As I’m sure you’ve noticed, I’m glacially slow at producing essays, and despite having a few in the tank (a long-gestating piece on Albert Murray and an entry into the canon of recent poptimism discourse) I find myself once again throwing together another digest of what I’ve been reading and thinking about in the last (few) month(s) or so.

Shame Beyond Socrates: Strauss, Kojève and Rosen

I’m still on my Straussian kick.1 The more I read the less I know what to make of him. There are multiple possible teachings here-charming but eccentric conservative continental philosopher concerned primarily with avoiding relativism, reactionary thinker who probably does have more in common with Heidegger and Carl Schmidt than many of his defenders would like to admit- and yet he also seems at times to mount something like a grudging defense of western liberalism as a place where philosophy can be preserved. There’s also the whole “engineering the best society by psyopping its elites” thing, which I’m not 100% is present in the writings of the man himself, but certainly seems to be in effect to some extent within the Straussian tradition post-Strauss.2 I have a little sympathy for an aesthetic version of this-deep down I do maybe agree with Allan Bloom that the pursuit of philosophy and the appreciation of art are about an ascent from inherited prejudices-but I’m not so sure about it as politics.3 Strauss definitely feels like (one of the) patient zero(s) for the idea that feels more and more and more common these days that yes, religion and all conventional narrative are bunk-he certainly seems to imply this, especially in Persecution and the Art of Writing- and yet only the natural aristoi, the intellectuals of the highest order should be able to play with identities, reject convention, question metaphysics and public morals and so on, while all the rest need edifying lies, need to obey the Law, or else (as in the modern variation) get handed a watered down version of it from evopsych guys or neo-jungians. The more I read the less certain I am that I understand. Straussian pedagogy is somewhat notoriously discussed as seductive, but the texts are seducers in their own regard. I’ll let you know if I ever figure out the secret.

There are a handful of texts from the last century one wants to press into the hands of every thinking person with the charge this explains the world, and Alexandre Kojève’s Introduction to the Reading of Hegel: Lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit is one such book. I refer not so much to Kojève’s radical revision of Hegel via Marx and Heidegger-I can dig what he’s doing, more or less what Plotinus does to Plato or Aquinas or Averroes do to Aristotle, but it’s not Hegel -as to the lengthy afterlife it’s enjoyed amongst thinkers on both sides of the Atlantic. I can’t believe that I read Sartre without having ever touched this book.

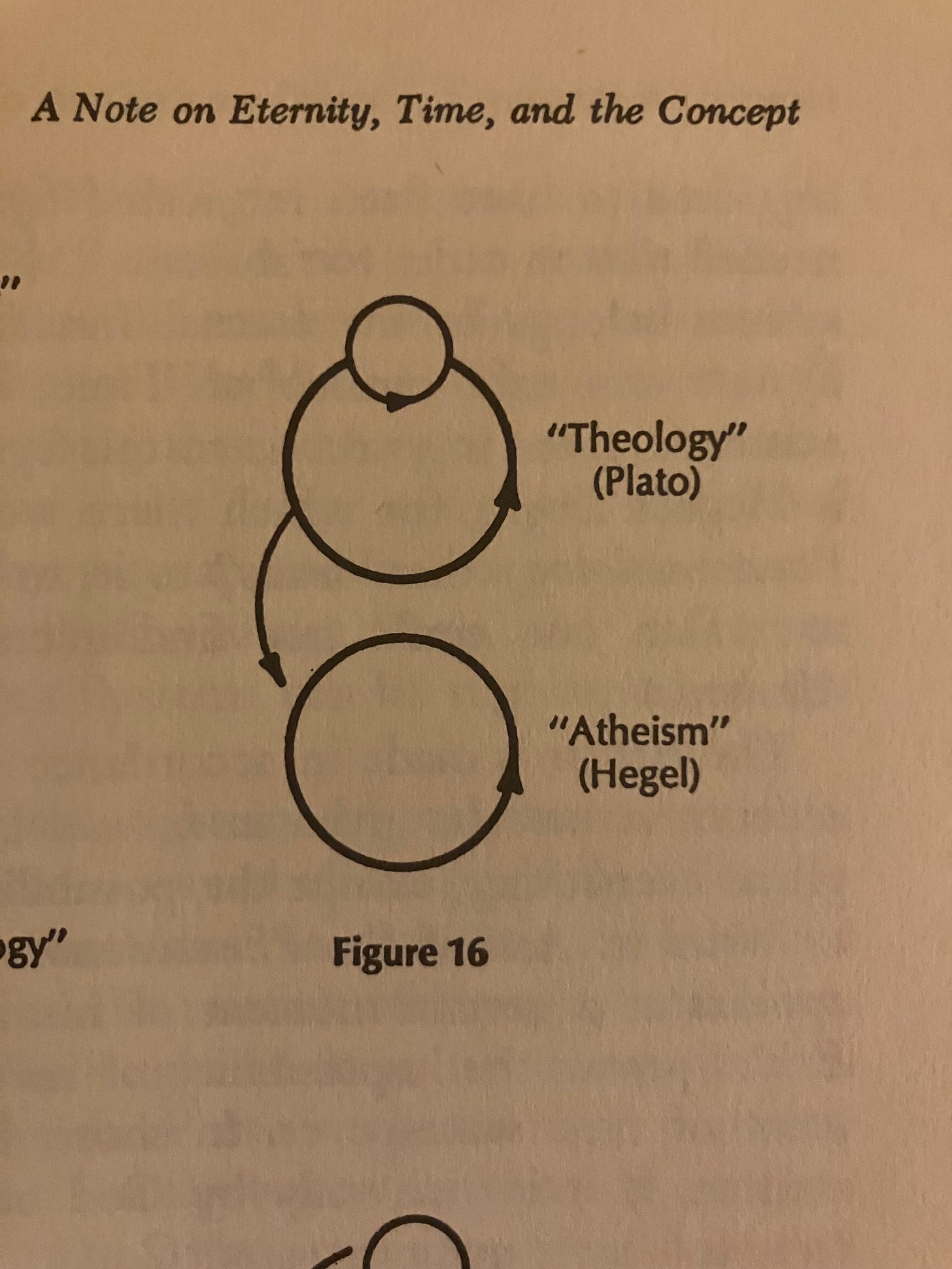

Normally I find the diagrams in francophone philosophy tiresome and question their necessity, but here I actually found them invaluable- the description of Hegel's system as a perfect circle contrasted with the incomplete or supplemented circles of other philosophers did more for me than all the descriptions I’ve ever read.4 It’s interesting that this was so influential on existentialism-Kojève says that we must be atheists, that we must face the inevitability of our own annihilation in order to attain self consciousness and wisdom, but surely we also must face the possibility of not-knowing?

Speaking of which, I’ve been enjoying Stanley Rosen’s Hermeneutics as Politics, which was recommended by a reader last month. I’m not quite done, but I’m really enjoying the section on Strauss and Kojève. As a supplement I’ll add something Rosen said about Kojève toward the end of his own life:

I have come to the conclusion that my initial intuition, formed during the year of my study and weekly contact with him, was correct: Kojève’s system was unworthy of his intelligence and even of his illuminating commentaries on the Phenomenology. Not only this, but I believe that he knew its unworthiness, or at least suspected it, or knew it once but had allowed himself to forget it in the pleasures of his own success.

In short, Kojève presents us with the strange spectacle of a philosophical spirit of unusually high capacities who is spending his time in amusing himself as the only alternative to the impossibility of genuine philosophy. I want to say immediately that, with all of its posturing, Kojève’s play was much more illuminating than the serious work of almost all professional philosophers I have had the opportunity to know personally. I repeat: Kojève was a genius, not a charlatan. But he was a defective genius. He was too self-conscious, in the good and the bad senses of that expression, to lose himself genuinely in a system, and (to repeat), not self-conscious enough to exist without a system.

-Stanley Rosen, Kojève’s Paris

Lit Digest: Theory of the Novel, John Barth

This month I read György Lukács book length essay The Theory of the Novel. It’s quite something-a systemic, philosophical account of the novel in terms the older Lukács would denounce as “romantic anti capitalism”

I’ll admit I have my own Against Interpretation side, a part of me that has always rolled its eyes at any attempt to create a geometric system of aesthetics, a sphere of the fixed stars on which to hang some unifying theory, as if every color and every word could only be justified by our constructions, and this kind of essay has always tripped that particular element. With Lukács one can at least see in his subsequent career why he’s doing this. Following this book he became a marxist and eventually one of the premiere apologists for Stalinism, and it’s pretty apparent to me that he was looking for something near-religious in the novel.5

The novel is the epic of a world that has been abandoned by God. The novel hero's psychology is demonic; the objectivity of the novel is the mature man's knowledge that meaning can never quite penetrate reality, but that, without meaning, reality would disintegrate into the nothingness of inessentiality. These are merely different ways of saying the same thing. They define the productive limits of the possibilities of the novel-limits which are drawn from within-and, at the same time, they define the historico-philosophical moment at which great novels become possible, at which they grow into a symbol of the essential thing that needs to be said. The mental attitude of the novel is virile maturity, and the characteristic structure of its matter is dis-creteness, the separation between interiority and adventure.

As far as essay-length explications of literature from the 20th century I’d probably prefer Albert Murray’s The Hero and the Blues, which gives you a vision of actually living, actually trying to be heroic in the ruins, as opposed to the posture in which Lukacs leaves us at the end and the retroactive beginning of his text, where literature is inadequate and you really do need some faith or creed to knock you down and turn out the lights on the road to Damascus. It’s a great read though!

I was saddened at the beginning of last month to note that John Barth had passed away.6 His reputation had fallen pretty sharply in the last few decades-I suspect for several reasons*- but his best works are amongst the more interesting American fiction of the late 20th century. On a sentence-to-sentence level he lacked the genius some of his peers, but he was a craftsman and an experimenter, and I certainly do recommend him to you. The first three novels form a sort of loose existential trilogy culminating in the mammoth Sot-Weed Factor, among other things a surprisingly thoughtful musing on postmodern manhood refracted through a bawdy colonial sendup of the 18th century novel, and those are probably the books I’d send you to read first. There’s good work throughout his career, but there’s something about those first three that was never quite recaptured. I may write something in greater depth later on.

I seem to have once again (half-converted myself to the system of a thinker I was interested for other reasons. I’m certainly not entirely persuaded, but I find myself quoting Strauss in casual conversation, jokingly describing myself as a Straussian, etc. This lasted until I reminded myself how little of a place there is for someone like myself in the various existing Straussian systems.

Shadia Drury argues in The Political Ideas of Leo Strauss that the distinction between philosophically-oriented “East coast Straussians” and politically focused “West coast Straussians” that developed between Allan Bloom and Harry Jaffa was a deliberate move by Strauss, and that Jaffa and his followers at Claremont represent the political cadre of a machiavellian scheme of social influence-an “outer circle” of minimally philosophic gentlemen aiming to influence the United States in the good Professor’s preferred direction. This is (imo) the least convincing of the critiques offered by her book.

To give away one of the parts of an upcoming essay, there’s something of the metaphor of the cave-below-the-cave in Persecution and the Art of Writing or what Bloom says about prejudice in Closing to my thoughts about poptimism.

I’m pretty sure I’m more of a Kantian based on Kojève’s description and depiction of the various systems. Surely we can’t ever actually close the circle? (This may be incorrect, I have not read vast amounts of Kant)

I recently put his mammoth history/denunciation of post-Hegelian German thought The Destruction of Reason on my to-read list, due in part to the similarity to the aim of Natural Right & History and other writing of that period.

Somewhat fittingly he outlived the writer of his own obituary in the Times by nearly 14 years.

A book I always recommend to those getting into Strauss is Robert Howse's Leo Strauss: Man of Peace. Howse is the (exceedingly) rare Strauss aficionado who comes from the Bernie Sanders left. While his book over-liberalizes Strauss, in my view, it remains a superb corrective and insightful intellectual history. Howse is particularly good--indeed, irreplaceable--in the distinction he draws between Strauss and Schmitt, and, hence, between the philosophic and the warlike lives.

Just noticed your note on The Destruction of Reason, it isn't GL at its best but you are spot-on about its similarity to Natural Right and History. The Marxist historian Gopal Balakrishnan (now rightly disgraced for sexual harassment but that's another story) used to say that you could substitute passages from one book to the other without the reader noticing.