Philo-Aesthetic digest 12/29/2024

Broken Clocks, Cantos, Invisible Bridges, Election takes, year end shout outs & the Book of Revelation

Hi! I was going to write one of those Substack year end review things and then I was going to write up a weekly digest, but in the end I would up combining them. Enjoy!

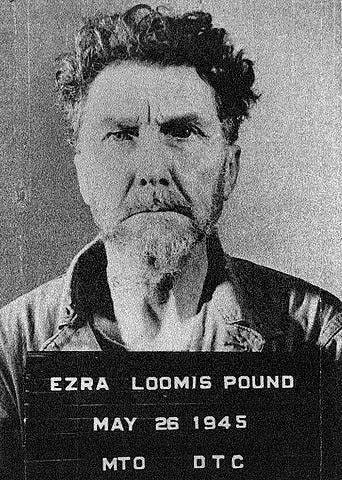

Capsule overview: the Pisan Cantos

My understanding is that most people do not read Ezra Pound’s Cantos at all, but if they do, the choicest cut seems to be the Pisan Cantos, published in 1948 and largely written while imprisoned for treason and then incarcerated as a madman in St Elizabeth’s in Washington. Of the high modernist works I have read, even if only stumbling through, wandering the streets the way that Borges said he wandered through Ulysses, The Cantos are by a long shot the most difficult, the least comprehensible unaided by annotation. Written in a smattering of languages, only two of which I have any fluency in, Pound’s poem approaches outsider art in its repetitive refrain to the economic theories that utterly consumed its creator over the course of the second half of his life and led him toward fascism and antisemitism.1 I think having some grasp of the (primarily Chinese) ancient philosophy he was playing with is almost more important than the languages, although not knowing them leaves the poem something of a wreck, a disaster because you can only crudely or not at all sound out how it fits together. In justifying why he won’t read it during the episode of his increasingly essential Invisible college podcast dedicated to Pound

described the Cantos as something along the lines of “Ulysses if the references to Spinoza and contemporary Irish politics were all there was to it”, and there’s definitely something to that.Broken Clocks and Conspiracies, Invisible bridges and dispensations

While I didn’t exactly predict it, I wasn't hugely surprised by the outcome of this year’s presidential election.2 This was in large part because during the summer I read one book and reread another that painted pictures of two periods in American history not unlike our own. The first of these was

’s When the Clock BrokeA notable recent entry in what

, on whose nonexistent blog I should really be a regular commenter rather than the other way around called the “bestiary of the right” school of intellectual history (don’t laugh, it’s basically what I do too) When The Clock Broke chronicles the election of 1992 and the general malaise of the early 1990s in America, lean and discontented years in which the appeal of the normative right and left seemed to falter and for a brief moment it appeared that a new synthesis would break through. Ganz insightfully sketches out the intellectual lineages and initial manifestations of this phenomenon, helpfully situating it in the context of the changed right in the aftermath of victory in the Cold War.The sudden end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union made everything worse. Militant anti-communism had long provided the glue that bound the various factions of the right together and gave them common purpose.3 The loss of the USSR was so traumatic that the John Birch Society went into full-blown denial: they insisted that the breakup of the Soviet Union was a KGB ploy to get the West to drop its guard. Who was to be the main enemy now?

Many parts of the book seem remarkably prescient, but especially the chapters chronicling the state of New York City in the early 1990s, entitled “The Mosaic.” Chronicling racial woes, the early career of Rudy Giuliani, Sam Francis’s exegesis of The Godfather and John Gotti’s rise as a Robin Hood figure in the eyes of the city, it’s quite a read.

When New York turned its lonely eyes to John Gotti, it was longing for another kind of authority than the type Giuliani had represented up to that point. It didn't really want the law, universalism, meritocracy, rationality, bu-reaucracy, good government, reform, blind justice, and all that bullshit.

The institutions had failed, the welfare state had failed, the markets had failed, there was no justice, just rackets and mobs: the crowd didn't want the G-man dutifully following the rules, and it didn't want to be part of the "gorgeous mosaic", it wanted protection, a godfather, a boss, just like the undertaker at the beginning of The Godfather. Gotti was not really a figure of revolt and anarchy at all, he was a symbol of order, the old order that many longed for still, an order more real and deeper than the law, upheld by brute power.

What I took to be the largely unspoken thesis of the book, brilliantly left mostly unstated until the jaw dropping, punchline-like conclusion-reminiscent in some ways of the trick Roth pulls in Portnoy’s Complaint-is that twenty-four years later those energies would recur and the synthesis promised by Pat Buchanan and David Duke, by Murray Rothbard, Sam Francis and Ross Perot would be made flesh in the campaign and then presidency of one Donald J. Trump.

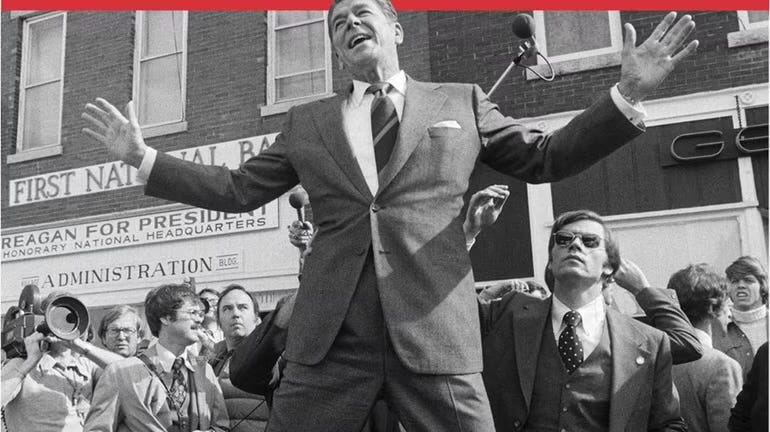

Rick Perlstein’s The Invisible Bridge: The fall of Nixon and the Rise of Reagan is a book I first read years ago as an undergraduate, but that I felt compelled to revisit in late spring, picking up a copy to reread the week before Biden’s disastrous performance in debate with Donald Trump which would ultimately scupper his reelection bid. The tetralogy in which The Invisible Bridge is the third part covers the postwar right and American culture writ large from Goldwater’s loss to Reagan’s victory in 1980. Perlstein is a writer I admire deeply, and these books are among the best popular histories I’ve read, replete with an enormous amount of detail that captures the feeling of what one imagines it was like to experience the period in question. I recommend them highly to anyone who hasn’t already looked into them.

The reason I returned to it was that I was beginning to get the feeling that the world and the cultural environment we’ve been living in since early 2021 reminded me of reading Perlstein, and particularly this volume, which covers roughly the term which Nixon won in 1972 and then was forced to relinquish to Gerald Ford. The America described by The Invisible Bridge feels very familiar, full of malaise and decay and poised on the brink of several possible new births. The general thesis Perlstein advances is that we eventually made the wrong choice, choosing the edifying stories peddled by Ronald Reagan (whose unsuccessful attempt to primary Gerald Ford in 1976 is the major narrative of the book) over hard, grimy truths which would have required real sacrifice and reckoning with who we are as a nation. The first time I read this book I agreed wholeheartedly with this thesis. Now I’m a little more circumspect, less because I disagree with Perlstein’s account and more because I’m less certain than I was then that we should do away with stories, or even that we could even if we wanted to.

The Biden interregnum feels very much like a chipmunk-speed replay of the Ford and Carter administrations, two presidencies defined-although neither was helped by various internal errors and incompetences, as well as events outside of the control of any one executive-by entering office with what was fundamentally an impossible mandate to heal a wounded nation.4 Consequently each found himself unceremoniously ejected from the oval office after a single term, and so it has turned out for Joe Biden. I kept my mouth shut mostly in the cycle, mulled over doing a meditation on the whole "weird" attack sometime in August but ultimately couldn't get the hook just right, which in the end probably saved me a lot of grief and public embarrassment.

My study of American history over the years and more recently my reading this summer of Richard Hofstadter, Francis Fukuyama, and a Mark Lila book I didn't end up writing about has tended to leave me with the impression that American history is a kind of punctuated equilibrium in which short prophetic attempts to "achieve our Country" as Richard Rorty once put it, break up long periods of agreeing to disagree about the human rights of various members of the nation. Going into this election I had the uneasy sense that we were headed back into such a period of deciding that the groceries are more important than people's rights, as has tended to be the pattern after era/s of upheaval such as the one we just lived through in the 2010s.5 The mistake I made, which I see all to clearly in hindsight was that I assumed people were finally sick of trump, and a Biden or Harris victory would lead to a normalization of Cold Civil war, a new dispensation of agreeing to disagree about reproductive and electoral rights, rather than the voters spinning the roulette wheel for Trump in the hopes that he could somehow make it 2019 and 1980 again. It’s a strange thing to have read the tea leaves correctly but in the wrong direction, lacking either the finality and closure of a proper miss or the vindication of having known the score from the start.

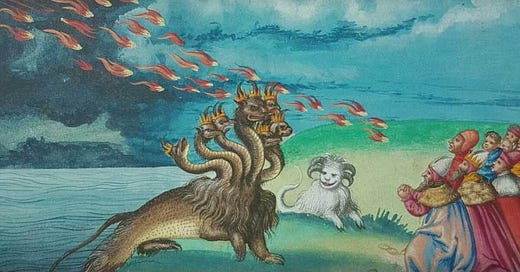

Behold I make all things new: the Book of Revelation

I recently reread the Apocalypse of John which ends the New Testament, this time in the King James Version. I think most of the times I’ve read through the book it’s been in the KJV, although I know I’ve done the RSV at least once, and I do tend to favor that translation for personal use.6 In any case I’d recommend the KJV for Revelation, a vivid, bewildering, and frequently terrifying work which benefits from that most literary of English translations.

And I saw an angel standing in the sun; and he cried with a loud voice, saying to all the fowls that fly in the midst of heaven, "Come and gather yourselves together unto the supper of the great God;

The task of interpreting the Johanine apocalypse is a notoriously difficult one, and I’ve largely tended to view myself as unqualified to try. I’m tempted to go so far as to say “therein lies madness” but that might be both a little too dramatic and borderline blasphemous. I think there is some scholarly consensus that the Beast rising from the sea is meant to represent Rome, and that John of Patmos seems not to have had a very high opinion of the Greco-Roman world, but these things are like everything else subject to disagreement.

The New Testament is both an inspiring work, the Good News as the expression goes, and absolutely terrifying work, and nowhere is that more evident than in its final book. One of the failings of Christianity in our time, and possibly in others as well, although it’s hard to judge what one has not experienced, is failing to maintain that tension. Christianity seems either so easygoing that people don’t go to church at all, or so much about shutting the gate, about the perfect hatred of God for those that He created only to burn in the eternal fire to glorify His power. Some middle ground must be possible, although it is possible also that what is said of the church of the Laodiceans could also be said of me.

I know thy works, that thou art neither cold nor hot: I would thou wert cold or hot.

So then because thou art luke-warm, and neither cold nor hot, I will I spue thee out of my mouth.

People and blogs I want to shout out before year’s end who I didn’t mention in the body of the post

’s To Live is to Maneuver became a new favorite blog this year, insightful commentary on the history of the American right from a genuine scholar of the topic.’s Woman of Letters has been an insightful and entertaining read from week to week-check out her novel too! What I love about Naomi is how frank her writing is about so much that people are so romantic about in the literary-cultural sphere. I look forward to reading her upcoming book on the Great Books.’s Notebook, is always an interesting and thoughtful read.’s Eminent Americans podcast and blog, home to engaging and informative surveys of the contemporary intellectual world.’s A Good Hard Stare offers a fascinating mix of observations on art and literature classic and contemporary. Reading him over the last year has been enlightening! publication of the same name does interesting work somewhat similar to mine in terms of politics.Likewise I would recommend

’s The Extremely Difficult Realization and ’s Interruptions to anyone who likes the more spiritual and searching side of this blog.’s The Parish Bulletin-wonderful thoughts on faith and culture, a very underrated commentator on the world we live in today.’s Life and Letters has been consistently stimulating, with many insightful observations’s Invisible Head’s A Stylist Submits’s Ashes and Sparks…And many more I promise I’m omitting out of ignorance and poor memory rather than malice or disdain. I have so enjoyed reading and discoursing with all of you over the course of 2024, have a very happy new year!

As I remarked last time he came up, the particular way that Pound’s antisemitism functioned-that he very systemically viewed modernity as the world the Jewish people had created for themselves at the expense of everyone else-reminds me a great deal of contemporary anti trans rhetoric in the flavor one gets from someone like Wesley Yang. For a while last year I modified a line from Andrea Chu to express this-”in post or late modernity everyone is trans and everyone hates it.” I eventually stopped doing this because I found that people interpreted the statement in the assertively positive way that ALC meant her original phrase in Females, while I intended something much more ambiguous-to negative. As Socrates found out in Athens, it's a very dangerous thing to be the person or persons the multitude hangs its discontent on.

Among other things there were enough epistemically shattering events this year that I felt perfectly comfortable telling people that I had very little idea what was going to happen.

There is a view among this sphere of scholarly inquiry that has come to prominence over the last decade which stresses the continuity between the more Neo-confederate, fash-curious right of the pre-Second World War era and the Buckleyite movement conservatism that predominated between the 1950s and 2000s.

It occurs to me that a characteristic Biden shares with Ford and Carter is taking the fall for the foreign policy blunders of multiple successive predecessors in the Oval Office. The public response to the fall of Saigon in 1975-a largely foregone conclusion to an unpopular war-rhyme in many ways with the response to the fall of Kabul. I remember thinking in August of 2021 that regardless of wether it was Biden or not the Dems had probably just lost the next presidential election because the sort of media liberal who hated Trump in his first term for making America look weak and corrupt would turn on them, and this was more or less borne out in certain ways in the 2024 race.

I know that some of you who have read your Christopher Lasch and Ann Douglas will say that the prophetic periods are only ever a mask for elite will to power and self interest, but I say that even if it’s true some of the time, this is a little too cynical.

When I start doing paid posts sometime in the new year I anticipate one of the first being an explication of my somewhat idiosyncratic and primarily aesthetic preferences with regard to bible translations.

Thank you very much! It’s always interesting to me where our intuitions overlap and diverge! Just the other day, I was thinking of reading the Book of Revelations! Now, if I believed in synchronicities…

One of the religion courses I took...jeez, a decade(?) ago covered Revelation and we spent a few weeks on it. The professor had some fairly radical (by suburban Christian college standards) views and did a lot of developing the beast=Rome analogy, and then capped it off by saying "We (the US) are the new Rome." Always stuck with me. (Also, we read Craig Koester as commentary, if you're looking for a helpful guide.)