised by men for the mastery of nature.

The central idea of Sexual Personae, and Paglia more generally is what she refers to as the “chthonic.” Nature as woman, the horror of nature, that which men lack, are excluded from, desire, are repulsed by, etc. From this revulsion and lack all art and all civilization emanate according to the overarching narrative provided in the book. She sees this drive to escape from female nature as the source of the aesthetic, androgyny, and pedrasty, and sympathizes with a rather different binary combination of those things than you might expect. The aesthetic mind of the modern west, she implies, is a male crystalline pedophile intelligence six miles in the sky, futilely seeking to escape Nature.

Projection is a male curse: forever to need something or someone to make oneself complete. This is one of the sources of art and the secret of its historical domination by males. The artist is the closest man has come to imitating woman's superb self-containment. But the artist needs his art, his projection. The blocked artist, like Leonardo, suffers tortures of the damned. The most famous painting in the world, the Mona Lisa, records woman's self-satisfied apartness, her ambiguous mocking smile at the vanity and despair of her many sons.

Everything great in western culture has come from the quarrel with nature. The west and not the east has seen the frightful brutality of natural process, the insult to mind in the heavy blind rolling and milling of matter. In loss of self we would find not love or God but primeval squalor. This revelation has historically fallen upon the western male, who is pulled by tidal rhythms back to the oceanic mother. It is to his resentment of this daemonic undertow that we owe the grand constructions of our culture. Apollonianism, cold and absolute, is the west's sublime refusal. The Apollonian is a male line drawn against the dehumanizing magnitude of female nature.

People tend to mostly brush off Paglia’s claim to transmasculinity as a troll, a mere provocation, but it makes a lot of sense to me. She seems to have a real libidinal investment in, and identification with a kind of straight masculinity that fits in uneasily with the women's cultural tradition she tries to be faithful to, with its misandric sense that men are idiots that God (or Nature) has nonetheless set over us. The way this works out in Sexual Personae is that Paglia is spiritually in the camp of the androgynous post Romantic artist, but her biological essentialism prevents her from fully embracing him, and so she is always mocking, belittling, questioning why he isn’t the genuine article.

I like Sexual Personae but tend to find Paglia’s influence somewhat pernicious: one may sometimes be tempted to agree with her critiques of this or that line of feminist argument, but nonetheless the mode of basically misanthropic conventionalism leaves something to be desired as well. Like many other thinkers who imagine themselves to inhabit a decadent culture, feminine and over-civilized, she places far too much value on a male cruelty that may appear liberating if you’re enmeshed in its opposite, but isn’t really a solution either.3

It has always seemed to me that there is an element in her work of trying to have her cake and eat it too. Yes, all sex is perversion and what Freud said about ordinary unhappiness is true, but so is everything Nonna said about men and women and the way they behave. This fits very well into her role in the intellectual ecosystem of the present.

One of the primary forms the backlash to the mores of hegemonic 2010s progressivism has taken thus far has been the embrace of a mode of essentially suburban reaction, an iteration of middle-class neoconservatism big on received wisdom and the idea that people just need to grow thicker skins. This poses a problem in theory, as in its original demotic form this sensibility had little sense of the aesthetic. One of the purposes of Paglia is to provide that sense, to create a justification by which the merely traditional is in fact sublime, depraved, subversive. There is probably something-if only sociologically-true about the Naomi Wolff quote about her being “the nipple-pierced person's Phyllis Schlafly who poses as a sexual renegade but is in fact the most dutiful of patriarchal daughters.” Still, not many can write a book as consistently interesting as Sexual Personae, even if it is perhaps best taken in small doses, with a few grains of salt standing by.

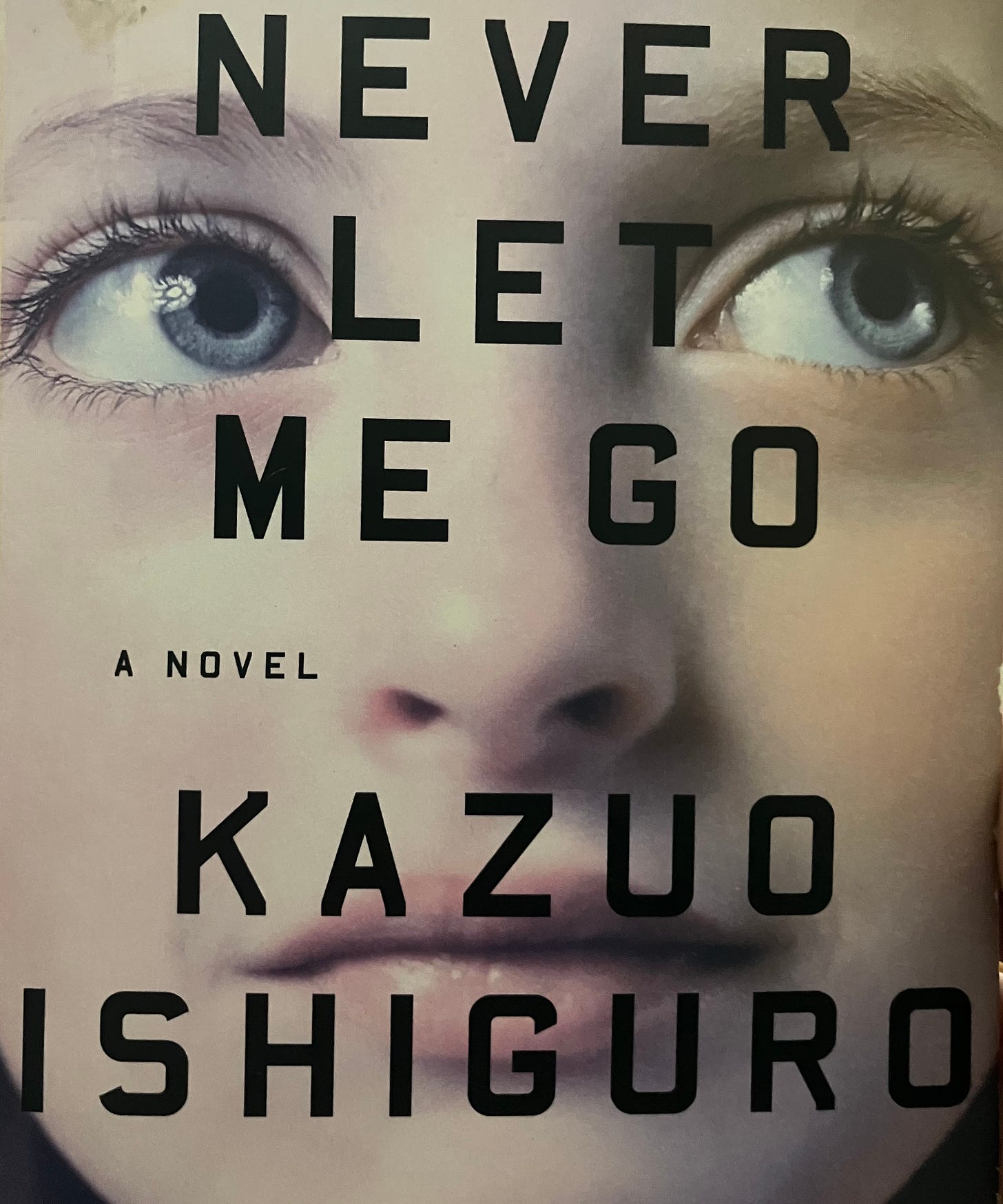

In notes recently I shared an older mini-essay I was recently reminded of. It’s not at all what I set out to write-an extrapolation via his 2006 masterpiece Never Let Me Go of the issues I sometimes have with Kazuo Ishiguro. For whatever reason what I produced was sort of neither flesh nor fish: theological but not theology, psychological but not psychology, emerging as an attempt at literary criticism but certainly not that either. It’s a bit of a botch, and to be completely honest I’m more than a little embarrassed by it, but it is a very pure distillation of….. something I was feeling at the time.4 Gnostic Augustinian liberal aestheticism perhaps?

There is no return to where we were before that is in any way desirable, and so we are left with the task of holding two opposing thoughts at once. To perceive the beauty and decay inherent to all things at the same time without allowing one to annul the other is the urgent task of the moral aesthete, a task that we’ve neglected for far too long.

Nobility & Neoreaction: some musings on Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Down (10/23)

This week I finished reading Kazuo Ishiguro’s 2006 novel Never Let Me Go, often acknowledged as his masterpiece. A “stealth sci-fi” novel written from the perspective of a member of a class of disposable clones bred for organ harvesting in an alternate 1990s Britain, it’s a chilling bildungsroman that entirely lives up to the hype as one of the great books of our young century. The most striking thing about the text to me is that the worldview of Kathy H and her fellow clones is fundamentally postliberal and perhaps even postromantic—they seem unable to imagine that the world they inhabit might be wrong or to want to escape from it.5 Indeed, the best that can be hoped for, the most optimistic dream is for donation and ultimate disposal to be deferred for a few years in the name of love!

I’m not sure I’ve read enough of either’s corpus to make this argument credibly, but there’s something in Ishiguro that reminds me of Thackeray, especially the Thackeray of Vanity Fair—in both one has a sense of the English realist novel unmoored and decentered, “living without God in the world.” Kathy H. might not be as ruthless or amoral as Becky Sharp, but hers is a later age that can more truly inhabit the adage of a “novel without a hero” an age without any prospective avenue of escape or even the consciousness that one could exist in some religious or philosophical sense. I’ve struggled with this side of Ishiguro-the nihilistic quietism- in the past, something I (not entirely successfully) tried to elucidate last week.6 Even if it is true, it seems to me a crushed, defeated way of viewing the world-the Nobel committee described him as Austen meets Kafka, and I think perhaps he captures something of the problems I occasionally have with both of them-the stifling, insular domesticity of Austen and the enervating sense that in modernity one cannot really finally do anything that one gets at times from Kafka.7 It’s funny, because I’m not usually a vitalist this way about fiction, but there is something here I revolt against on a fundamental level, despite that Never Let Me Go is a masterpiece.8

On the 19th century novel as the basis for further development

One of the most interesting pieces of writing to cross my path on substack in the last few weeks was this manifesto about the 19th century novel from

. She argues, it seems to me sensibly, that the literature of this period is the most important material for an aspiring writer of literary fiction.What I'm capable of stating quite strongly is that people who aspire to be writers of fiction ought to read the great 19th-century fiction writers.

Generally speaking, we read the classics for two reasons. The first is that they expand our ability to read, write, and argue. The great 19th-century novels are somewhat long and are usually written (even in translation) in a more difficult syntax, with longer sentences and more dependent clauses, in a way that is typical of how people wrote in English until quite recently. Reading these books will train you to read and concentrate. But to do so without conscious effort. The books don't need to be studied; they can just be enjoyed.

Dickens, Eliot, Emily and Charlotte Bronte, Austen, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, and Gogol—these authors ought to be enjoyable. They might not be initially, but I have a hard time imagining that any aspiring writer of fiction won't find at least one book amongst this clutch that grabs their interest. And after reading that book, they'll be better able to read others.

There is something unique about the 19th century novel that’s hard to quite put your finger on. When I was younger and dumber I used to think this had to do with certain existential certainties I foolishly imagined were more easily held in the nineteenth century. It is true that for most of the period you get less of this in the novel, but turn to poetry or philosophy and it’s a different story, the century of Darwin and Nietzsche, the epoch of the death of God.

At a time to which we of today look back with nostalgia, so innocent of mechanism does it still seem, he is remarking an influence which the machine, or the idea of the machine, exerts on the conduct of life, imposing habits and modes of thought which make it ever less possible to assume that man is man, and he utters this observation in the same breath in which he speaks of the culture's characteristic demand that one "be somebody'.9

Old Matthew Arnold’s poem (begrudgingly included in the anthology I stole this from by Harold Bloom, who remarks that he “wasn't a poet) will do nicely here to illustrate the point here.

And yet, there is something about the 19th century novel. You can’t quite put your finger on it but it is there in all its intangibility, staring out at you. Perhaps because the past is in some way the past, things do seem more, settled? somehow. Of course you zoom out on the picture and the situation becomes much less rosy. Colonialism, slavery, and a myriad of horrors abounded. It’s not even true that there weren’t major European land wars over the course of what the British historian Eric Hobsbawm called the “long nineteenth century” even if there were fewer of them than in the periods before and after!

Also interesting is Naomi’s assertion regarding modernism-

I find that all the quibbling about these lists tends to be about the 20th-century writers. Which is definitely fine, it’s fun to argue—but in practice very few people are reading Milton without reading Woolf. I love Woolf, but you can spend your life reading just Woolf, Joyce, Faulkner, etc! Modernism sometimes seems like a bit of a trap to me—a sterile blossom. Definitely read the great modernist classics, but if you were to start skipping books I’d say Woolf is more skippable than, say, George Eliot.

I’m not completely sure I agree with her here, but I’m also not entirely sure I disagree! There is a tendencyin contemporary bohemia-both aesthetic and political- toward trying to do Modernism, Again that I find pernicious even if it’s not entirely clear that we’re really capable of the complex social tapestry of a Balzac or Elliot anymore. On the other hand many of the most interesting novels of this century evince an ambition to synthesize the two. I have mixed feelings about both of these traditions. Virginia Woolf and György Lukács are raging inside of me!

She is (as one would expect) very attuned to the climate of pervasive gender trouble and resentment of feminine domesticity that runs through the great male American writers of the mid 19th century.

This is not to say that she isn’t easy to quibble with- I do think most criticisms of Paglia wind up snagging something real-only that there is more happening under the hood than one might believe based on those denunciations. It can be argued for instance, that her work doesn’t quite escape from the influence of its two most significant predecessors, her mentor Harold Bloom and idol/rival Susan Sontag, and she probably was a bit too focused on positioning herself in the discourse during her most productive years.

My other suspicion of Paglia is that she’s just doing a kind of Nietzsche impression, and as with many of his works reading her is frequently an exercise in alternately thinking “how insightful!” and rolling one’s eyes.

Why did I disinter it then? Because of my continuing interest in the fringes of psychoanalysis. It’s the most Jung-influenced thing I’ve ever produced.

For more on this sort of thing I direct you to the excellent John Pistelli review of the book, which reads NLMG as embodying something of the spirit of our age, the century of the longhouse and the hospital bed (he doesn’t use those terms, and I wouldn’t either, but something like them is perhaps implied by the logic of the review.)

Kathy H. lives not only after God but also after the religion of humanity that supplanted Him, a progressive faith enjoyed only in the novel by the elite class that exploits her and consigns her to the realm of the soulless. And she does not seem to place any particular value on the claim that she has a soul, nor does she join any resistance movement to claim her human rights; she only wants as good a life as she can get for herself and for those closest to her.

I don’t know why this wasn’t apparent to me a year ago, but there's clearly in part a cultural difference going on here-the naive American unable to metabolize the stiff upper lip and sense that managed misery is all there ever can be of the English writer.

Another missed connection here is perhaps that both Austen and Kafka are very funny, especially if one’s comedic sensibility leans toward the cruel or horrific.

In imaginative works I’m temperamentally for the most part aligned with what I’ve described elsewhere as the prophetic rather than legalistic tradition. There are other places-politics often included- where I’m much more of a legalist, but in fiction I tend to prefer that there always be an avenue of escape, some lonely place to rage at the heavens, etc. I struggle not to put this in crypto-theological terms.

Lionel Trilling, Sincerity and Authenticity

Paglia -> Ishiguro -> Brand New

Interesting read. The summary of Paglia really reminds me of when I was doing work trying to dissect Jordan Peterson and his project of essentially trying to take suburban common-sense around topics of gender and meaning and dress them up with a more academic aesthetic. The sure which of us suffered which of us suffered more for having to read our respective tomes, *Sexual Personae* or *Maps of Meaning*.