Poetical-Philosophical Miscellany

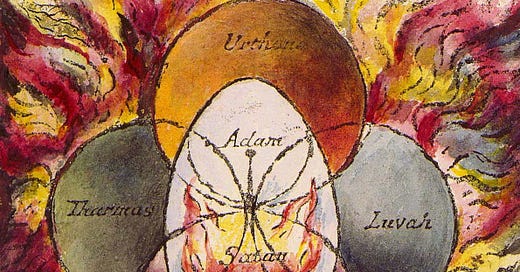

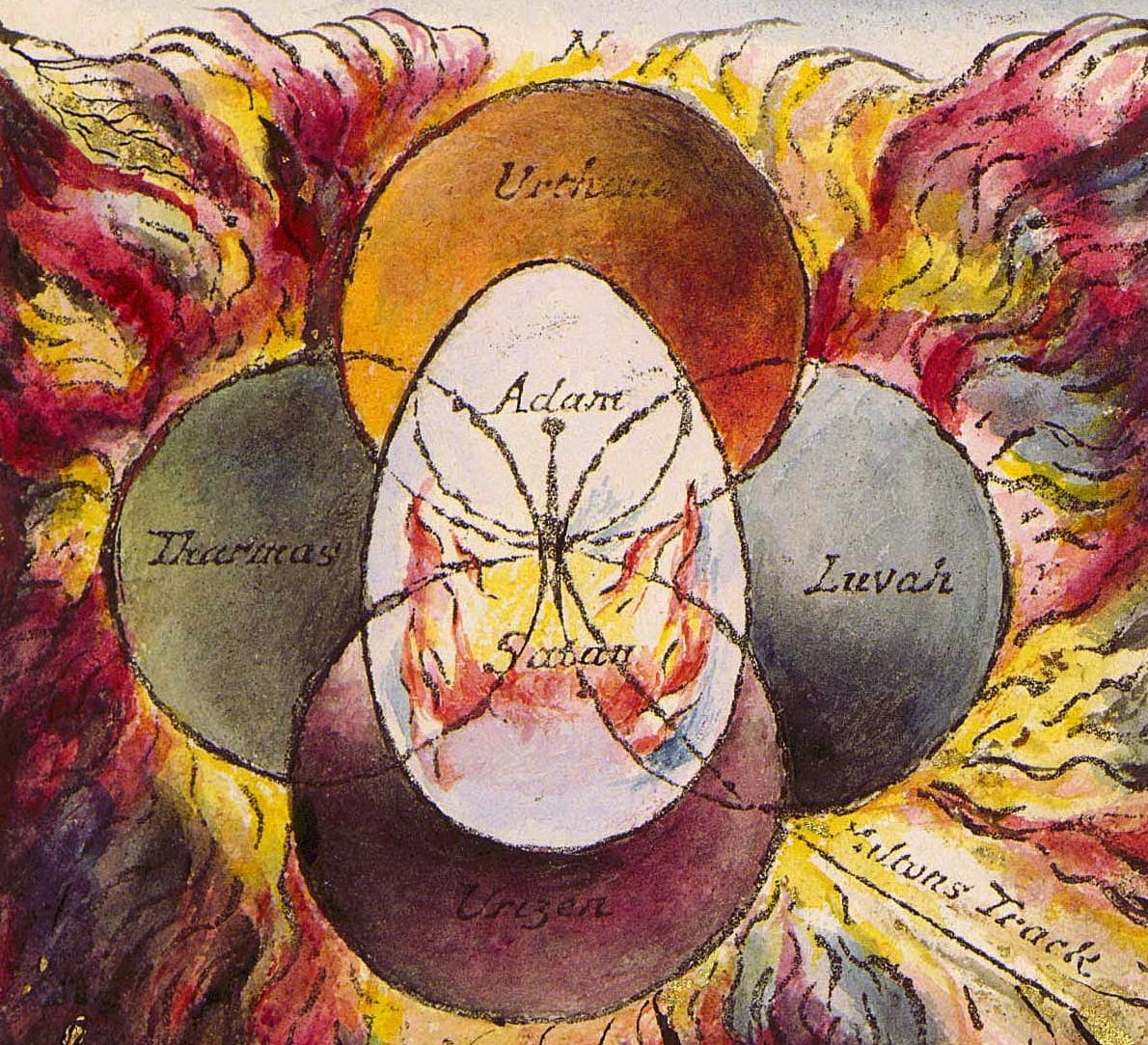

Over the weekend I picked up a used copy of the bricklike Penguin Classics edition of William Blake’s Complete Poems, and I’ve been looking through them for the last few days. I’m less of a Blake appreciator than you might think given my tastes-I’ve known the paintings and the early poetry, especially Songs of Innocence and Experience for a long, long time, but I’ve never really dug into the prophetic books until now.1 Blake’s longer works are famously ordered by a mysterious, insistent personal mythology, little of which is apparent to the first-time reader outside of the strange names which proliferate throughout his corpus. Northrop Frye is waiting in the wings to set me straight whenever I give in, but it seemed only right to try to make a solo attempt at first! Blake and Joyce seem to me Gemini in certain respects, the opening and closing of a circle, or so I might say but that I don’t like closed circles. More on that another time.

Recently I’ve been perusing the political works of the great philosopher Al-Farabi as part of my broader investigation of Straussian thinking. Thus far I’ve gotten to his Philosophy of Plato and Aristotle and his commentary/summary of Plato’s Laws.2 It’s interesting, although my ability to summarize is limited here and I can tell that I’ll have to reread at some later point.

For he who sets out to inquire ought to be innately equipped for the theoretical sciences—that is, fulfill the conditions prescribed by Plato in the Republic: he should excel in comprehending and conceiving that which is essential. Moreover, he should have good memory and be able to endure the toil of study. He should love truthfulness and truthful people, and justice and just people; and 45 not be headstrong or a wrangler about what he desires. He should not be gluttonous for food and drink, and should by natural disposition disdain the appetites, the dirhem, the dinar, and the like. He should be high-minded and avoid what is considered dis-graceful. He should be pious, yield easily to goodness and justice, and be stubborn in yielding to evil and injustice. And he should be strongly determined in favor of the right thing. Moreover, he should be brought up according to laws and habits that resemble his innate disposition. He should have sound conviction about the opinions of the religion in which he is reared, hold fast to the virtuous acts in his religion, and not forsake all or most of them.

Furthermore, he should hold fast to the generally accepted virtues and not forsake the generally accepted noble acts. For if a youth is such, and then sets out to study philosophy and learns it, it is possible that he will not become a counterfeit or a vain or a false philosopher.

It’s tempting to argue that a simple overview of Leo Strauss’s thought would be that he uses some of the insights of Nietzche, Heidegger and Bergson to animate in modernity a political-philosophical vision that one finds in a late antique Islamic context in the works of Al-Farabi. On the other hand, aren’t I reading Al-Farabi in the translation of two students of Strauss? One does wonder if the typical Straussian tendency to read the atheist skepticism of a 20th century European intellectual into the great thinkers of the ages is at play in the choice of text and interpretation. Such is the peril of reading in translation!

An ugly American as President: Warren Ellis’s Transmetropolitan

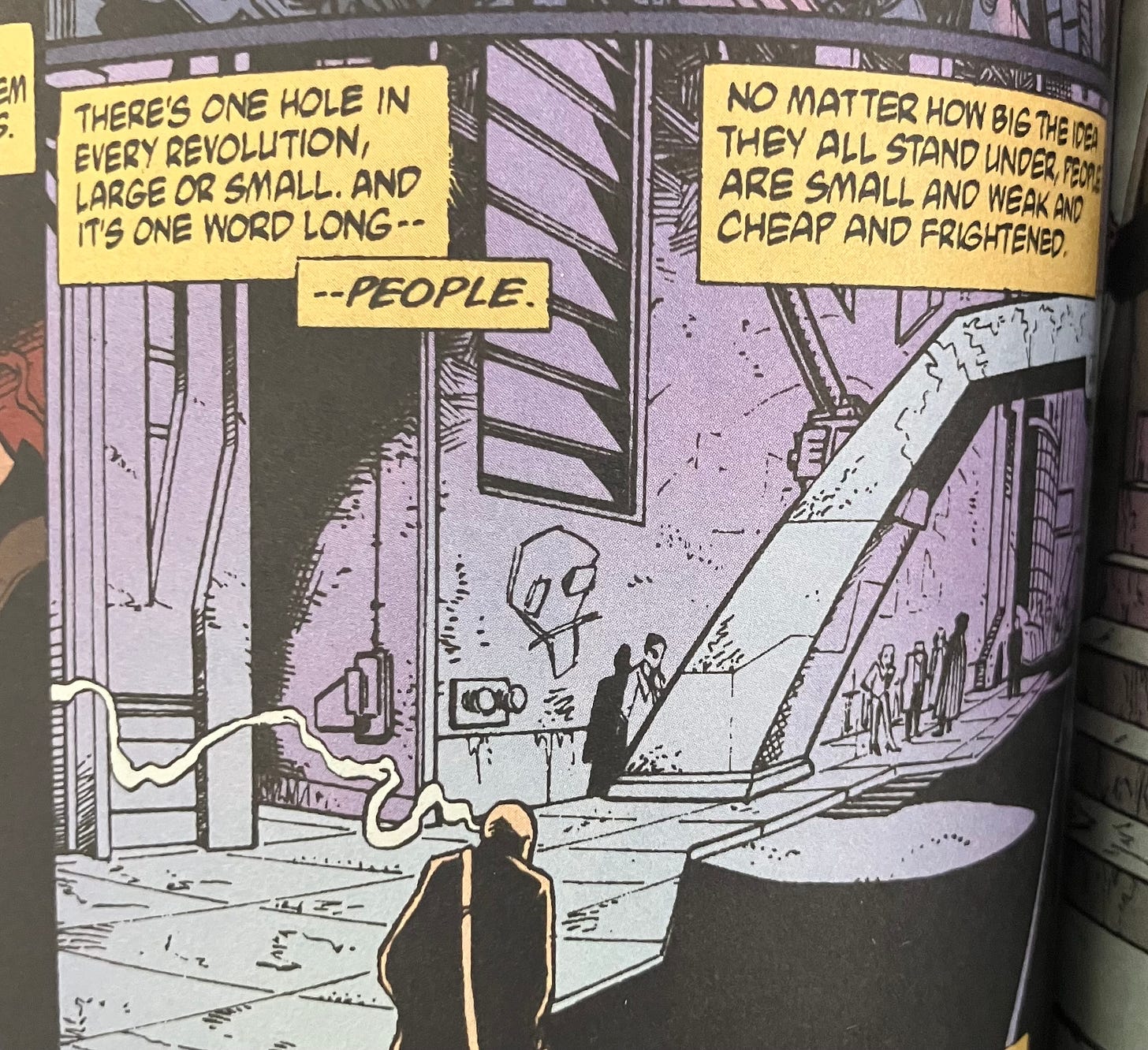

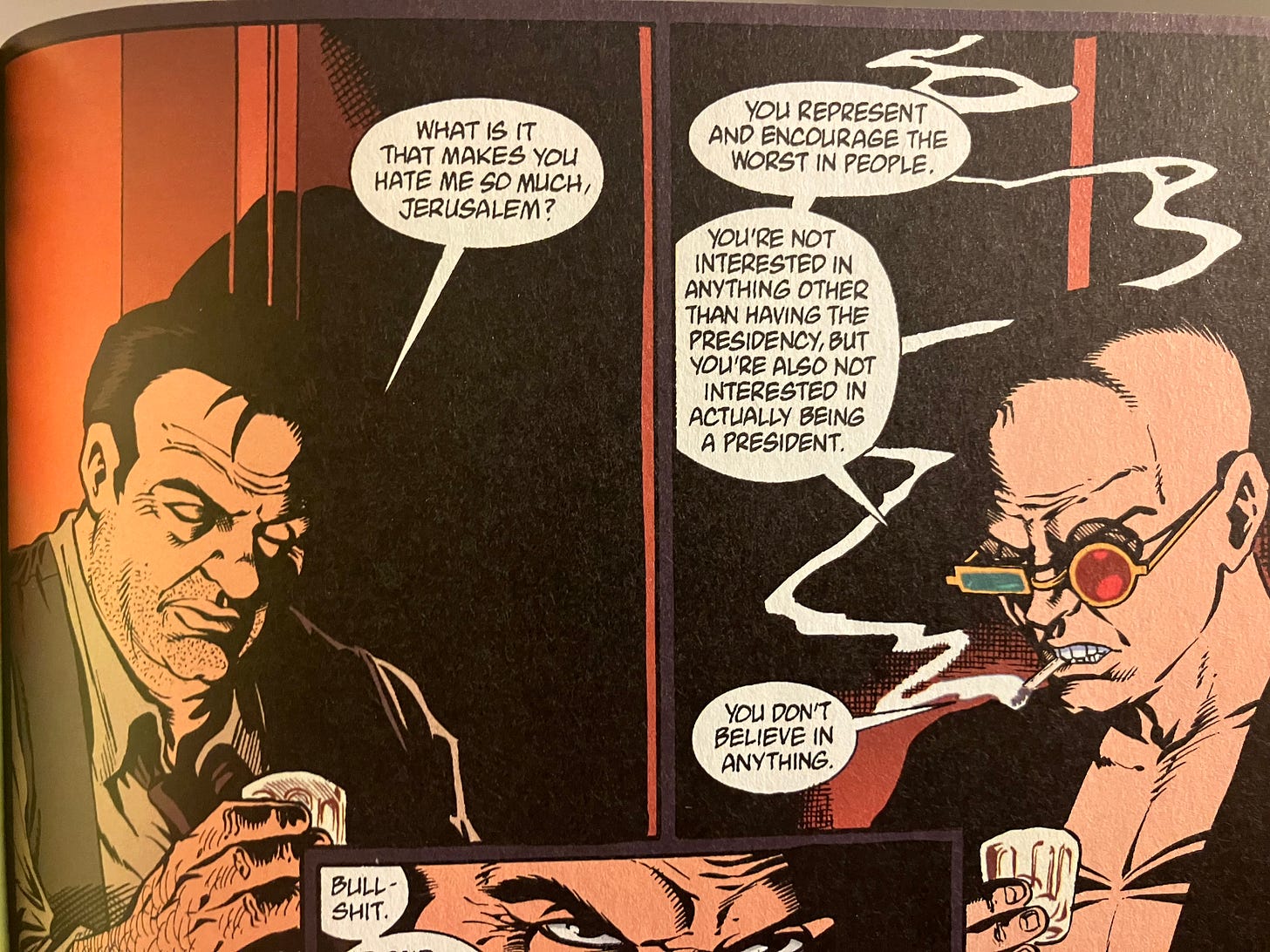

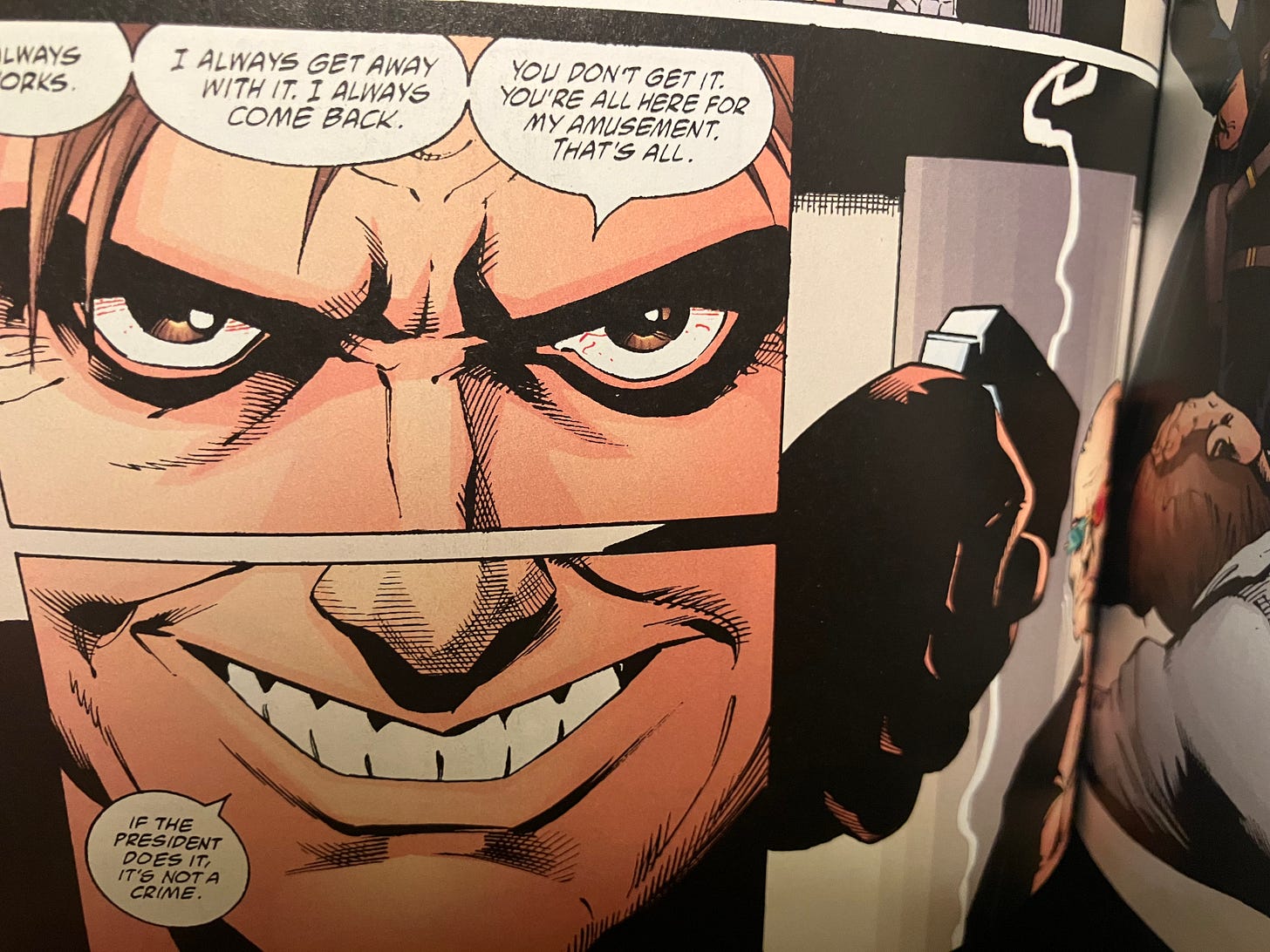

I recently finished reading Warren Ellis’s 1997-2002 cyperpunk comic Transmetropolitan, which had been on my list for a very long time. It’s a decent read, not quite on the level of the other great Vertigo comics of the 80s and 90s, but very much in the same vein.3 Topically, much of the plot of the comic revolves around gonzo journalist Spider Jerusalem’s beef with two successive presidents of the United States during and after a presidential election.4

Does it resonate, does it hold up? Yes and no. Transmetrolitan is very much about a style of journalism that doesn’t really exist anymore, that probably depended in ways that weren’t apparent in the twentieth century on the epistemic certainty of the regimes it fulminated against. There’s a very pure, very righteous, very post-Woodward & Bernstein belief in the power of a story, in the liberation of the Truth with a capital “T” in Transmetropolitan, which at this late date seems to many of us as remarkable as the vision of an angel appearing to a middle aged Meccan and telling him “Read!” or the incarnate logos striding across the surface of the Sea of Galilee.5 A bit like The Sandman this one is also tainted by allegations about Ellis-Spider’s dynamic with his “filthy assistants” probably plays differently than it would have when first published, but it is a fun read nonetheless. Politically Transmetropolitan is very much of the Clinton/Blair/Bush II era: the overall villain the Smiler is a caricature of the grinning third-way centrist or “compassionate conservative” (although he is implied to be a democrat) while the politics of this century have been characterized by a retreat into the “real” and a frank embrace of ugliness and venality as a political virtue.

Late antique religious textblogging

I’ve been revisiting the Corpus Hermeticum lately, a group of enigmatic Greco-Egyptian texts which have been wildly influential on various traditions esoteric and exoteric since late antiquity, considered the oldest of the ancient knowledge, the source or a supplement to Plato and Moses. Since the seventeenth century it has been established that they are in fact Roman-era texts, antique forgeries, etc.6 I’ll spare you the diatribe about gnosticism for now, although it is coming, but I’ve long suspected that the philosophical Hermetica are a better fit for the kind of paranoid James Lindsay-esque efforts to argue that the Promethian ambitions of modernity emerge from late antique heresy than the actual Gnostic texts.7 There’s a famous book about the hermetic Hegel that I’ve read the introduction to but never finished, I might get back to you about that at some point.

Over the last two weeks I’ve read the Quran for the first time, mostly in the 1950s translation by N.J. Dawood published by Penguin Classics, but with the intention of rereading the more recent translation by M.A.S. Abdel Haleem at some point in the future. I have some sympathy for the notion that in a broad brush, history of ideas sense the only account of the West that makes sense as something other than a mere metonym for either Christianity or whiteness is the synthesis of the Hellenic and Abrahamic.8 As such the Islamic world has been a major blind spot in my understanding of the west for a very long time, and this seemed the most reasonable place to begin rectifying that deficiency.9 My advisor always said that he found Islam to have a certain elegant simplicity vis a vis the other Abrahamic religions, and this is certainly true of the prose of its central text. The Hebrew Bible and New Testament are both heterogeneous documents that reflect a plurality of visions: the writers of the gospels of John and Mark seem to have interpreted the life of Christ in very different ways, to say nothing of the quilts of authorship that makes up the Genesis narrative or prophets, while the Quran being the work of one voice, has a certain fundamental unity. I found that the Dawood translation definitely shows its age in some places, so the eventual reread will be interesting.

Two major presences in my nonacademic intellectual formation were Blake devotees, albeit in very different ways. Alan Moore very consciously invokes the master throughout his corpus, and has a similarly tormented relationship with the female body, while Elizabeth Sandifer utilizes them both in very different ways.

I never got around to writing it up, but I read the Laws this summer. It’s a text that you really probably only need to get to if you’re very interested in Plato as a moralist or studying the Platonic reception in later monotheism. It’s very long and very dull, excepting the book about the soul toward the end. On the other hand, because of a strong familial resemblance in both content and form to the legalistic books of the Pentateuch, it was an invaluable text for monotheist readers of Plato in the Middle Ages.

The review of From Hell is still coming, promise!

One tells oneself that it can’t be much worse than the first term, in the full knowledge that it can. I do agree with Ross Barkan that fascism as such is unlikely, that the structure of American government and the patterns of American life would seem to militate against such a possibility, but one doesn’t have to be Hitler or Mussolini to do damage, and I’m genuinely fearful for a number of communities. These concerns are entirely compatible with a sense of more or less agreement with what John Ganz argues here:

I believe all Trump’s power grabs, like January 6, are likely to fail and be farcical, as is the very notion of Trump playing Caesar. But he very much wants to play that role.

I do suspect the most likely outcomes of a second Trump presidency are worsening government function and a significant acceleration of what one of the prominent theorists of the movement, the late Angelo Codevilla referred to as “cold civil war.” Increased hostility between federal and state authorities of the sort that characterized the pandemic or the Texas/Biden standoff last year. Still, one shouldn’t pretend that the worst is off the table. All that said, I would not expect a stream of up to the minute punditry from this blog. My politics are too boring and I’m not qualified to be interesting about events or ideologies less than twenty years old. There may well be political murmuring in the next few weeks, but I’m working it out of my system.

I am still reading William Gaddis’s The Recognitions. It’s probably the closest American equivalent to Ulysses-I don’t quite understand what Franzen meant when he said it was the most difficult book he’s ever read, but it is intimidating, significantly more allusive than Joyce and very long. Gaddis is a type we don’t produce in huge numbers but you get to know all the same studying American letters: cynical and embittered in a way that masks a deep grief about everything solid melting into the air of capitalism’s nation, a mourning for the vanished-seeming unitary Deity on Whom all things depend. Like Pynchon he works it a bit thick and the characterization leaves something to be desired much of the time, but it’s quite a read.

The Franco-English philologist who made this discovery was the namesake of the pedantic scholar Edward Casaubon in Middlemarch.

I need to brush up on the vein of 20th century exilic German scholarship that this emerged out of before I write much else, but I’ve long disagreed with the Eric Voegelin thesis about Gnosticism, at least in terms of the actual textual traditions that re-emerged from the sands in the 20th century. There is another gnosticism, one that lived for millennia in the writings of the heresiologists, that I tend to regard as the shadow of all that Christianity repressed to become an imperial religion, and this is probably closer to the money.

I get this framework from a (sadly paywalled) 2017 episode of the Secret History of Western Esotericism podcast featuring the scholar Matthew Melvin-Koushki.

The specialty of my academic, and later thesis advisor in undergrad was the history of U.S./Middle East relations. His mantra was that we as Americans don’t really understand the Arab world, and our lack of understanding has lead us into catastrophic blunder after catastrophic blunder in that region. Needless to say I’ve often found myself wondering what he makes of the events of the last year or so.

Oh, I read that. You mean the book by Graham Alexander Magee

Great post! You write that Transmetropolitan is “not quite on the level of the other great Vertigo comics of the 80s and 90s, but very much in the same vein.” What would you consider the great Vertigo comics? I’m currently reading and really enjoying The Invisibles, and I’ve read From Hell and The Sandman, but outside the Moore/Gaiman/Morrison trio I’m totally ignorant.