Hello, welcome back to the weekly digest! This week I have a sort of reminiscence about my spiritual history and “gnostic phase” and some thoughts on the Odyssey from Erich Auerbach and Seth Benardete. Enjoy!

Putting (or taking out) the Gnostic in Gnocchic:

2024 was the year I finally acquired a copy of and began reading Hans Jonas’ epochal study of Gnosticism, The Gnostic Religion: the message of the alien God. It should be said that it’s a somewhat outdated work as far as up to date scholarship goes-it was largely written before the Nag Hammadi discoveries of the 1940s came to light and were translated, and contemporary specialists often lean in the direction of discarding the term “gnostic” altogether, or at very least downplaying the notion of some kind of gnostic unity.

Accordingly we can speak of the Gnostic doctrine only as an abstraction. The leading Gnostics displayed pronounced intellectual individualism, and the mythological imagination of the whole movement was incessantly fertile. Non-conformism was almost a principle of the gnostic mind and was closely connected with the doctrine of the sovereign "spirit" as a source of direct knowledge and illumination. Already Irenaeus (Adv. Haer. I. 18. 1) observed that "Every day every one of them invents something new." The great system builders like Ptolemaeus, Basilides, Mani erected ingenious and elaborate speculative structures which are original creations of individual minds yet at the same time variations and developments of certain main themes shared by all: these together form what we may call the simpler "basic myth."

That being said, Jonas was an important thinker in his own right, part of a small group of students of Martin Heidegger who exerted an outsize if not always visible influence on late 20th century intellectual history. I’ll fill you in on more of the details when I’m finished with the book.

A few weeks back I left a comment on a

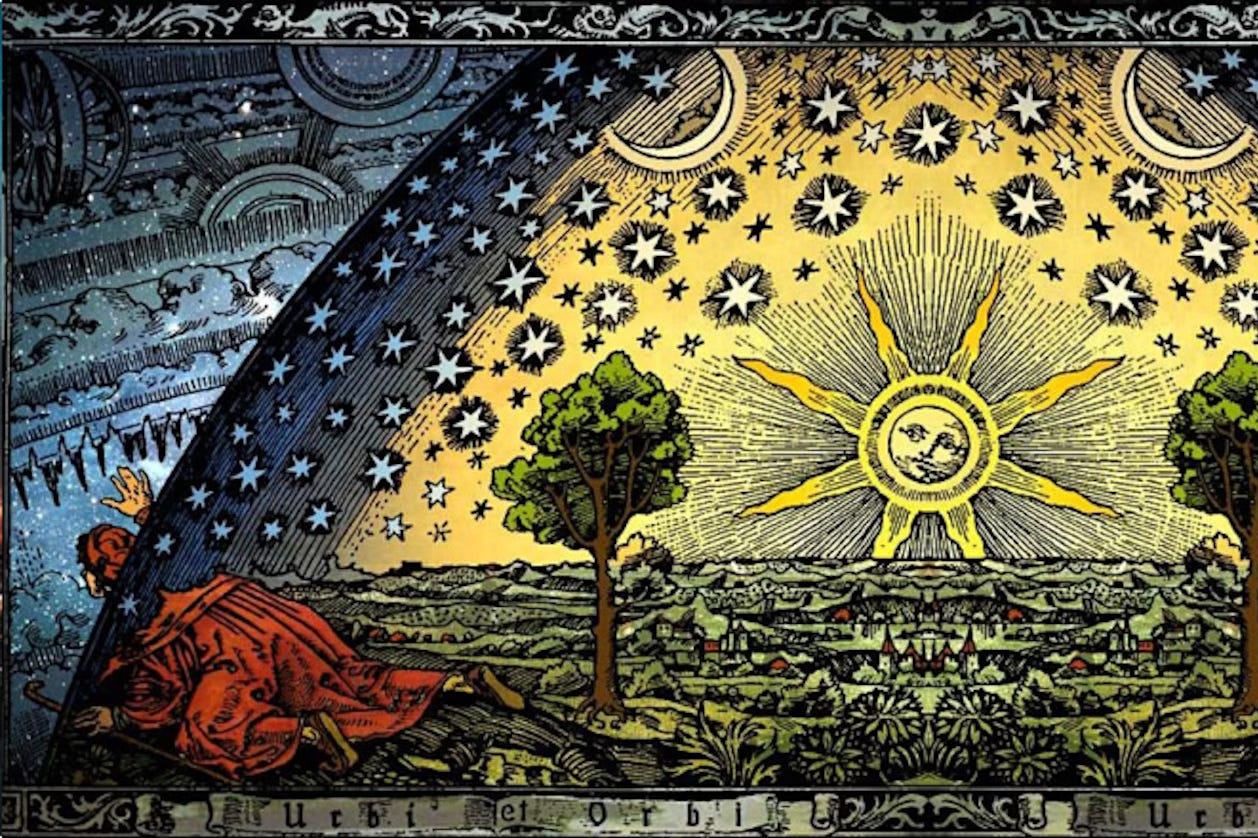

post copping to a "fairly serious ghostic phase" at an earlier point in my life. helpfully quoted this recently, and so while I remain as then mildly embarrassed by the whole affair, I thought I'd write about it a little this week. As background I should say that I was raised culturally if not always exactly spiritually protestant, th with the sort of very minimal but nonetheless real relationship to Christianity that was once much more typical, and which one sees traces of across late twentieth century american arts. During my teens I had a kind of spiritual awakening and got very very into the bible and to a much lesser extent church in a kind of very individualist, Idiosyncratic way that was very fragile but also very real. At that time I gravitated toward a more reformed outlook, but it's possible this had to do with the denomenation I belonged to growing up being descended from that tradition. My politice and theology were a mess when I was a teen.1In college as is often the case I had an existential crisis in my sophomore year in which I halfway persuaded myself that I was an atheist. The impermanence and the non-teleological nature of our modern episteme was weighing down on me, crushing me. Probably this was in some sense not about faith at all, but some recognition of my essential finitude and a feeling that I was not where I needed to be. There are many, I am told who find atheism or something like atheism liberatory. This has never been my experience. The moments when I have found myself closest to atheism have ben my my most anxious, blighted always by a crippling fear of death, o If one no longer believes in the storybook God of one's upbringing, if one no longer believes one in living in the kind of world that would be created by such a deity but is also unable to banish either the image of the Father smiting in cold command or the Son on the cross and breaking bread with his disciples, perhaps it makes some amount of sense to be drawn toward what the church tried to suppress for two millennia, however unsuccessfully.

I do want to stress that I was always more about the “maker of this world is incompetent and not the True God” side of gnosticism, than the “I am special and enlightened” aspect. It was largely theodicy that bothered me, the sense that this heterotrophic, entropic world which we were rapidly degrading was not one that a benevolent deity would have created. There’s a Philip K. Dick interview about killing a rat in the 1960s as synecdoche for the horrors of the world which sort of encapsulates the relevant mood here. I also should add that the variant I gravitated toward, Valentinianism, is both closer to orthodox Christianity than some and in the way it soteriologically distinguished between classes of person (although I was uncomfortable with this) is not horribly unlike the ancestral Calvinism…

In the end oddly enough it was esotericism that led me back in the direction of orthodoxy. I became very interested in various forms of platonism and Neoplatonism, and it was for this sort of Plotinian reason that I read most of the Platonic corpus sans Laws. The Neoplatonism I was reading convinced me that ritual was a necessary component of spiritual practice, and my own reflections led me to the truth that religion is after all something you do with other people. It took me a while, but eventually I started attending services at a local Episcopal church, and I’ve been more or less on the straight path ever since, to the extent that any of us can know or imagine that we are. I’m not always sure that any one of us can ever truly provide an account of ourselves that comports to reality or satisfies the lying record of memory, but this has been an attempt.

Man of Twists & Turns: The Odyssey, Auerbach, & Benardete

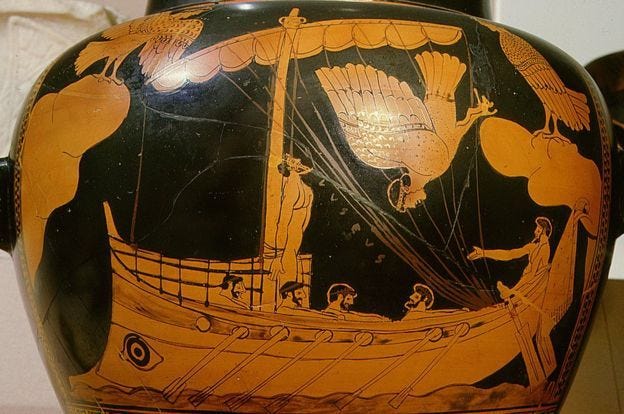

This week I reread the Odyssey in Robert Fagles’s popular translation, and some criticism of it in preparation for the beginning of John Pistelli’s Invisible College sequence on the Greeks.2 In general the Invisible College has been a remarkable project, each of its blocks almost the equivalent of a university course, minus the essays and busywork. For someone like myself, widely read but possessed of a fairly minimal formal literary education it’s been an ideal impetus to read and think through great works, some of long acquaintance, others (especially the poetry in last spring’s course) new to me. The Joyce sequence from last summer in particular was revelatory, and fundamentally altered my perspective on that greatest of Irish novelists. It’s well worth a subscription, and he’s built himself quite an impressive back catalogue for you to peruse. This wasn’t my first time with Homer’s second great poem, the foundational epic of the Western tradition, but it had been a good decade or so, and the memory was fuzzy around the edges. I had forgotten that Odysseus’ famous central oratory to the Phaeacians of his sojourns amidst the Cyclops and Circe, the Lystragonians and oxen of the sun, was such a small part of the poem overall.

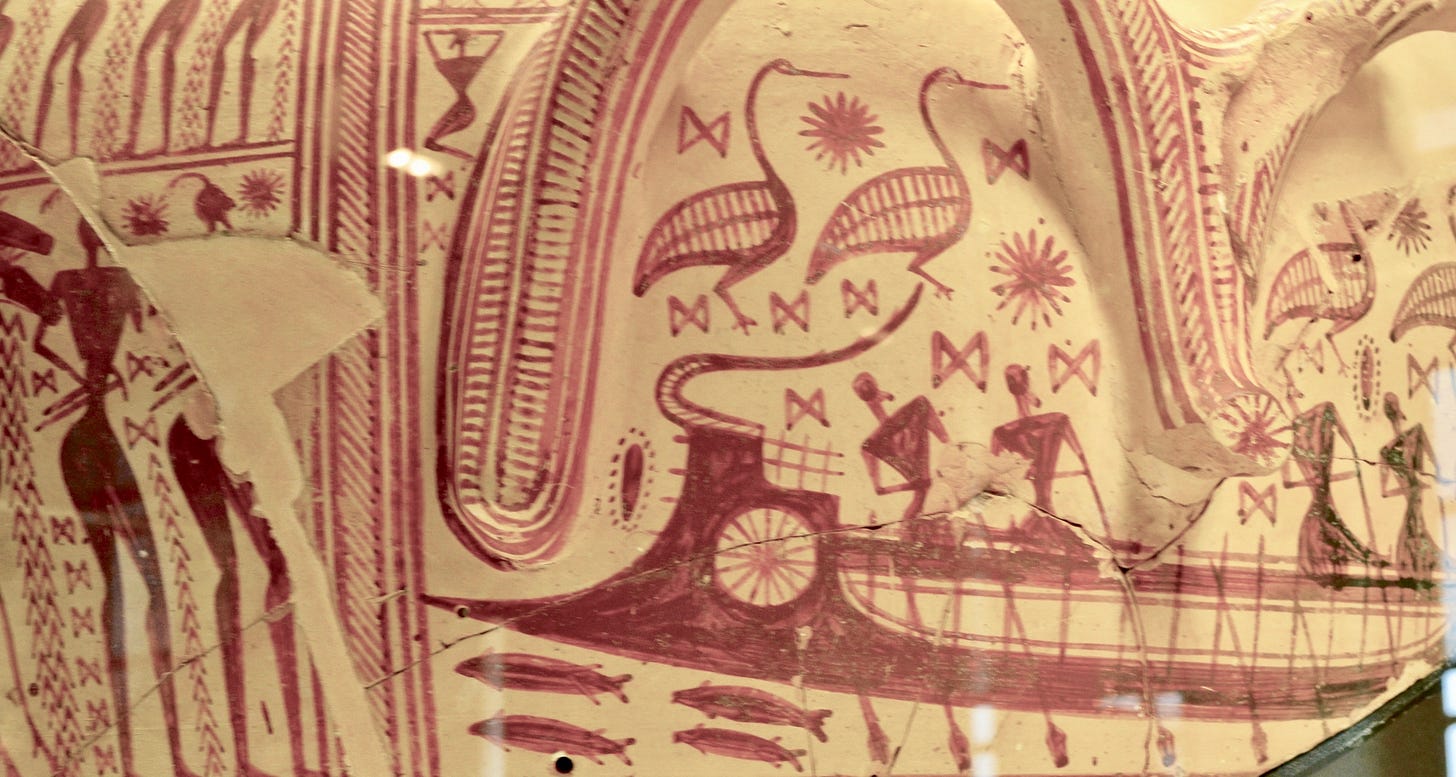

The world the Homeric poems half-describe-the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean late Bronze Age with its palace economies and great power clashes-has been something like a special interest of mine since I was 8 years old or so and saw the picture of what Schliemann dubbed the “mask of Agamemnon” characteristically getting the dating of that particular find wrong by about four hundred years. The civilization that actually attacked Troy, if such an event took place at all, appears to have been a fairly sophisticated one, capable of great feats of architecture and engineering, with complex top-down economies organized by literate scribes, but it went down in flames along with most of the known world in a pancivilizational collapse around five hundred years before Homer, whoever he was. The Homeric epics viewed in that context have an almost post-apocalyptic quality to them, Homer as the writer of a reconstituted Greek civilization composing the epics of a lost golden age across the gulf of four centuries of illiteracy bridged by the bards. This explains in part the curious anachronisms of the poems, the way their world seems so big and yet so small, the Greeks little more than scarcely civilized war bands at times. Enough historicism though, let's trot out some critics and commenters I brought along with this reading. First, a thought from Erich Auerbach’s epochal Mimesis:

The Homeric poems, then, though their intellectual, linguistic, and above all syntactical culture appears to be so much more highly de-veloped, are yet comparatively simple in their picture of human beings; and no less so in their relation to the real life which they describe in general. Delight in physical existence is everything to them, and their highest aim is to make that delight perceptible to us. Between battles and passions, adventures and perils, they show us hunts, banquets, palaces and shepherds' cots, athletic contests and washing days-in order that we may see the heroes in their ordinary life, and seeing them so, may take pleasure in their manner of enjoying their savory present, a present which sends strong roots down into social usages, landscape, and daily life. And thus they bewitch us and ingratiate themselves to us until we live with them in the reality of their lives; so long as we are reading or hearing the poems, it does not matter whether we know that all this is only legend, "make-believe." The oft-repeated reproach that Homer is a liar takes nothing from his effectiveness, he does not need to base his story on historical reality, his reality is powerful enough in itself; it ensnares us, weaving its web around us, and that suffices him. And this "real" world into which we are lured, exists for itself, contains nothing but itself; the Homeric poems conceal nothing, they contain no teaching and no secret second meaning. Homer can be analyzed, as we have essayed to do here but he cannot be interpreted. Later allegorizing trends have tried their arts of interpretation upon him, but to no avail. He resists any such treatment; the interpretations are forced and foreign, they do not crystallize into a unified

Against this piece of advice I read Seth Benardete’s great 1997 commentary on the Odyssey The Bow and the Lyre after

’s praise of Benardete reminded me that I wanted to read his two works of Homeric analysis.Benardete’s text is to my eyes complex and somewhat enigmatic, but a deeply enlightening reading via a Platonic-Straussian hermeneutic in which every element of the poem is deliberately placed and part of a larger scheme ordered by the author. I wouldn’t necessarily say that I totally grasped what he was saying, but there is to be sure an attentiveness to certain almost proto-existential themes and a sense that the poem is narrating a redefinition of humanity’s relationship with the Gods, at times seeming something almost akin to weber’s disenchantment of the world. I definitely need to read more by Benardete, and The Bow and the Lyre will definitely get a reread at some point.

Odysseus now knows something about himself he did not know be-fore. We do not know whether the gods also gain this knowledge about him. It would seem to be especially important for them to know because Odysseus's wish puts the divine law of burial at the center of his choice. Odysseus does not choose the human as such; he chooses the human that does not exist at all if there are not gods. The issue of burial, which had permeated Nestor's second account and had merged with the issue of sacrifice at the end of Menelaus's story, is chosen by Odysseus himself to be the core of his choice." His choice is not of an indeterminate future but of a completed past that would at least have made him a somebody, under divine auspices, and not the nothing, without the gods, he believes he is fated to become.

I’d somehow never thought of “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” as a gloss on the Odyssey until reading Benardete describe how Hermes speech in book 5 “makes Athena, against whom the Achaeans sinned on their journey home, responsible for the loss of all of Odysseus’s shipmates” which rather reminds me of the Night-mare-life-in-death and her watch over the mariner in Coleridge’s poem. Bernadete also liberates me from the somewhat obvious reading of poem I was taught a variant of years ago, in which Odysseus’ return represents a reestablishment of rightful patriarchal authority and proper social order after the calamity of the Trojan war and the loss of a generation of fathers resulted in rule by man-children, the suitors. This rhymes in certain ways with a set of politics on the contemporary right I’ve alluded to but never actually described in detail. It’s an obvious comparison yes, but again slightly philistine, and I’m glad I had Benardete’s book around to mostly avoid it!

Not that they're any better now really, demi-Straussian Trillingite post-centrist progressive conservative or whatever-this is sorta what the abandoned political memoir from 2023 I just reposted was about. I’m not sure what you’d call what I was on when I was 17. Inclusive dirtbag right or whatever, although what ended that phase was realizing that nobody else meant the inclusivity the way I did, and that many of these people were actually serious about the biological racism, etc.

I think the first time I read the poem was in Fitzgerald’s translation, but it was years ago now and in a class.

Fantastic stuff!

Thanks! I didn't have time to revisit Auerbach, thus I failed to mention him, but I do think his famous reading misses the implied sense of historicity in the poem—that some peoples are backward and some civilized—which, on the metaphysical level, also implies that some of the gods (Poseidon) represent the primordial and some (Athena) a humane advance. Not everything in the narrative is on the same level; e.g., there is a "romance" plane of unknown islands Odysseus visits and a "realist" level of named real places. Rather there's an implicit historical continuum moving toward Odysseus's enlightened rational governance or that of the Phaecians—patriarchal by our standards, but not absolutely, as it involves the model "marriage of true minds" of Odysseus and Penelope and the initiative and relative independence of Nausicaa.