Hi! The following is a very belated attempt to think through some themes which were going around in the notes about a month ago. It doesn’t quite cover the full promised response, and so will likely have at least one followup post. enjoy!

The time comes when each one of us has to give up as illusions the expectations which, in his youth, he pinned upon his fellow-men, and when he may learn how much difficulty and pain has been added to his life by their ill-will.

Sigmund Freud trans. James Strachey, Civilization & Its Discontents

My fascination with psychoanalysis has mostly been in remission for the last while, but real ones will recognize it as one of the major running threads of this blog. I might be more likely to cite from Natural Right & History, The Argument of the Action, or The City & Man these days, but that doesn’t change the fact that those blue and gold volumes of the Standard Edition are resting on my bookshelves, or that I’ve more than once perused the Ecrits (largely uncomprehendingly.) When I first read Freud, longer ago then I can remember-although not in the years where I walked past a statue of him nearly every day-I was much less versed in 19th century Germanophone philosophy than I am now. It seems remarkably clear for instance how much he borrowed from Schopenhauer, whose pessimistic attitude to much of life Freud shares in many respects. One way to conceptualize Freud as a thinker might be as a very late, perhaps the last, representative of what Leo Strauss called the “first wave” of modernity. Due to this belatedness his picture of human possibility is heavily qualified and influenced by that of the third wave, which Strauss describes thus:

The third wave may be described as being constituted by a new understanding of the sentiment of existence: that sentiment is the experience of terror and anguish rather than of harmony and peace, and it is the sentiment of historic existence as necessarily tragic: the human problem is indeed insoluble as a social problem, as Rousseau had said, but there is no escape from the human to nature: there is no possibility of genuine happiness, or the highest of which man is capable has nothing to do with happiness.

Freud is certainly less optimistic than the great thinkers of the first wave such as Spinoza and Locke, more alive to the darkness within the human spirit in the manner of the later thinkers of the third. Nonetheless, he persists in esteeming a high place for reason’s clarifying and illuminating faculty, and for that reason he is probably as Peter Gay argued, a figure of the enlightenment. While the late Freud of the drives may have possessed a darker and more nuanced vision of the human, he seems to have believed on some level down to the end that the cobwebs and medieval statuary of the mind could be cleared away & the place redecorated in modern style. This week I finished reading Freud’s 192 Civilization and Its Discontents, his great treatise on human aggression and darkness.

When we justly find fault with the present state of our civilization for so inadequately fulfilling our demands for a plan of life that shall make us happy, and for allowing the existence of so much suffering which could probably be avoided-when, with unsparing criticism, we try to uncover the roots of its imperfection, we are undoubtedly exercising a proper right and are not showing ourselves enemies of civilization. We may expect gradually to carry through such alterations in our civilization as will better satisfy our needs and will escape our criticisms. But perhaps we may also familiarize ourselves with the idea that there are difficulties attaching to the nature of civilization which will not yield to any attempt at reform.

This is the Freud one discovers as a reader of mid 20th century cultural and poltical writing, an Augustinian figure who reintroduces original sin for a world which found itself no longer able to believe in God. The early works of Philip Rieff (cowritten with Sontag or solo) for which he is best remembered are all essentially footnotes to this book, as is much of the work of Erich Fromm and some of the best remembered writings of Herbert Marcuse. To quote from the opening sentence of Eros and Civilization:

The concept of man that emerges from Freudian theory is the most irrefutable indictment of Western civilization—and at the same time the most unshakable defense of this civilization. According to Freud, the history of man is the history of his repression. Culture constrains not only his societal but also his biological existence, not only parts of the human being but his instinctual structure itself. However, suchcconstraint is the very precondition of progress. Left free to pursue their natural objectives, the basic instincts of man would be incompatIble with all lasting association and preservation: they would destroy even where they unite. The uncontrolled Eros is just as fatal as his deadly counterpart, the death instinct. Their destructive force derives from the fact that they strive for a gratification which culture cannot grant: gratification as such and as an end in itself, at any moment. The instincts must therefore be deflected from their goal, inhibited in their aim. Civilization begins when the primary objective—namely, integral satisfaction of needs—is effectively renounced.

There are several layers to my interest in psychoanalysis, from one of my favorite teachers in middle school explaining Freudianism to the class (as well as one could be expected to do so for a bunch of 7th graders,) or the fact that I walked past a statue of him every day for four or so years as an undergrad. If asked however, I would point to the phenomenon of leftist bloggers in the aughts and 2010s who wanted to be Mark Fisher or Slavoj Žižek and were thus steeped to the gills in psychoanalytic lore, especially of the Lacanian variety. I am somehow tempted to say that I got more from them than my formal education, which isn’t true at all—the sense of 19th and 20th century American and global history I received in collect still basically underpins my understanding of current events— but in terms of theory and philosophy, most of what I got in those years I got from millennial bloggers trying to explain dialectical materialism through Doctor Who and Alan Moore or the like. This sort of thing, and the grown-up counterparts thereof in magazineworld and elsewhere, is partly what I believe

was talking about when he recently wrote of “2015-2021, which to me was a golden age of left-wing thought and public intellectualism in general, with an extraordinarily high level of public writing and debate” in response to and ’s colloquium on antiwokeness. I have mixed feelings on this sentiment.Certainly there is a stronger vernacular current on the left than there was thirty years ago, or even for that matter in 2010. Ideas that were controversial and the reserve of academics burning the home fires in solitary despair when I was a child are now on the lips and the touchscreens of the masses. Still, it seems that in one respect the situation has not fundamentally changed. In 2025, there appears to be no revolutionary subject in the United States, or seemingly elsewhere in the west. The currents brought to light by the crash of the global economy in 2008 and the decade+ of austerity and difficult recovery which followed it, and which were manifested in Bernie Sander’s two primary runs and Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party are still with us, but the dreams of tangible political action based upon them seem for the moment conclusively dead & buried. Thirty-six years after the essay and thirty-three years after he published the book, Francis Fukuyama, while mocked and himself somewhat changed in position, has not yet been disproven. The gate may seem to inch a little closer to opening every day, but history for the moment, however uneasily, remains over.

For nearly a year now

(to whom this post is largely a response) has been trying to get me to read New Left Review guru Perry Anderson's essay on Fukuyama’s famous thesis, "The Ends of History" collected in his 1992 book A Zone of Engagement.1 Having now done so I see why he was so adamant, and furthermore why it's so crucial to our Hegelian rodent friend's project. "The Ends of History" is one of those essays one wants to press into the hands off every thinking person one knows, a work which seems to explain some quality of the world we live in today that had hitherto eluded. In just under 100 pages Anderson chronicles the history of the idea of the end of history itself, from Hegel down through the nineteenth century to Alexandre Kojève's famous formulation in his lectures in prewar Paris, down through to Francis Fukuyama's essay and then book. (In the process Anderson both puts some respect on Leo Strauss’s name and relegates him to the place he probably belongs in if one subscribes to the currents to which Anderson does.) It’s an essay which makes one think about where they stand in these matters. In general, I might describe my own position as "left-agnostic" more or less. I’ve been antagonistic to it, I’ve been a fellow traveller, Ive been antagonistic to it again, & now I suppose I should leave the door open, more or less. Certainly one sees what both the smarter and the less sophisticated thinkers mean: it certainly doesn't seem like our system is particularly sustainable, and I often find merit to the critique made in the 1992 piece that there are material and ecological constraints which prevent the levels of consumption enjoyed by the inhabitants of the western world at present (and although this was not yet a reality when the essay was new, increasingly China, as well) from being within reach of the majority of humanity. This agnosticism can be criticized- certainly one must wrestle with the implications of what Lukacs says about the western Marxists of the Frankfurt school in the famous 1962 preface to his 191 Theory of the Novel:A considerable part of the leading German intelligentsia, including Adorno, have taken up residence in the 'Grand Hotel Abyss' which I described in connection with my critique of Schopenhauer as “a beautiful hotel, equipped with every comfort, on the edge of an abyss, of nothingness, of absurdity. And the daily contemplation of the abyss between excellent meals or artistic entertainments, can only heighten the enjoyment of the subtle comforts offered.”

On the other hand, this case can be made if and only if one believes, as Lukács did, and continued to even after the system had abused and imprisoned him, that there is a viable course of action that these thinkers have merely chosen to ignore out of some moral or philosophical failure. I have no such belief, and as such despite my reservations basically continue to dwell in that grand hotel overlooking an abyss with a host of other more or less dissatisfied observers living or dead. Anderson in his younger days seemed to share Lukacs sense of a failure on the part of the western left, as described in his 1976 essay Considerations on Western Marxism. Here he makes a critique of the various thinkers not unlike that of Lukács, considering the tradition as a whole overly philosophical & concerned with superstructure over base. Anderson's more recent work, although I am not the expert which some are, seems to be more correct on this point. While still committed to the Marxist & leftist tradition, frankly more so than I have ever been, Anderson acknowledges here, & again in a recent NLR piece both that no alternative appears clear, and that it frankly may take a catastrophe or catastrophes to produce one.

An international regime being lowered into the ground, or rising anew like Lazarus? The stand-off in such expert verdicts has its correlate in the political landscape, where the conflict between neoliberalism and populism, the adversaries that have confronted each other across the West since the turn of the century, has become steadily more explosive, as events of the past weeks show – even if, for all its apparent compromises or setbacks, neoliberalism retains the upper hand. The first has survived only by continuing to reproduce what threatens to bring it down, while the second has grown in magnitude without advancing in meaningful strategy. The political deadlock between the two is not over: how long it will last is anyone’s guess.

Does that mean that until a coherent set of economic and political ideas, comparable to Keynesian or Hayekian paradigms of old, has taken shape as an alternative way of running contemporary societies, no serious change in the existing mode of production can be expected? Not necessarily. Outside the core zones of capitalism, at least two alterations of great moment occurred without any systematic doctrine imagining or proposing them in advance. One was the transformation of Brazil with the revolution that brought Getúlio Vargas to power in 1930, when the coffee exports on which its economy relied collapsed in the Slump and recovery was pragmatically stumbled on by import substitution, without the benefit of any advocacy in advance. The other, still more far-reaching, was the transformation after the death of Mao of the command economy in China in the Reform Era presided over by Deng Xiaoping, with the arrival of the household responsibility system in agriculture and the ignition by township and village enterprises of the most spectacular sustained burst of economic growth in recorded history – this too was improvised and experimental, without pre-existent theories of any kind. Are such cases too exotic to have any bearing on the heartland of advanced capitalism? What made them possible was the magnitude of the shock and depth of the crisis each society had suffered: the Slump in Brazil, the Cultural Revolution in China – tropical and oriental equivalents of the blows to occidental self-assurance in the Second World War. If disbelief that any alternative is possible were ever to lapse in the West, the probability is that something comparable will be the occasion of it.

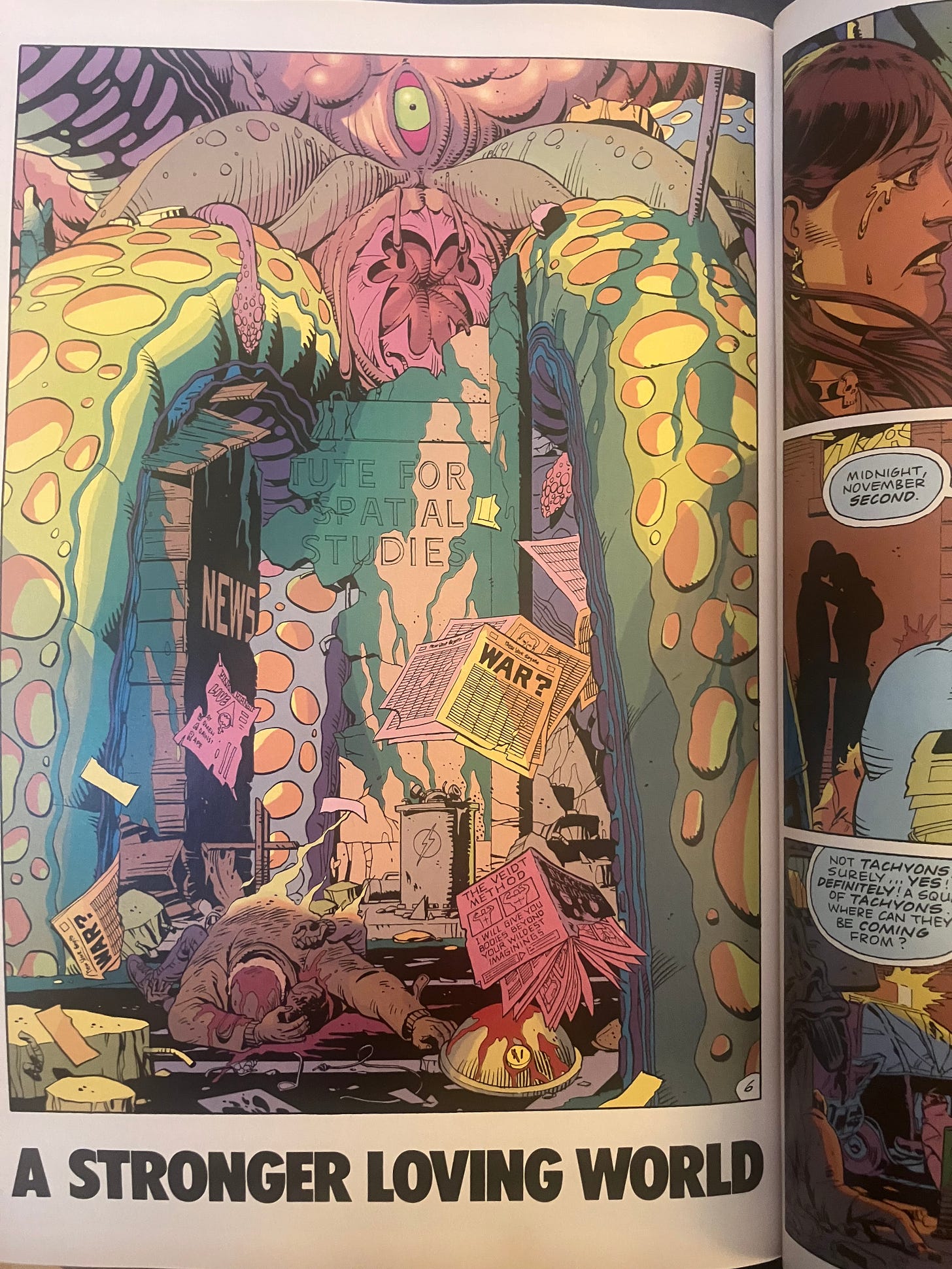

In college, (when I was as is so often the case the most sympathetic one is to the left) during one of those proverbial bull sessions walking from the seminar room to the dining hall I remember remarking to the most dedicated Marxist I have ever encountered in the physical world (I believe he was a Trotskyist) that I sometimes wondered—purely theoretically, even then I didn’t want anybody’s blood on my hands or mine on someone else’s—if there wasn’t something to the view, exemplified by the Maoists and especially the Cambodians in the twentieth century, that it would take something truly catastrophic for a revolutionary program to succeed.2 "Careful what you wish for" he said, perhaps taking me to be more earnest than I was. "Pol Pot didn't have much use for people like you.3” Some apprehension of this sort is still with me, but it has always seemed that to will, to seek to manifest some such calamity—even if, and this is an absolutely enormous 'if" —we do make it to a revolutionary society on the other end would be monstrous, something like Veidt's squid in Alan Moore's Watchmen.4 Kojève is supposed to have said that he left Russia during the revolution because he knew it would mean thirty terrible years, and he was ostensibly a Stalinist when he was delivering the lectures on Hegel for which he is best remembered.

Both Freud and Marx sit in strange places in the third decade of the twenty-first century. Neither man’s system has survived the last hundred years untarnished. There is something to the argument of sexism against Freud, or the assertion by Alvin Gouldner and others that Marxism under-theorizes the problem of what depending on whom you speak to is either the philosopher/the thinker/the officer class/etc. As a religious person and an observer of various forms of contemporary spirituality I think the confident 19th century materialism of both traditions is a weak point, and indeed often scans as rather legibly a product of a certain time, place, & social class. Still, these complexes of thought remain with us, and it seems likely that for the future we will continue to grapple with them. I’ll close with a direct quote from one of Secret squirrel’s replies to

, and a sentiment with which I am largely in agreement:What should have ended at the end of history moment was the illusion that we knew where history was going, that we were experiencing morbid symptoms that could lead either to a healthy birth or to the death of mother and baby, to socialism or to barbarism. (I think that this is one point where the “secular religion” criticism of Marxism has bite.) You can understand why Luxembourg, Lenin or Gramsci could talk this way, but we don’t really have the right to do so.

Works cited, mentioned in an earlier edit, etc:

Anderson, Perry. Considerations on Western Marxism. 3rd ed. London: Verso, 1976.

Anderson, Perry. “The Ends of History.” Essay. In A Zone of Engagement, 279–376. New York, NY: Verso, 1991.

Fisher, Mark. Capitalist realism: Is there no alternative? 2nd ed. London, UK: Zer0 Books, 2022.

Freud, Sigmund. The standard edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. (3), Civilization and its Discontents. Edited by James Strachey. New York, NY: W. W. Norton, 1989.

Fukuyama, Francis. The End of History and the Last Man. New York, NY: Free Press, 1992.

Hobsbawm, Eric. The Age of Extremes: The short Twentieth Century, 1914-1991. London, NY: Viking Penguin, 1994.

Lukács, György. The Destruction of Reason. Translated by Peter Palmer. London: Verso, 2021.

Lukács, Georg. The Theory of the Novel: A Historico-Philosophical Essay on the Forms of Great Epic Literature. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1974.

Marcuse, Herbert. Eros and civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1955.

Marcuse, Herbert. One Dimensional Man: Studies in the ideology of Advance Industrial Society. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1964.

Rieff, Philip. Freud: The Mind of the Moralist. 3rd ed. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1979.

Rieff, Philip. The Triumph of the Therapeutic: Uses of Faith after Freud ; with a new preface. Chicago, IL: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1993.

Strauss, Leo. “The Three Waves of Modernity.” Essay. In An Introduction to Political Philosophy: Ten Essays, edited by Hilail Gildin, 81–98. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press, 1989.

Last month I asked Secret Squirrel in his capacity as a NLR watcherfor his thoughts on a then-recent piece on said publication’s appreciation of the conservative Catholic NYT columnist Ross Douthat. I found the responses fascinating, and consequently was unable to adequately respond for around a month. This whole post is itself only covering half of what I set out to write.

When I was more of a fellow traveller the fallen socialist regime that most fascinated me was the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. This may just be the fascination with Mitteleuropa talking, but it seems like another fundamentally broken, probably doomed regime that nonetheless existed in a temporarily productive tension for a time. Furthermore-and this may just be the American subjectivity talking- I’ve always thought that if there had been a way to make 20th century state socialism work it would be something like workers self-management & market socialism .

On the other hand as one of our romantic-literary upstarts was recently suggesting on his super-secret tumblr, it probably is a problem for the left that so much oxygen has been and is expended on the defense of this or that current or fallen empire.

I am nearsighted and have worn glasses since I was 8 or so.

I have always had a certain unease with the left tendency to make this or that ethnoreligious nationalist movement abroad the representatives of global revolution. As Edmund Wilson wrote in the 1971 introduction for To the Finland Station“It is all too easy to idealize a social upheaval which takes place in some other country than one’s own.”

Personally, I don’t think searching for revolutionary will among the population tells you what is possible. It’s not there until it is. Such things are conjunctural, as are our feelings of optimism or pessimism. Capital remains the single most revolutionary force in human history, as the past few months have shown beyond doubt. Its immanent drives toward increasing concentration and continuous improvement in labor-saving technology have by no means been abated. Artificial intelligence is on schedule to decimate whole sectors of the labor force in the next five to ten years. We have no idea what that is going to do to American society and politics. Nor has capitalism overcome its inherent instability and recurrent crises of profitability. A recession is more likely than not in the near term. On an international level, the American empire, once an industrial powerhouse, has been hollowed out into a parasitic global protection racket and is entering a terminal decline. And imperialism has not outgrown its tendency to military conflict, as the escalating war-drive against China shows. In these conditions, revolutionary situations will arise. If not sooner, then a bit later. And if not in the West, then in the oppressed countries with a chance of extending to the imperialist heartland. The real question, I think, is not whether history is moving forward apace, but whether the workers movement and the left in its present weakened and disoriented condition will be up to the task of taking advantage of such chances as will surely come. Perhaps not—but in that case, it won’t be history’s fault but ours.

Fantastic stuff! I agree with Murdoch that the notion of original sin (whether of the Christian, Freudian or Darwinian variety) is not appreciated enough by the existentialists and their heirs. I mentioned Rieff (and your Lasch-Paglia intellectual dyad) in a forthcoming piece inspired by Matthew Gasda’s The Sleepers.