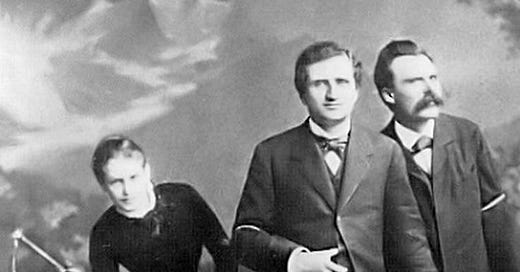

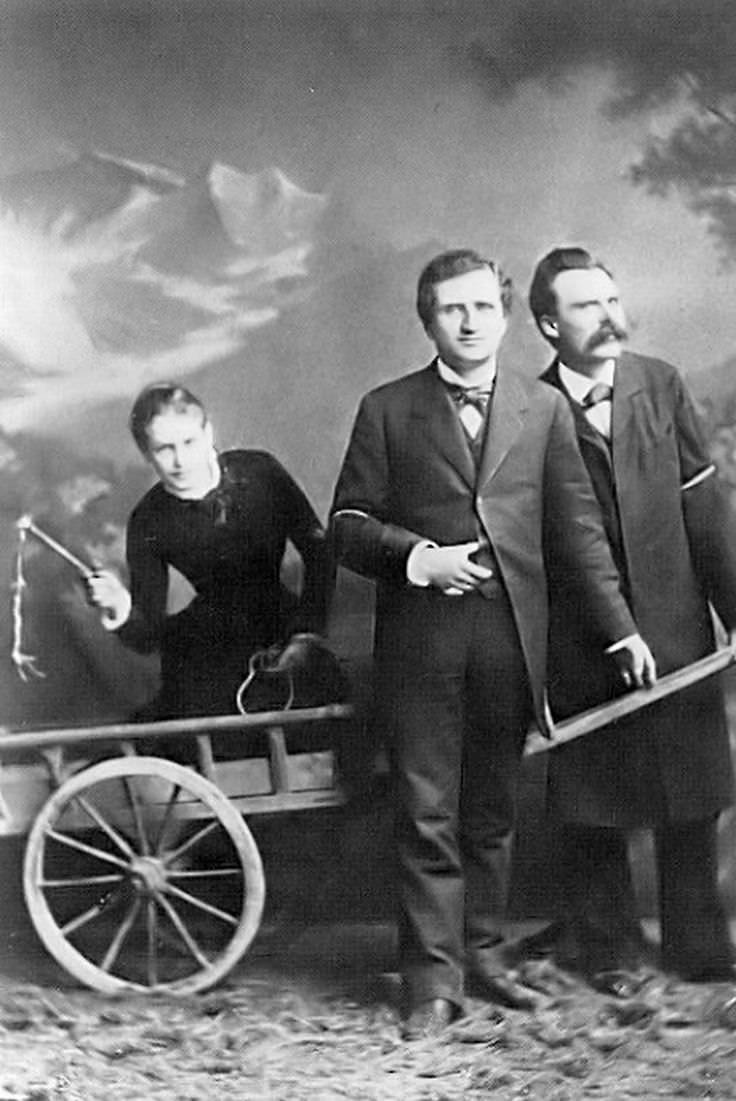

Friedrich Nietzsche is in many ways the philosopher of our age, somewhat remarkably given that he died more than 120 years ago. He was the great innovator of what Leo Strauss (more on him later) described as the “third wave” of philosophic modernity

The third wave may be described as being constituted by a new understanding of the sentiment of existence: that sentiment is the experience of terror and anguish rather than of harmony and peace, and it is the sentiment of historic existence as necessarily tragic; the human problem is indeed insoluble as a social problem, as Rousseau had said, but there is no escape from the human to nature; there is no possibility of genuine happiness1

He influentially perceived many of the grievances and frustratons that would characterize our time. We live in a profoudly Nietzschean moment. A subscriber asked me recently what I characterized as the signs of the new romanticism, and I realized that a lot of what I'm thinking of when I think about those tendancies is connectable to N. though he did disavow the movement as decadence after his early writings, something of the odor of romanticism does cling to his work.

The enigmatic point from my perspective is the question of how much Nietzsche actually has access to the deep truth of modernity. In certain ways I am very much with him, in certain ways I an very much against him as an Atonist-Christian-Platonist or whatever. There is a strand of my thinking that agrees with the 20th century left-liberal domestication of N.'s thought wherein his imperative to become what one is metamorphosed from the message of the übermensch to something Denise who works in accounting is capable of metabolizing and deriving profit from. On the other I do think that we should accept limits, and I worry that you maybe can't separate the side of Nietzsche embodied by contemporary culture on the left and center from the parts of him embraced by the right, where he sounds a little like a fascist. I still have to make it through The Will to Power and a few early works, but honestly I might take a break after that!

I've been rereading Ecce Homo, which I read as an undergrad, actually at the very end of my formal education. I remember walking away from the course thinking Kierkegaard was a bit more to my liking, a bit less unpleasant. I've written before that I've always gotten the impression that N. never really freed himself from ressentiment, that he his writings are on some level infected by that which he opposed, and I do largely still think that, though I am open to alternate readings. Laurence Lampert argues toward the end of the other book I’ll be taking a look at today that N. simply didn’t live long enough (in anything like sanity) to finish the Yes-saying work which would have provided context and for which the crazed late works were mere advertisements.

I was fascinated on the second time around by this passage, which seemed to anticipate the whole post-Paglian secular essentialist complementarian criticism of feminism. It has a very different feel coming from a German man who died in 1904, but I promise if you look around Substack or UnHerd you can find at least two dozen young women my age to five years older who sound exactly like this while making their criticisms of choice feminism, neoliberal girlbossery and the like.

"Emancipation of women" -that is the instinctive hatred of the abortive? woman, who is incapable of giving birth, against the woman who is turned out well &—the fight against the "man" is always a mere means, pretext, tactic. By raising themselves higher, as "woman in herself," as the "higher woman," as a female "ideal-ist," they want to lower the level of the general rank of woman; and there is no surer means for that than higher education, slacks, and political voting-cattle rights. At bottom, the emancipated are anarchists in the world of the "eternally feminine," the underprivileged whose most fundamental instinct is revenge.2

Lark’s tongues on the backstreets of layplaying

As I was driving to my mother's house in Vermont the other day I was listening to a few old favorites and some albums of more recent acquaintance. King Crimson's 1973 LP Lark's Tongues in Aspic is rightfully regarded as both one of their greatest and one of the contenders for its parent decade. Robert Fripp described their 1969 debut album as Bartok meets Jimi Hendrix, while someone whose reviews I used to follow described this one as Stravinsky meets Hendrix. Out-there stuff, sometimes violent, sometimes soft. I recommend it highly. The early/mid 70s were pretty heavily divided between"artsy" and "rootsy" as far as popular music went, and while in the long run culturally if not actually aesthetically the roots won out (as so often happens with these things a synthesis of the two predominated) during the 1980s. I also listened to Bruce Springsteen's 1975 clasic Born to Run. I've never been a huge fan of the Boss, he's always been someone who influenced a lot of artists I like without ever really himself being much to my liking. Eventually I did realize that I couldn't in good conscience like tom waits as much as I do without at least giving Springsteen a chance. Honestly he might be a perfect example of an artist who embodies what I was mentioning just now with the glam-roots quality of his eighties work. I like the title track to Born to Run now, although I hated it when I was 14, and 22-year old me loved that there’s a Prefab Sprout song gently mocking it.

I haven't gotten very far into the book yet but i've started reading Didion’s Play it as it Lays and will be rereading Run, River and the book she wrote in the nineties more or less autocancelling it, in the nakedly cynical hopes of capitalizing on the release of her journals (which I have no intention of reading and honestly wish they weren’t releasing) in April. I may write about that more next time!

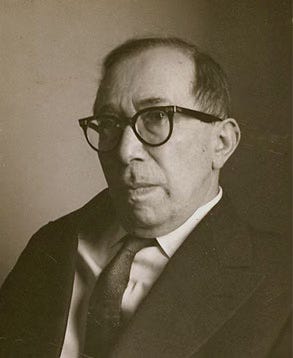

Theological-political problems: Strauss & Nietzsche

I've spent much of the last week slowly reading the late Laurence Lampert's 1996 Leo Strauss and Nietzsche, a book length commentary on Strauss's enigmatic late essay "Note on the Plan of Nietzsche's Beyond Good and Evil." I would describe this as amongst the best symathetic but skeptical accounts of Strauss's philosophical activity, probably the beat I've read with Stanley Rosen's Hermeneutics as Politics, and in certain ways offering a similar analysis. Both Rosen and Lampert fault in Strauss a certain evasions of the deep questions of modern philosophy posed by thinkers such as Nietzsche, although from very different perspectives-Lampert is a Nietzschean and Rosen a more traditionally modern if eccentric philosopher.

The most severe criticism of Strauss from a Nietzschean perspective must be that he understood the Nietzschean moment in our history but failed to flaunt it, to become its reasoned advocate. Nietzsche claimed the Persian virtue, "to speak the truth and shoot well with arrows" (EH Destiny 3), the virtue of "the strongest most evil spirits" who have so far done the most to advance humanity (GS 4), the virtue most essential if the present is to be a moment of advance beyond the merely modern. Strauss's virtue cast his lot with "those who cultivate the old thoughts, the farmers of the spirit" (GS 4), Ischomachus and his like, blind masters praying for grace while presuming to teach lessons to nature. By writing as he did, Strauss endorsed a premodern Platonic politics that encouraged obfuscation, gave heart to the irrational, and was not ashamed of intellectual uncleanliness. An odd com-bination, this late in the day, of Epicurean and Platonist, Strauss dwelt within a carefully walled garden cultivating an observer's naturalistic understanding of the whole while encouraging a public Platonism outside the garden wall as the only possible preservation of both the public and the garden. Perhaps Strauss saw still less reason than did Nietzsche for any hope and therefore prepared as he thought best for the coming night, the eventual collapse of philosophical inquiry in the modern world.

Strauss's great legacy, it seems to me, is compromised by his lack of boldness on behalf of philosophy at a decisive moment in its history. No one could reasonably accuse Strauss of cowardice, given what he was willing to bear on behalf of his undertaking for philosophy. Nevertheless, to have come so near to Nietzsche, to have penetrated Plato to his radical core, to have seen the history of genuine philosophy in all its breathtaking ambition, to have understood so clearly the inward intransigence of philosophy's opposition to the idiocies of revealed religion —and then to have whispered the results of these intrepid voyages of the mind in a way that makes them accessible only to such a small number of readers blinded neither by contemporary intellectual fashion nor by excessive loyalty to the piety of his own texts—that, it seems to me, is a failure of the historical sense..3

Leo Strauss and Nietzsche is a fascinating book, well-argued and learned, if partisan in the sense that Lampert certainly had his preference between the two. He is to be sure sympathetic to Strauss, but he views him nonetheless with a certain undiguisable disappointment, as someone who grasped Nietzsche's truths as few readers have, and yet rejected them in favor of a dying God and a dying philosophy, the Farabized political Platonism which makes up Strauss's teaching. The maneuver Strauss made and his students carried on, of propping up

The strategic conflict between Strauss and Nietzsche can be put this way:

Why force philosophy to make concessions to a moral world view at the very moment in which that world view is becoming publicy discredited? Did Strauss take this event seriously enough? Nietzsche himself continued and advanced the spiritual warfare, both ancient and modern, that was partially responsible for the greatest recent event: "Hooray for physics!" Nietzsche says (GS 335). Physics-open inquiry into the natural order and public display of the results—assists in the triumph over the historic moralism with which Platonism made its compromises. Did Strauss take modern science seriously enough as a public presence contributing to the greatest recent event?4

On his own terms Lampert makes a very strong case for Strauss as a transformative minor figure-not someone who creates values as a Plato or a Nietzsche, but rather as a gifted early receiver of a world-shaking teaching. I am not a Nietzschean (any more than any of us are as late moderns), and I am significantly more sympathetic to (this reading of) Strauss’s politics than Lampert, but this interpretation seems basically right to me. He wisely separates the teaching of the Straussians from their teacher-I don’t entirely share the dismissal of Allan Bloom and co, but largely agree that whatever they might have thought they mostly wound up doing (a group of) different thing(s) from Strauss. I understand that Lampert wrote several other books on Strauss before his death last year, and I will be certain to look into them on my ongoing journey.

Lampert, Laurence. Leo Strauss and Nietzsche. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. Basic Works of Nietzsche, translated by Walter Kauffman. New York, New York: Modern Library, 2000.

Strauss, Leo. “The Three Waves of Modernity.” Essay. In An Introduction to Political Philosophy: Ten Essays by Leo Strauss, edited by Hilail Gildin, 94–95. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press, 1989.

Leo Strauss, “The Three Waves of Modernity,” essay, in An Introduction to Political Philosophy: Ten Essays by Leo Strauss, ed. Hilail Gildin (Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press, 1989), 94–95.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Basic Works of Nietzsche, trans. Walter Kauffman (New York, New York: Modern Library, 2000), 723.

Laurence Lampert, Leo Strauss and Nietzsche (Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 184.

Ibid,

This was great to read, thank you!

Your writing on Nietzsche reminds me of how, in Andrew Wilson’s biography of Sylvia Plath, Mad Girl’s Love Song, he all but places Plath’s “turn into madness,” or whatever at Nietzsche’s feet because he is taken aback by how much Plath becomes beholden to Thus Spake Zarathustra. Reading that Plath bio, I was struck by how Wilson treats Nietzsche as a danger to women prone to big egos, writerly talent, and flights of backwards mora fancy or whatever, Plath being someone he kind of looks down for having all three.

Your comment about our “profoundly Nietzchean” moment is cause for explicit celebration in the work of religious studies scholar Jeffrey Kripal, whose 2022 book The Superhumanities argues that we can save the humanities, in part, by triumphantly reclaiming the human experience of altered and paranormal states of consciousness. He explicitly ties these states to Nietzche’s ubermensch. It’s a fascinating if wildly uneven read (I get the sense Kripal’s earlier work is better; practitioners on the occult scene are quite taken with him and with Nietzche, maybe for obvious reasons!)

Your struggles with Nietzsche make me think you'd get a lot of mileage out of Daniel Tutt's *How to Read Like a Parasite*. Really you should be reading Losurdo's *The Aristocratic Rebel* and Rehmann's *Deconstructing Postmodern Nietzscheanism*, but Tutt's little volume is definitely the easier task there.