Stromata

mini essays about comic strips & the internet

For part of last year I ran a weekly digest of some stuff I’d read, some stuff I’d heard and a mini essay. Sometimes that content was good, sometimes it was bad, a lot of the time it was just ok. Many of those digests have been taken down due to my changing intentions for this blog and desire to escape from a certain mode of thinking about intellectual and online life in this century, but I do think some of them are worth keeping around. These are a few of my personal favorites, lightly edited.

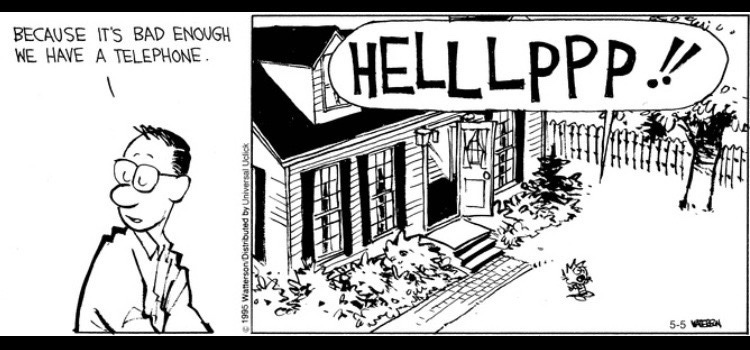

1. Because it’s bad enough we have a Telephone (8/23)

The other day I rather circuitously stumbled upon this article about Bill Watterson’s relationship to Calvin & Hobbes in what seemed to me a strange venue for it, but such are the times.1 I was particularly fascinated by the reference to the style Watterson employed in the comic as “hysterical realism.” If you haven’t heard of it “hysterical realism” is a term coined in 2000 by the critic James Wood to describe and attack the maximalist, mostly postmodern fiction of the late 20th century: Don DeLillo, Thomas Pynchon & the others, with David Foster Wallace and Zadie Smith as younger representatives of the style.

Novels, after all, turn out to be delicate structures, in which one story judges the viability, the actuality, of another. Yet it is the relatedness of these stories that their writers seem most to cherish, and to propose as an absolute value. An endless web is all they need for meaning. Each of these novels is excessively centripetal. The different stories all intertwine, and double and triple on themselves. Characters are forever seeing connections and links and plots, and paranoid parallels. (There is something essentially paranoid about the belief that everything is connected to everything else.)

For about the last year I’ve been making my way through the 48-year run of Charles Schulz’s Peanuts as it evolves from passable domestic humor leavened with sparks of genius in its early years to the sublime, lightly absurdist depression that characterizes the comic’s peak in the 60s and 70s back into passable domestic humor leavened with sparks of occasional genius. This immediately came to mind for a number of reasons: for one the post that brought this all to my attention makes this connection. More importantly it’s not a difficult one to make- Calvin & Hobbes very plainly has the same relationship to Peanuts that the work of David Foster Wallace does to that of Thomas Pynchon.2

Both Peanuts and Calvin & Hobbes are comics about children who behave like adults, comics that feature flights of fancy and elaborate fantasy worlds that only one character ever really experiences. Both have a certain subtly but also particularly suburban midwestern quality and are characterized by an essentially tragic sensibility in which things rarely go right for their characters. Both comics prominently feature male characters with striped shirts (Peanuts has several!) but now I’m just being pedantic.

Calvin thinks, speaks, and acts like no child in existence…. To the clever child, however, it becomes clear quickly that in the mind of his creator, Calvin is a tiny adult surrounded by large adults, confined to the strictures of childhood only by accident of his age and size. This is why the strip often appeals most to the lonely and unhappy, to children who do not think of themselves as such and to adults who are better thought of as children.

The way that sensibility functions within the respective strips is wildly different however. The animating philosophy of Peanuts in its best years was a kind of Christian existentialism not unlike Kierkegaard or perhaps even Paul Tillich: the world is a frequently cruel and unjust place seemingly abandoned by the God in whom the characters all believe, where goodness is often punished, and yet Charlie Brown goes right on being Good Ol’ Charlie Brown. The animating mode of Calvin and Hobbes on the other hand is divided between a pastoral idyll of dangerously philosophical sled and wagon rides down brambly Ohio hillsides and an enervating and over-connected suburban world which Calvin is both of and not: sometimes a literal worshipper of the television set, a being not unlike the children in White Noise, other times outdoorsy and wanting to escape from it all. It is striking in fact just how much Watterson’s editorial sensibility (most often given explicit voice in the person of Calvin’s dad, but present throughout the comic) seems to abominate the totalizing connection of modernity, seems to yearn for a kind of earthly solitude away from other people.3

Which put Calvin and Hobbes in an interesting place with regards to that original idea of comparing it to the big American postmodern novels, books like The Recognitions, Vineland or White Noise. Those books often either bemoaned a loss of some kind of real, local individual connection or posited-as Wood pointed out-that connection could itself provide some sort of transcendence from postmodern malaise. For Watterson though, it often seems like the idyll is riding your bike alone or walking through the woods. In Calvin and Hobbes, Hell really is other people.

2. Paywalled in the Digital Silo (10/23)

About three years ago the internet ate the world. It wasn’t exactly a surprise, the culture had been headed in that direction for a while, but the suddenness of the thing, the way it just happened sometime that March caught us all off guard. By and large this seems to have been a bad thing. Most people I think, really aren’t equipped to deal with the sort of mental bifurcation produced by having a self on the screen and a self in the world of matter and the quotidian. It made us more irritable, turbocharged the hostility of our discourse-already overheated at the best of times by that point-made us even more neurotic and depressed. It arguably produced, via opposition to the restrictions that caused the Great Onlining, the downtown reactionary hipster scene, the Alt Lit in meatspace crowd of the early 2020s, although admittedly there are other variables at play there.4

Of late (when this was originally published in October 2023) Elon has been pretty publically floating the idea of putting Xitter behind a paywall, a move that will certainly end my engagement with the platform, and may well wind up signalling the death knell for the site as the cool kids club it’s been roughly since the end of the blogging/forum era or so.5 I shed no tears for twitter, but I’m interested in what this bodes for the future of the internet. A while ago there were a bunch of arguments that social media is on its way out, or as Sam Kriss provocatively put it, the internet is already over.

In the future—not the distant future, but ten years, five—people will remember the internet as a brief dumb enthusiasm, like phrenology or the dirigible. They might still use computer networks to send an email or manage their bank accounts, but those networks will not be where culture or politics happens. The idea of spending all day online will seem as ridiculous as sitting down in front of a nice fire to read the phone book. Soon, people will find it incredible that for several decades all our art was obsessed with digital computers: all those novels and films and exhibitions about tin cans that make beeping noises, handy if you need to multiply two big numbers together, but so lifeless, so sexless, so grey synthetic glassy bugeyed spreadsheet plastic drab. And all your smug chortling over the people who failed to predict our internetty present—if anyone remembers it, it’ll be with exactly the same laugh.

There are some dissenting voices, among them Default Friend, who writes in a (sadly paywalled) Compact article of her skepticism that Twitter is going anywhere.

For writers or public intellectuals, departing Twitter is a lot like claiming you are leaving New York, except with an even lower probability of it happening. You could always go to Los Angeles—its online equivalent being TikTok and, once upon a time, Instagram—but you know in your heart of hearts that the adage “If you can make it here, you can make it anywhere” isn’t true. You couldn’t crack it in LA—you sure as hell aren’t going to succeed on TikTok. BlueSky or Mastodon, meanwhile, are like moving to Austin or Denver: Yeah, maybe, but a second-rate city is second-rate for a reason. There is “a lot happening” in Austin or Denver in the same way there is “a lot happening” on BlueSky or Mastodon. You have to go looking for it (in some cases, you have to know how to look for it), if it’s there at all, and still, it won’t be Gotham.

To a certain extent I’m with people like her. Not so much about smaller cities, and definitely not so much about Xitter, which I think is probably done for if Elon puts it behind a paywall. Don’t get me wrong: I’m sure something like it will continue to exist in a kind of warped vestigial state-not unlike 2023 Tumblr-and I expect the more masochistic journalists to endure there, paying the pittance to watch the snake eat itself as the sparks continue to fly from the fork that is Elon’s mind inside that great online microwave, but I doubt it will remain what it has been.6 Similarly I don’t really think there’s a way back to the offline world, but I do think things will change, are changing.

The great winner of the last five or so years of social media evolution seems to be Discord. You can make a discord account for free, but you have to be invited to most Discord servers, and that seems to be a feature and not a bug. Nor do I think it’s entirely coincidental that Bluesky-Xitter’s main competitor amongst the cool kids who made up the power user base-operates (at the time this was written in October 2023) on a similar walled-garden model. People want more privacy than was offered in web 2.0 social media, and without the dream of easy money from selling user data to advertisers companies are less likely to want the burden of a multitude of freeloading users. The story of my life on social media has been of exodus from the Facebook maximalism of the early 2010s to private group chats and similar entities.

The internet will be with us for the future, I suppose, but its time of being a universal hub for an online simulacra of everyday life is probably at an end. The future I suspect looks like Discord servers, looks like Urbit, perhaps looks like Substack with its self-monetization and smaller networks. I sometimes find myself wondering if there isn’t a political aspect to this as well. A lot has been written over the years about how the utopian dreams of the California Ideology and the early internet was always corrupt, at minimum blind to the ways and workings of the world, but on the other hand it was often at least an egalitarian shadow cast on the wall of the cave. From the perspective of a machiavellian technarch sitting in a doomsday vault reading Girard and Leo Strauss, what were the cultural convulsions of the 2010s but the polluting, false egalitarianism of the early internet metastasized into meatspace? I’m mostly not one of these people who thinks nothing happens in culture without the OK of some creep in Langley or Silicon Valley, but one does wonder… Whatever the cause, I suspect that long or short-term we’re all going back into online silos more or less apart from each other, which will probably be bad for the maintenance of consensus reality, but might just be better in terms of all being civil to one another. Who knows?

I have a friend who thinks that in the future everyone remaining on the internet will be queer or neurodivergent. The cishet people will get bored and leave, and it’ll just be overly online gays and persons of gender giving each other brainworms through the wires, as is tradition. I don’t necessarily agree, but as visions of the culture go I can see where he’s coming from. Almost everyone I’ve known who was logged in consistently before the great covid onlining is some kind of gay, trans, or neurodivergent. We seem perversely invested in social media-dear reader, a surprising amount still happens on facebook-even as everyone else is waning on it. I have some theories about why that might be, but I’ll mostly spare you. In spite of all this speculation, I do still have mixed impressions of what the future brings. Social media is a powerful mimetic drug, and short of some sort of national ban or other unforeseen disaster I don’t see us totally weaning ourselves off it. Still, it’s not terribly hard for me to imagine a future where socials are a bit like tobacco: seen as unsavory and the official culture discourages their use while being unable to prevent a swathe of the population from doing so anyway. Who knows, maybe we’d have online maximalist contrarians in that timeline too?

It’s worth noting that the politics of Calvin and Hobbes-while rarely overt-can be read in several different directions, unlike the mostly moderate (with periodic outbursts of grumpiness about bureaucracy in the sixties and evangelicals in the eighties) liberalism that characterized Peanuts. Watterson was anti-consumerist and pro-environment, but also deeply contemptuous of mass culture, leery of the internet, and just generally a bit of a grump. I’m not saying that Bill Watterson is a Laschian left-conservative, I think it’s probably more likely he's just a kind of crotchety baby boomer liberal, but as the American Conservative piece points out, he did study under Straussians…

Watterson does escape from Schulz-or at least differentiates himself-in a way I’m not always sure Wallace ever did (although I could be persuaded otherwise) but virtually the entire aesthetic of C&H barring the Spaceman Spiff fantasies is present inside Peanuts. Then again, what are the Spaceman Spiff segments but Snoopy’s dream world visualized from his perspective, rather than the solidly if sometimes a bit loopy midwestern realist frame that Schulz drew from?

This stuck out to me far less reading as a child growing up in the countryside who loved the outdoors and solitude amongst nature, but seems especially notable as an adult who spends so much time staring at either books or computer screens.

I’m almost certainly not the person to write about this, but I’m fascinated by the shift between the very appreciative urban elite white racism of the late 2010s that was very into black music and culture as prestige object/proof of one’s culturedness, and the classically “white psyche perceiving itself as under siege by black lumpenproletariat” racism that characterizes many of those same circles in the 2020s, seemingly as a result of the summer 2020 uprisings activating latent sentiments and fears.

I did wind up mostly abandoning Twitter, less for these reasons and more because I find its unending stream of negativity intensely corrosive.

Five months on I would say this has been largely vindicated.

This is a fantastic pastiche. Bravo!