Hi! In the last two weeks I uploaded a short essay about spirituality in the 2020s. It came out pretty well, although

and both made some insightful observations/corrections. Some essays seem to come almost entirely unwilled, as though they were waiting in some higher reality to impose themselves upon us. I found the first volume of My Struggle and an old penguin copy of Lucretius, and the rest just flowed over the next few days. on Wednesday I followed it with a somewhat rambling appraisal of the contemporary rightward turn in the life of the mind, one that was somewhat more like these digests than is usual. People seemed to like both, and I imagine I’ll be doing more writing like that in the coming year.Ann Douglas, Calvinism & cultural feminization

I mentioned that I’ve been reading Ann Douglas’s The Feminization of American Culture for the last few weeks. It’s a fascinating book, and a strange one in some ways. If anything it reminded me most (as I think I said at the time) of Richard Hofstadter and early Christopher Lasch. It’s largely about the shifting theology and sociology of New England Calvinism as it became something much more easygoing and resigned to American society as it became ever more secular and sentimental. In effect Douglass argues that as religion softened ministers found themselves increasingly in the same boat socially as middle class women, excluded from the Victorian model of masculine worldliness. As such both parties collaborated in a sentimentalization of American society that Douglas views as ancestral to the mass culture of her own century.

The modern historian, with the easy advantage of hindsight, can see the line of thought which contemporary clerical writers were barely beginning to enunciate. Beneath the conjunction of femininity and Christianity lies a probably unacknowledged assumption that the modern age in some sense would belong to the woman; and hence, hopefully, to the minister who accommodates and imitates her. Indeed, whether or not clerical observers fully knew it, the middle-class woman's place in the emerging industrial order was assured; if neither autonomous nor respected, she would be, at the least, its most carefully watched, skillfully programmed, and rewarded victim. In espousing feminine values, the minister could become a middle-man of history, a participant, or a puppet with his feminine peers in the rather cowardly new world of consumer culture.1 The historical rationale, no matter what its validity, no matter how fully it exculpates the woman and the woman-bound minister and releases them from the impossible task of self-judgment, leaves two absolutely critical questions unanswered: where will the process of feminization, and fictionalization, stop? And whose interests does it ultimately serve?2

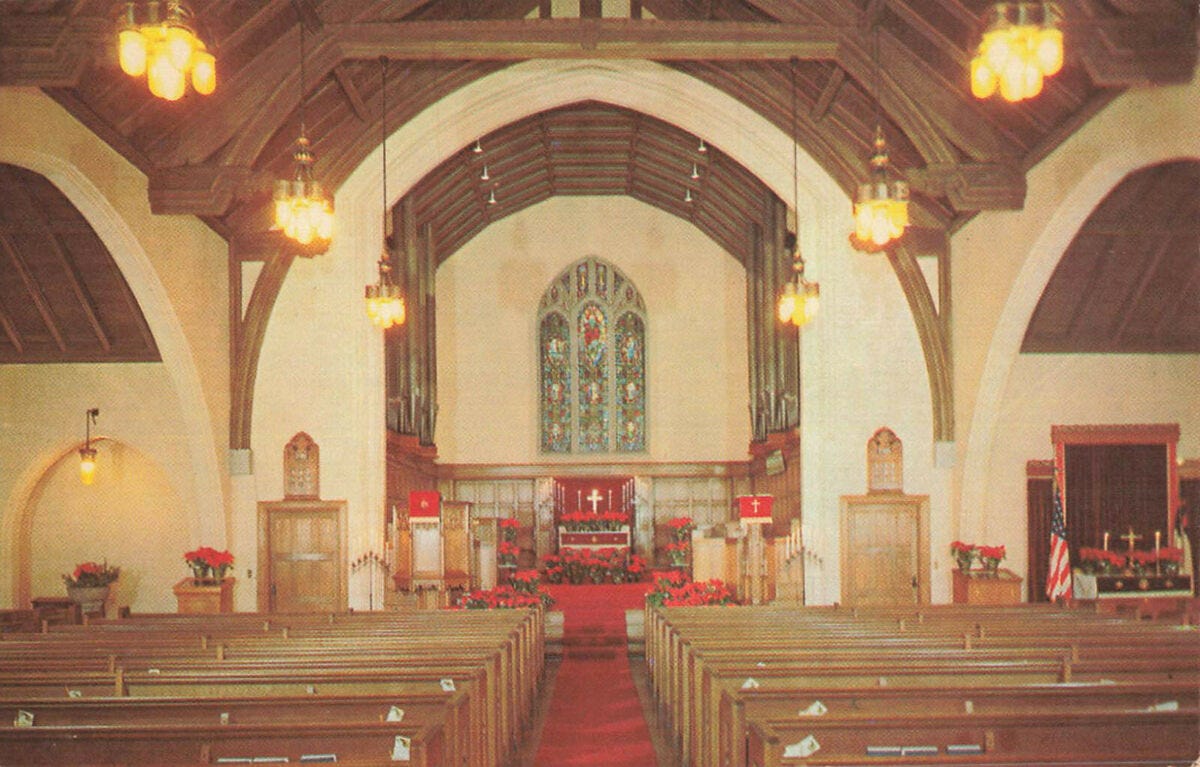

It was interesting to read considering that the church I grew up in-to the extent that I grew up in church-was descended from both the Calvinism Douglas mourns and the liberal congregationalism she demeans. Indeed I feel looking back that Calvinism was somehow the substrate of my childhood and adolescence, that in some ways although vanquished in the pulpit the efflorescence of the puritan vigor lingered in the forests of New England all the same. The idea that you needed to be industrious, that your worth was defined by how much of a motor you had in you, the self doubt, the sense that the world was cruel, that nothing was to be counted on, and that it was always possible for God to reject you, even if it wasn’t put in quite those terms nonetheless left an indelible impact on my psyche. I am sometimes told that I have a predilection toward the dramatic, and I wonder if that isn’t connected to this.

In the older Calvinist scheme to us and hopefully visale others were not, and the difference was a momentous and hopefully visible one. God's ways were both unknowable and exact; momentously, one person was taken, another was left, although the why of it might not be clear. There was an immense incentive for thought-filled precision in this creed with its imperious and legalistic Atonement. Repressive as it was, Calvinism was empirical, even scientific, in the special objectivity it fostered and demanded in its most faithful believers. If God had few soft spots in his heart, little sympathy for man, the good minister owed it to his flock to be equally harsh, equally factual, and equally determinate. The only antidote for divine wrath at a clergyman's disposal was ministerial wrath; the only immunity to punishment was in its anticipation. Calvinism could give to those who believed it a confidence, which at times merged unpleasantly with arrogance, that they were at least fully armed, if not invulnerable.

There is a certain type of conservative or reactionary who regards the American Victorian era as a sort of lost national paradise, an age of virtue when government was small, Christian morality was in effect, and men and women knew their places. Christopher Lasch comes to mind here, as does Harry Jaffa and his various intellectual progeny. There are some grounds it is true, for regarding the first half of the century as an American age of heroes, when giantlike statesmen and heroic radicals strode the earth, but when one reads a text like Douglas’s (or in a more English, more literary sense Nancy Armstrong’s Desire and Domestic Fiction) one gets a rather different picture of the period!

The Philosopher as Historian: a Preview

I recently finished a very lengthy reading of Harry Jaffa’s A New Birth of Freedom: Abraham Lincoln and the Coming of the Civil War, his reappraisal of the political-philosophical issues at stake in the American Civil War and the role of Lincoln. The second part in an ultimately unfinished trilogy, it consists of the final word of the mature (he was 82 years old on publication in 2000) Jaffa on the American founding. The middle aged Jaffa who wrote the magesterial Crisis of the House Divided was a basically faithful Struassian, perhaps a bit heterodox in places but sticking basically to the position laid down by Strauss that ancient political philosophy was superior to the modern, and that America while good, is a fundamentally modern regime. His interest in Thomism perhaps set him apart, but otherwise he was one of several students of Strauss interested in a serious way in how what they had learned from their teacher could be applied to the structure of American government and history. In Crisis the American founding is thus presented as flawed because modern and faithful to John Locke, a thinker of whom Leo Strauss had a very heterodox reading.3 For the younger Jaffa Lincoln is a providential figure who corrects the founding, a near demigod who devises a new formulation of the American political order.

Yet despite the consistency of Lincoln's alternative rendering of the signers' and Founders' meaning, it cannot be endorsed on historical grounds without some qualification. For in the passages just quoted Lincoln treats the proposition that "all men are created equal" as a transcendental goal and not as the immanent and effective basis of actual political right. And, in so doing, he transforms and transcends the original meaning of that proposi-tion, although he does not destroy it. His, we might say, is a creative interpretation, a subtle preparation for the "new birth of freedom."

Of course the Jaffa who wrote this was not yet a conservative in the sense he would be later on, and this interpretation of Lincoln is in some respects not terribly unlike that made by figures on the right considerably more hostile to the 16th president. Whatever the cause, in the years following Strauss’s death Jaffa wildly revised his interpretation of the American founding, and this is borne out in A New Birth, most notably in its lengthy second chapter, a sweeping sketch of western history from the fall of the western Roman Empire to the signing of the constitution. For the late Jaffa America is both perfectly classical and modern, a near-providential empire of liberty . If nothing else this book made me realize how little I actually remember of what I’ve read by the founders, something I need for several reasons to rectify.

As I've remarked elsewhere, Jaffa is a very easy figute to both admire and somewhat loathe. His conviction that equality was a conservative value and love of America, the defenses of civil rights one finds in his late work-these are positive and truly a breath of fresh air within the fearful and indeed often neo-confederate atmosphere of postwar movement conservatism.

Within the American political tradition, Lincoln transmutes the latter-day immigrants from the ethnically divided nations of the Old World into members of the same family, united by the transcendent faith in human equality. That faith is the faith of the same ancestral "fathers" he will celebrate in the Gettysburg Address. Indeed, in saying that they are of the same flesh and the same blood, he uses the very idiom of transubstantiation.

On the other hand there is much in Jaffa that was brittle, shrill and dogmatic.4 His was a system in which no one stone could be mislaid lest the entire edifice collapse into nihilism and horror, and thus he often seemed interested only in the classical America, in the marble edifice of the new Rome on the Potomac, rather than in the oddball or marginal, the magic and dread which characterizes so much of our culture at its best. It does seem to me true what one rival Wilmoore Kendal argued in response to Crisis, that there was a kind of latent Caesarism lying below the surface of Jaffa's love of Lincoln, although I’ll discuss that more at a later date. In any case both his books on Lincoln are well worthy your time, although Crisis of the House Divided is really the one to read if you’ve never dipped your toes into his work. By the end of its four hundred pages he’s just about converted you to his premise, which I can't say is true of A New Birth of Freedom. There are some very fine sections of the book, and it was an enlightening read in many ways, but the style becomes somewhat of an acquired taste, being at points it must be said really just beyond parody.5

As with Lasch, it’s not always clear what sort of world Douglas would prefer: she doesn’t seem as some of her academic contemporaries would to chide her subjects for not ditching their bibles to get hip to what was being written in the British Library during those same years, but she does have a strong sense that this feminized civilization was cowardly, weak, less honorable than the uncompromising and manly Puritanism that it replaced .

I think it’s generally healthy to question the will to power of moralists of all stripes, although as I am always tiresomely saying, you can go too far with this maneuver. At a certain point seeing the rot inherent in everything can be an alibi for never changing— for good or for ill.

I recognize how incomprehensible this is if you’re unfamiliar with Strauss, and so plan on writing a short and inevitably inadequate prolegomena on him as he is generally understood by sympathetic if not fully esoteric readers and especially Natural Right and History before I really engage with Jaffa and the Claremont school next year.

I find it curious that Glenn Ellmers’ recent book on Jaffa’s thought largely elides his holistically philosophical rejection of homosexuality as valid or normative given that it’s my understanding that liberal tolerance of traditionally non-normative sexual proclivities and identities is fairly central to the west coast Straussian gripe with modern America. This is especially odd given that the center of gravity of the tradition as a whole has shifted from California to Hillsdale and from neocon to evangelical Christian, and the book is not written with an unsympathetic audience in mind.

I wrote “sentimental great man kitsch” in the margin over one particularly florid comparison.

interesting stuff.

I love reading your stuff because it comes from a point of view and tradition that I know fuck all about. So keep it coming.