Hawthorne and Action: a draft

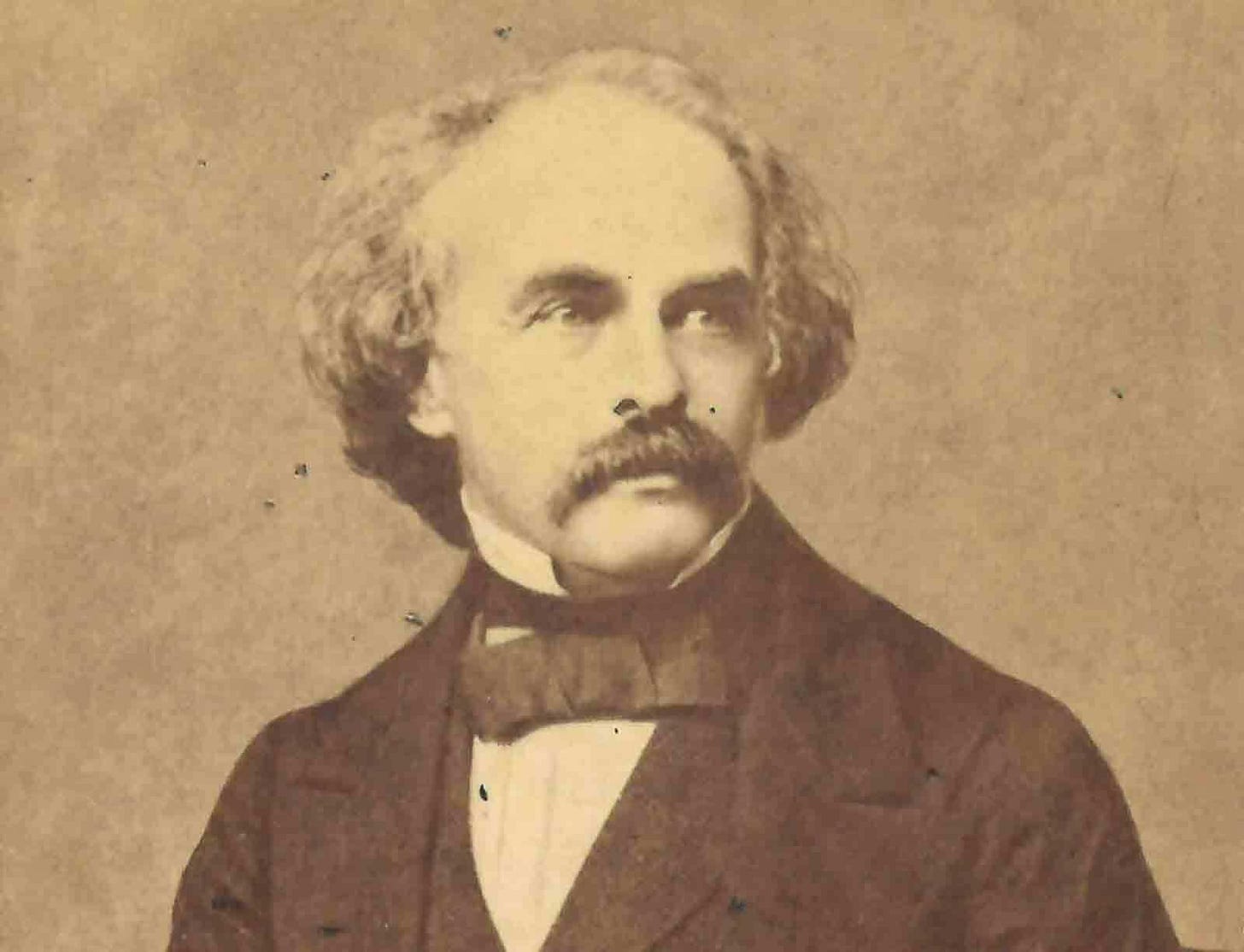

If Nathaniel Hawthorne isn't necessarily the Great American Novelist, he is certainly the first of the type, the proteus shifting between shapes which would be claimed later on as the sole property of this or that successor. Almost every great American novelist is contained within Hawethorne. His major works are essential reading not only for the specialist in American literature, but for the general Americanist who wants to try to understand the fundamental dynamics of this culture. Eventually I want to write a longer piece on Hawthorne's politics, so I won't go as deep into the weeds as I could here, but the gist is that he is the progenitor of both the haunted, backward looking with guilt strand of our culture and a certain smirking rightwardness which scoffs at the idea of betterment for anyone or anything, considering those who hold those views as at best idiots. Put another way, both Beloved and South Park emanate from Hawthorne's craft.

It is one aspect of this inheritance that I wish to consider today, the one that I am most troubled by, which emerged clearly to me last year while I was reading The Blithedale Romance for John Pistelli's Invisible college lecture, although I had been aware of it for some time and had noticed it in other thinkers in the American tradition. I am speaking here of a certain suspicion that action itself is somehow evil, and that the only redemptive thing is the contemplation of the beautiful object. I think this is evident in Lionel Trilling's fence-sitting, in the centrism-conservatism of so many of the great American fictions. I mentioned this in passing to John in reply to his essay of last week, and he pointed me toward Emerson's essay on Goethe in Representative Men, which contains a similar sentiment.

If I were to compare action of a much higher strain with a life of contemplation, I should not venture to pronounce with much confidence in favor of the former. Mankind have such a deep stake in inward illumination, that there is much to be said by the hermit or monk in defence of his life of thought and prayer. A certain partiality, a headiness, and loss of bal-ance, is the tax which all action must pay. Act, if you like, — but you do it at your peril. Men's actions are too strong for them. Show me a man who has acted, and who has not been the victim and slave of his action. What they have done commits and enforces them to do the same again. The first act, which was to be an experiment, becomes a sacrament. The fiery reformer embodies his aspiration in some rite or cove-nant, and he and his friends cleave to the form, and lose the aspiration.

I am uncomfortable with this aesthete's unwillingness to reach out and touch because I see so much of it in myself, and certainly one cannot live this way. One must tell the suicidal friend that life is worth living, one must comfort the grieving, one must act and not simply observe, because at some point the failure to act does become complicity. Hawthorne knew this of course. The Blithedale Romance suggests as much, drawing up a subterranean criticism of the narrating Miles Coverdale, revealed in the closing pages to have possessed a much more central role in the whole affair, to have been much more involved than he lets on. Every time Coverdale fails to act drives a stake further into his own aims and desires. If Hawthorne judges the utopians of Blithedale, and he certainly does, he also casts judgement on his narrator and his failure to aid old Moodie or to save Zenobia. Miles Coverdale is not above it at all, is not the dispassionate observer he makes himself out to have been throughout so much of the narrative. We are ourselves more than observers, even if we be merely scribblers at this or that seemingly futile endeavor.

A scribbler on the president: some futile notes on my attempt to make sense of of it all

I've been a little at a loss about what to say about Trump II, so I haven't really said anything, despite making some gloomy allusion in these digests every week, to the point that I feel like I'm boring you all with politics despite hardly ever mentioning them explicitly. I suppose a little inside baseball is in order. I expected until fairly late in the game that this term would be broadly similar to the end of his first presidency, which was characterized, to the extent that there was an ideology at all, by a shift from populist-paleoconservatism as embodied by Bannon et al to a sort of vulgar west coast Straussianism which closed out the last year or so, and which events such as January 6th were in many ways downstream of. Indeed, while their influence only peaked in the last year or so of that first term, after the normal republicans and the few neocons willing to work in the administration had been driven away, the tenor of the Trump presidency was always in some ways set by west coast Strausianism's sense that between the election of Obama and Obergefell v. Hodges America had reached an inflection point past which it would in some fundamental sense no longer be America in the absence of some dramatic, Caesarist intervention to restore national greatness.1

2016 is the Flight 93 election: charge the cockpit or you die. You may die anyway. You—or the leader of your party—may make it into the cockpit and not know how to fly or land the plane. There are no guarantees.

Except one: if you don’t try, death is certain. To compound the metaphor: a Hillary Clinton presidency is Russian Roulette with a semi-auto. With Trump, at least you can spin the cylinder and take your chances.

Michael Anton, “The Flight 93 Election”

in practice of course this wound up submerged beneath Trump's whims, failing to produce the kind of statesmanship desired by the Claremonsters.

The degree to which this second administration is thus far dominated by a rather different kind of California conservatism-Silicon Valley neoreaction-has been a bit of a surprise. It was clear that project 2025 reflected Yarvinite influence, but it was also pretty much the sort of thing Heritage had been putting in front of GOP presidents since the Reagan era. I’ve read the first two Mandates for Leadership, and while the methods have certainly become more extreme over the years, their goals haven’t really changed as much as you might think. Conservative intellectual wonks have wanted the Department of Ed gone for longer than most of us have been alive. Certainly the veritable co-presidency of Elon Musk has been a surprise as well: it was clear that the reactionary tech moguls were putting their thumbs on the scales of culture, and the selection of JD Vance seemed like a clear power grab, but the actual assumption of unconstitutional authority by Musk was unexpected, and has been a little bit of a shock. I don’t yet have a definite take on the Elon situation, beside that I think it’s deeply tied into what John Ganz has called “groyperfication.2” It’s very hard to say where any of this is going right now, and again, I don’t want to necessarily bother anybody with my political musings, but I will probably continue to do so.

The Representative man: Emerson on Plato

In his eighth book of the Republic, he throws a little mathematical dust in our eyes. I am sorry to see him, after such noble superiorities, permitting the lie to governors. Plato plays Providence a little with the baser sort, as people allow themselves with their dogs and cats.

I recently read the first part of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Representative Men, on Plato this week. I have received the impression, both in my formal education and during my autodidactic journey through philosophy, that Emerson is not taken especially seriously except by self-help fans and scholars of nineteenth century America, which seems like a pretty glaring mistake to me. There is probably an argument to be made that he’s a little derivative of the German Romantics, but he has certain (I am sorely tempted to say American) virtues that they lack. His lecture on Plato is fascinating and rich in its brevity, giving the master his due.

A key to the method and completeness of Plato is his twice bisected line. After he has illustrated the relation between the absolute good and true, and the forms of the intelligible world, he says: —"Let there be a line cut in two unequal parts. Cut again each of these two parts, — one representing the visible, the other the intelligible world, —and these two new sections, representing the bright part and the dark part of these worlds, you will have, for one of the sections of the visible world, — images, that is, both shadows and reflections; for the other section, the objects of these images, —that is, plants, animals, and the works of art and nature. Then divide the intelligible world in like manner; the one section will be of opinions and hypotheses, and the other section, of truths." To these four sections, the four operations of the soul come-spond,— conjecture, faith, understanding, reason. As every pool reflects the image of the sun, so every thought and thing restores us an image and creature of the supreme Good. The universe is perforated by a million channels for his activity.

All things mount and mount.

Emerson makes a fascinating critique of Plato’s form, that least philosophic style which nonetheless makes him one of the few philosophers who are a joy to read, who can be productively read without possessing the pedantic and somewhat antiquarian mind of a scholar.

It remains to say, that the defect of Plato in power is only that which results inevitably from his quality. He is intello-tual in his aim; and, therefore, in expression, literary. Mount ing into heaven, diving into the pit, expounding the laws of the state, the passion of love, the remorse of crime, the hope of the parting soul, — he is literary, and never otherwise. It is almost the sole deduction from the merit of Plato, that his writings have not, — what is, no doubt, incident to this regnancy of intellect in his work, — the vital authority which the screams of prophets and the sermons of unlettered Arabs and Jews possess. There is an interval; and to cohesion, contact is necessary.

It’s always fascinating to read one great mind on another, and I look forward to assimilating the remainder of Representative Men in the coming weeks. If I find something especially notable I’ll be sure to let you all know.

While I’m on the topic, since he invaded my last post, there’s something that feels very symbolic about the fact that Harry Jaffa died just over five months before Trump rode that golden escalator and announced his candidacy.

I’ll say off the cuff that this trend reminds me somewhat of the “don’t read theory” phenomenon of the online left of the 2010s, when viral tweets about landlords and aphorisms delivered by Brooklynite cocaine addicts on a podcast episode in 2017 were treated as being of greater value and relevance to the present situation than foundational works of theory and the input of genuine intellectuals. Obviously the groyper phenomenon is much, much dumber, but the mechanics of the thing seem basically similar to me.

>I have received the impression, both in my formal education and during my autodidactic journey through philosophy, that Emerson is not taken especially seriously except by self-help fans and scholars of nineteenth century America, which seems like a pretty glaring mistake to me. There is probably an argument to be made that he’s a little derivative of the German Romantics, but he has certain (I am sorely tempted to say American) virtues that they lack.

I went into this at one point and came to the straightforward conclusion that his seriousness was one of the general casualties of the self-immolation of the American WASPs (along with many others like William James, A. N. Whitehead, and Carl Jung). Emerson was extremely influential on Nietzsche, not subtly (though Nietzsche rarely names those he most admired outside of his journals), and he definitely deserves more attention, but the current elect of the academies have trouble with engaging, understanding, and digesting older-style sincerity... for powerful political reasons that a close reader of Strauss won't be ignorant of. Iirc Nietzsche agreed explicitly that those American virtues of Emerson's were important additions and complements to Romanticism.