Patricia Lockwood Leaves the Portal, Roberto Bolaño’s falcons and Valeria Luiselli’s teeth

This week I finished Patricia Lockwood’s No One is Talking About This. I definitely liked the book more than I indicated to you last week-somewhat against my will, it grew on me in the end. It has a good idea-a “weird twitter” type online comedian crashing into a real-world tragedy of the most acute and catastrophic sort-but I can’t say I’m completely satisfied with Lockwood’s execution. Were I to review it for my paying subscribers (which I might) it would probably get a score similar to the one I gave Tao Lin’s Taipei, a grudging endorsement.1 I did like the book in the end, but it feels like a slightly dishonest victory, one achieved through a certain sentimentality that I feel evil for having a problem with, because this sort of novel is really just a form of pseudo memoir, and something like this really did happen to Lockwood’s sister and niece.

Last week my discussion of the book mostly centered on its depiction of a life online, and I was somewhat critical of it in those terms. The most utilitarian account of the novel, the one that accords most with my own area of academic specialization is that we read novels to know what people were thinking and feeling in other periods. The first section of No One is Talking About This is a pretty good record of what a certain type of thirtysomething officer class personality was thinking and feeling in the Trump years. Specifically the later Trump years, the panicked online “we’re all gonna die of climate change tomorrow” years immediately pre-Covid. I was I’ll admit largely unaware of Lockwood’s prehistory as a weird twitter comedian-dear reader, I joined Twitter extremely late in the game-which explained something of the style of the first part of the book and the comedic sensibility it forefronts. There’s a kind of punchline structure common to this kind of autofiction that feels thematically appropriate to a book primarily about a sort of online comedian, but I’m not sure how funny I actually found it.

I think my most central problem with the book was simply a certain over-elegance, an over-poetic quality to the prose: a strange critique perhaps considering my complaints about similar books in the past. I’d rather my autofiction come with abundantly polished sentences than not, but still one can overdo elegant literary sentences, and by the end of the book I felt that Lockwood had done so, although your opinion may well be different.

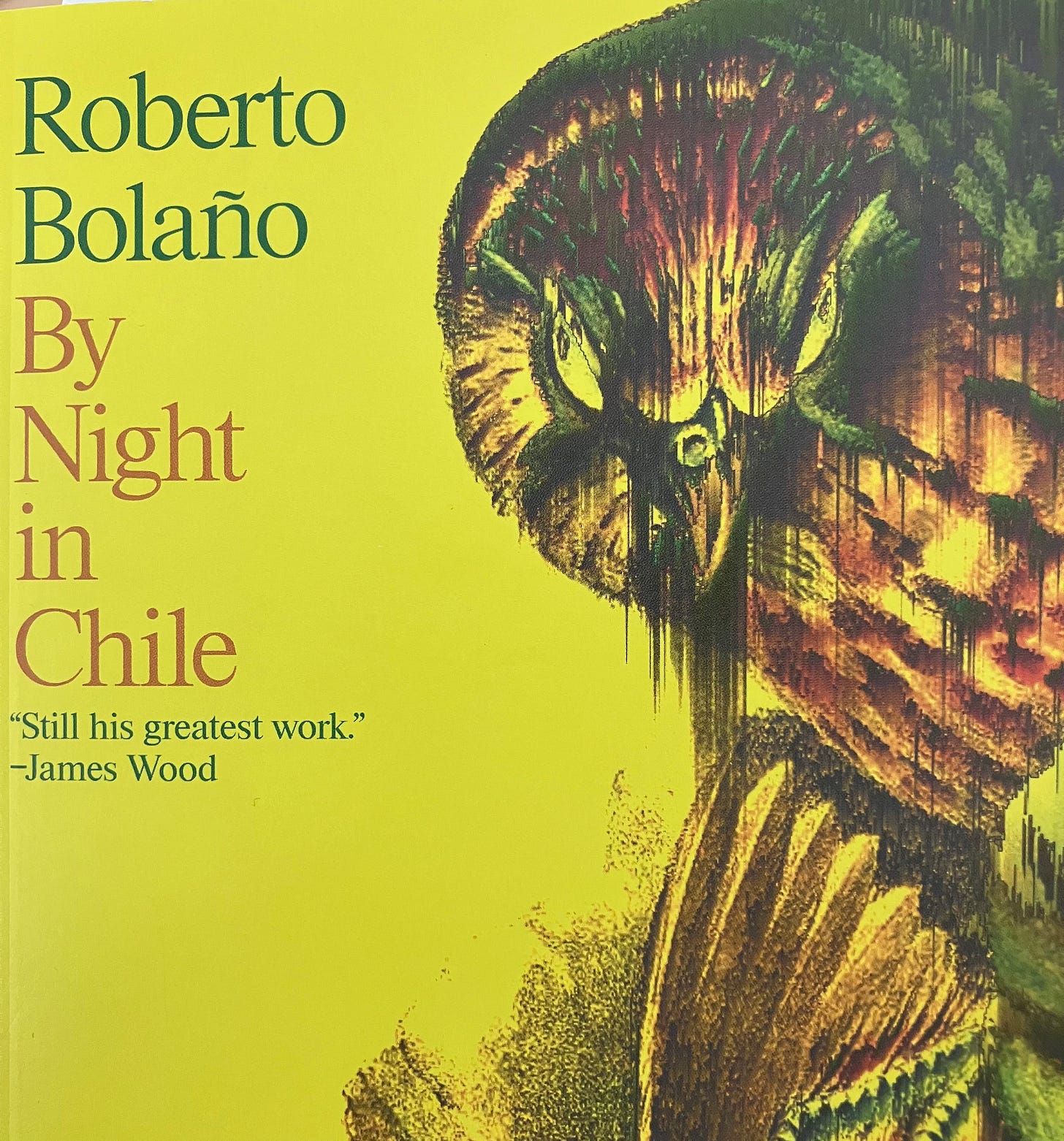

Immediately afterward I read Roberto Bolaño’s 2000 novella By Night In Chile, a wildly different reading experience to be sure. If I were employed in a teaching capacity (which I shouldn’t be, unless you want to receive a reverse engineered literary education from someone who gave one to themself) this would be a text I’d reach for in order to explain something of the gist of Bolaño.2 It’s very intense but otherwise an accessible, at times even transparent text, the dying monologue of a collaborationist Chilean priest and literary critic defending himself from the attacks of his conscience, “the wizened youth”. The overarching motif of falcons is striking and successful-to my mind for some reason reminiscent of the vast eyeglasses in the Great Gatsby- in conveying the theme of the piece, predatory birds protecting the institution of the Church by killing those whom the Church is really meant to serve, a sin in which the narrating priest is complicit.

Fr. Antonio told me he had been thinking, I have been thinking he said, maybe this business with the falcons is not such a good idea, its true they protect churches from the corrosive and, in the long term, destructive effects of pigeon shit, but one mustn’t forget that pigeons or doves are the earthly symbols of the Holy Spirit, are they not? And the Catholic church can do without the Father and the Son, but not the Holy Spirit, who is far more important than most lay people suspect, more important than the Son who died on the cross, more important than the Father who made the stars and the earth and all the universe

It’s a novella strikingly relevant to the questions of quietism and art that I’ve been throwing at you for the last few weeks with varying levels of success. The dying priest read the Great Books, read the Greeks while Chile was in turmoil under Allende and chose not to see the brutalities of the junta, and with the exception of an episode in which he was enlisted to teach Marxism to Pinochet and the rest generally keeps his head down.

The wizened youth has been quiet for a long time now. He has given up railing against me and writers generally. Is there a solution? That is how literature is made, that is how the great works of Western literature are made. You better get used to it, I tell him. The wizened youth, or what is left of him, moves his lips, mouthing an inaudible no.

What should we make of this argument, which follows the revelation that the literary soirees attended by the priest were conducted above a torture chamber where the enemies of the regime were tortured by an American intelligence agent?3 I confess that to my sensibility at least it seems obviously true. A friend suggested that this sort of thing while true, must remain secret, a kind of aesthete Straussianism, for the alternatives are either the total cessation of all literary production or a conscious, cynical evasion of personal responsibility, this is just how the world is, etc. I know what she means, but I disagree. I feel something I sometimes think might be the solution, and I’ve tried to get across something of what I mean, but even if I do have it, I’m not sure it’s something that can be taught. Even within myself I can feel it periodically breaking down and having to be rebuilt.

Each of us is the guilty priest and the wizened youth.

Finally, I began Valeria Luiselli’s 2015 sophomore effort The Story of My Teeth. I enjoyed her debut, and I’m excited to see how this one proceeds!

Listening: Pink Floyd goes punk-ish

This week I listened to Pink Floyd’s 1977 album Animals, the black sheep album of their imperial phase and an intensely important record for me. Recorded in acrimonious sessions under the influence of the burgeoning punk movement, it’s the angriest and one of the saddest Floyd albums, a concept record loosely based on bassist and songwriter Roger water’s inversion of George Orwell’s parable Animal Farm, in which late 20th century capitalist Britain is allegorically divided into three classes: Dogs (businessmen and others somewhat analogous to what I gloss as “officer class” Pigs (politicians, CEOs, Mary Whitehouse) and Sheep (everybody else.) The songs are very long (aside from the intro and outro tracks) and atmospheric. The 17-minute “Dogs” is probably the best of them, both searingly angry and genuinely sorrowful for its subjects, described in the Howl-inspired closing section as “born in a house full of pain” and haunted throughout the track by imagery of being drowned with a stone.4 I’ll certainly concede that the worldview of the album (as with most of Roger Waters’ works) is a bit juvenile & simplistic-if things were really so neat we’d have overthrown capitalism ages ago and I’d be writing this from the Union of Socialist Republics of the Americas or perhaps not writing at all-but on a level of emotion and music it comes off brilliantly.

Waltz for Stanley: on hot takes and being remembered for them

I’ve been working for about three months on a piece about the thought of the late 20th century public intellectual, novelist, music and cultural critic Albert Murray, a fascinating figure from whom I think heterodox thinkers (particularly on the center or the right, where I think much of my audience is located) could learn a great deal.5 In the process of researching Murray I’ve perused the work of one of his proteges, the cultural critic Stanley Crouch.

Crouch is today I think largely remembered for his musical tastes, specifically for his comprehensive knowledge but limited and ultimately quite traditionalist line on jazz, which was baptised into the educated white consciousness via his friendship with trumpeter Wynton Marsalis and in the 2000s by his participation in Ken Burns’ Jazz documentary. In his own day he was known as a belletrist, a hot-take haver, someone with many controversial opinions and a distinct sensibility.6 He was a combative, opinionated, and frankly often unpleasant-seeming figure, but he was perceptive, original if indebted to tradition, and always entertaining to read.

Crouch died in 2020 at the age of 74 in a curious obscurity: eulogized by many of the towering institutions of American life and yet a death largely swept away in the embers of that burning summer. Among these memorializations, perhaps the most memorable was published in Counterpunch by the novelist Ishmael Reed. It’s a pretty vicious eulogy, one clearly written by a man with some scores to settle, and if you don’t share Reed’s politics and aesthetics, there’s a lot to object to, but it’s a fascinating piece of literary gossip and worth a read. That isn’t why I bring this up though. No, what’s worth sharing-honestly whether it’s true or not-is this passage toward the end:

Those who call Stanley “Towering,” and “Great” don’t get it. Stanley didn’t want to be a critic. I can tell you that it’s easier to write about Jazz than to play it. He went to New York to become an artist. He sent me a list of books where his short stories were going to appear. They never appeared. I was one of the few who published his fiction. Stanley wanted to create–instead, he became a critic, sniping at Black writers whom he saw as his and his sponsors’ competition and kissing up to those who could do him some good. He was used by people who wanted to settle scores with prominent Black artists.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Crouch, and this eulogy lately. I thought about it, and the general spirit of it incessantly this weekend, while I was smoking a cigar and talking about Toni Morrison on Friday, and while I was travelling on Saturday. I can’t seem to get it out of my head. I plan on reading Crouch’s single novel Don't the Moon Look Lonesome? sometime soon, just to give him his due, because Reed in his venom touched something like sympathy in me for this man whose opinions about fusion, hip hop, & the works of Toni Morrison I disagree with so much.

About a month ago the anonymous friend who should probably receive a double billing with me on this substack for all that I’ve mentioned her asked if I was still working on my fictions (I was and am) and it threw me for a bit of a loop, threw me strangely back upon Ishmael Reed and Stanley Crouch. “Stanley wanted to create” Don’t I as well?

Which is my way of clumsily doing one of my revisions of the “what is this substack for” type statement I make periodically, and saying that I don’t really want to be remembered for my weird speculations and hot takes. I’ll still be around, but I want to concentrate a bit more on the aesthetic scrapbooks and thought digests that are these newsletters and my occasional reviews, and a little less on the grand essays that launch some overarching theory of politics, social relations or human types. Those are fun, and I don’t want to stop doing them entirely, but they aren’t what I want to be putting all my energy into, and if I’m going to be remembered for anything I’ve written, I’d rather it not be them.

I think I probably liked this book more than Taipei, which shows the weaknesses of a numeric rating system.

I was told so often growing up that I’d be a good English or history teacher that I think I opted not to be either, only to accidentally wind up doing something like both for you now!

This is based, incidentally, on a real episode from then-recent Chilean history, as described here:

Espinosa confirms that the story Lemebel and Bolaño recount is true. The pretty, aspiring writer was Mariana Callejas. Her husband was Michael Townley, an American who posed as a businessman but worked for Chile’s secret police. In the basement of their home, Townley interrogated leftist dissidents before they were shipped to detention centers where sometimes they “disappeared.” According to Espinosa, several important Chilean writers launched their careers at the Callejas-Townley salon, but nobody talked about the parties in public after Townley was arrested 1978. He was extradited to the US by the FBI for organizing the 1976 assassination of Allende’s foreign minister Orlando Letelier, who was killed by a car bomb in Washington, DC. By turning evidence against the men he hired for the killing, Townley brokered a reduced sentence and was eventually freed through the Witness Protection Program. His wife also agreed to testify in exchange for a reprieve. Some have said she was an informer for Chile’s military police.

Not coincidentally this is the class which Roger places himself in the closing “Pigs on the wing” Outro.

At the moment Murray’s intellectual legacy seems primarily put to use by black conservatives as a bludgeon with which to beat back the more essentialist style of thinking about race that rose to prominence on the left in the 2010s, but I think a more productive use of him might be as a corrective to the biologically racist Sailer and Hananiah strain of thought that’s risen to prominence on the more aesthetically and intellectually inclined corners of the right since 2020. His work demonstrates, elegantly and within a rubric of individual achievement and transcendence that right wingers and artists can live with, that there is no racial purity whatsoever in America, however much Americans-Black or White-may wish there to be.

I disagree with Crouch on a lot of his takes, but even when he was ultimately wrong he could land some hits. Take “Literary Conjure Woman”, his infamous 1987 pan of Toni Morrison’s Beloved in the pages of the New Republic- I think his evaluation of the book is fundamentally off, but there probably is something to his inflammatory charge that Beloved is akin to a Holocaust novel in its depiction of its traumatized, illiterate 19th-century freedmen protagonists with the language and symptoms of bourgeois 20th-century neurotics.

It seems to have been written in order to enter American slavery into the big-time martyr ratings contest, a contest usually won by references to, and works about, the experience of Jews at the hands of Nazis. As a holocaust novel, it includes disfranchisement, brutal transport, sadistic guards, failed and successful escapes, murder, liberals among the oppressors, a big war, underground cells, separation of family members, losses of loved ones to the violence of the mad order, and characters who, like the Jew in The Pawnbroker, have been made emotionally catatonic by the past.

That said, I think he’s totally off-base about Morrison herself, who was surely the greatest living American author at the time of her death, an epochal talent on a sentence-to-sentence level. I’ve read most of that corpus, and if there’s a commercial sentence in there, I’ve yet to read it.

I get the LRB which publishes Lockwood pretty regularly and over time my feelings have shifted from admiring her formidable talent with language even if the overall aesthetic is not exactly my thing to thinking "Christ, does this woman ever think of anyone but herself?" Her recent diary piece about saving her husband's life (https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v45/n04/patricia-lockwood/diary) really rubbed me the wrong way – of course I understand that it's meant to be funny and that these experiences are very surreal but it just never leaves the "how does this affect me, the main character of the universe" tone, nor does any of her literary criticism. You could be glib and say of course, that's true of all writers...but it's more true with her!

Also I love By Night In Chile, obviously, but that James Wood quote is so funny. Of course he's literally the "perfect exercises of the great masters" guy from 2666.