Hi! Now that my Major Arcana review is out and the Cantos project is finished, I’d like to get back to doing more regular weekly posts. This week, some musings on the Bible, secondary literature, and Mahler

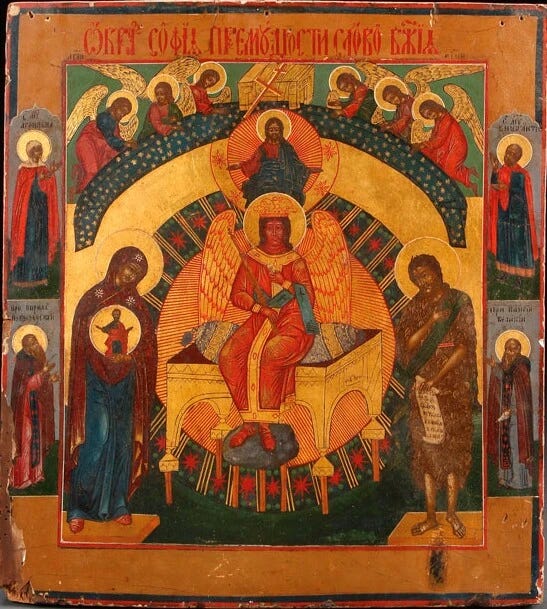

I've been reading the book of Sirach, one of the very few "new to me" parts of the bible having been excluded from the protestant canon and eventually expelled from the English bible altogether in the nineteenth century. From a historical persp ective this is a fascinating book, a collection of sayings bookended and occasionally interrupted by invocations and praises of wisdom personified in a female form, Sophia.

All wisdom comes from the Lord and is with him for ever.

The sand of the sea, the drops of rain, and the days of eternity-who can count them?

The height of heaven, the breadth of the

earth,

the abyss, and wisdom-who can search them out?

Wisdom was created before all things, and prudent understanding from eternity.

5The source of wisdom is God's word in the highest heaven,

and her ways are the eternal commandments.

6The root of wisdom—to whom has it been revealed?

Her clever devices-who knows them?

The knowledge of wisdom—to whom was it

manifested?

And her abundant experience who has understood it?

There is One who is wise, the Creator of all, the King greatly to be feared, sitting upon his throne, and ruling as God.

The Lord himself created wisdom in the holy

spirit;

he saw her and apportioned her, he poured her out upon all his works.

She dwells with all flesh according to his gift, and he supplied her to those who love him.

Sirach 1:1-12

This feminine embodiment of wisdom has a substantial afterlife in the western esoteric tradition, especially within the gnostic systems, within which she occupies a position somewhat analogous to Adam & Eve within orthodoxy-the ultimate progenitor of the fallen world we inhabit. This sent me reaching for Jonas & Jung, esp. Answer to Job, which I mentioned in passing last year, and which I am informed by

is having something of a moment in our time.The pneumatic nature of Sophia as well as her world-building Maya character come out still more clearly in the apocryphal Wisdom of Solomon. “For wisdom is a loving spirit,” “kind to man.” She is “the worker of all things,” “in her is an understanding spirit, holy.” She is “the breath of the power of God,” “a pure effluence flowing from the glory of the Almighty,” “the brightness of the everlasting light, the unspotted mirror of the power of God,” a being “most subtil,” who “passeth and goeth through all things by reason of her pureness.” She is “conversant with God,” and “the Lord of all things himself loved her.” “Who of all that are is a more cunning workman than she?” She is sent from heaven and from the throne of glory as a “Holy Spirit.” As a psychopomp she leads the way to God and assures immortality.

Of course the greatness and the trouble with Jung is that he is so Key to All Mythologies about western theological & esoteric systems. The good in this is that he takes mythology, theology, & the various subterranean traditions of western mysticism far more seriously than one such as himself who was engaged in the foundation of one of the intellectual professions of the twentieth century would otherwise be expected to. On the other hand this leads to the aspect of Jung that one might call his charlatanism or perhaps more demotically his woo-woo, “Mayan space aliens built the pyramids”-adjacency. Answer to Job has a fascinating thesis, one complicated if not actually refuted by the subsequent seventy-five years of western history, namely that the monotheistic mind of the west struggles for being unable to integrate woman and evil into the person of God.

In Triumph of the Therapeutic Rieff remarks somewhere that Jung is a profoundly protestant thinker, and this book both slightly refutes and confirms that point. In the one hand Jung counts as a deficit the Reformation’s ejection of the Virgin Mary from Christianity’s celestial family, celebrating pope Pius XII’s promulgation of the assumption of Mary, while on the other his exegesis leads him to a certain literalism in assuming that John of Patmos is identical with John the apostle.

The Eternal Feminine draws us Upward: Mahler’s 8th Symphony

This week I found myself giving a spin to two different versions of Gustav Mahler's Eighth Symphony, colloquially (and apparely to the dislike of the composer known as the "Symphony of a Thousand” due to the large number of personnel required for a performance. A massive hour+ two-part choral piece blending a ninth century Christian hymn in Latin and the ending of Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe's Faust Part II, it has slowly over the last two years become one of my favorite peices of music. Dedicated to his wife Alma, with whom he had a troubled but adoring relationship, and expressing an optimism about humanity and the future which seems quite distant from us today, it is a work that polarizes. It is, as noted difficult to pull off-I reccomend the 1971 George Solti & 1966 Leonard Bernstein recordings, at least amongst those that I've heard-and listening to it one often wonders how well it fits with the world that we have built since Mahler's death from endocarditis in early 1911. There is a certain antediluvian, even nearly Edenic quality to the optimism of the work, of much of this late Victorian or Edwardian romanticism, created as it was in a country that would not exist a decade later, by a man who would have risked extermination or been forced into exile if he had enjoyed a ripe old age.1 We are liable, as George Steiner writing In Bluebeard’s Castle put it, to find it baffling.

The apotheosis at the close of Faust II, Hegelian historicism, with its doctrine of the self-realization of Spirit, the positivism of Auguste Comte, the philosophic scientism of Claude Bernard, are expressions of the same dynamic serenity, of a trust in the unfolding excellence of fact. We look back on these now with bewildered irony.

Some held that even in 1910 it was impossible. As uncharacteristic as it is within Mahler’s pessimist-leaning oeuvre, the Eighth has always had its detractors. Some argue that the two halves do not cohere, others assert that the symphony is, to borrow a famous line from the bard, “full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” The great Frankfurt school philosipher Theodor Adorno’s famous dissent on the Eighth considers it an empty spectacle:

The end here is that no end is any longer possible, that music cannot be hypostatized as a unity of actually present meaning.

Such hypostasis is pursued by the official magnum opus, the Eighth Symphony. The words "official" and "magnum opus" (Hauptwerk) indicate the vulnerable points, the genre chef d'oeuvre, Puvis de Chavannes, the ostentatious cardboard, the giant symbolic shell. The magnum opus is the aborted, objectively impossible resuscitation of the cultic"It claims not only to be a totality in itself, but to create one in its sphere of influence. The dogmatic content from which it borrows its authority is neutralized in it to a cultural commodity. In reality it worships itself. The spirit that names the Hymn in the Eighth as such has degenerated to tautology, to a mere duplication of itself, while the gesture of sursum corda underlines the claim to be more. What Durkheim imputed to religions at about the time the solemn festival performances from Parsifal to the Eighth Symphony were coming into being, that they were self-representations of the collective spirit, applies exactly to at least the ritual art-works of late capitalism. Their Holy of Holies is empty. Hans Pfitzner's jibe about the first movement, Veni Creator Spiritus: "But supposing He does not come," touches with the percipience of rancor on something valid.2

Still, the dove continues to fly even after the flood, though our hopes may be dashed, though we continue to do our best to destroy whatever beauty may be extant, still the spirit descends to our abjection. The cliched adjective about the finale of the piece is “cosmic” but there really is something indescribable about the way it builds and builds only for the orchestra-organ excepted-to drop out for a brief moment as voices from what Hugh Kenner once memorably described as “a gone world” sing the final chorus.

Alles Vergängliche

Ist nur ein Gleichnis;

Das Unzulängliche,

Hier wird’s Ereignis;

Das Unbeschreibliche.

Hier ist’s getan;

Das Ewig Weibliche

Zieht uns hinan.

Adorno, Theodor W. Mahler: A musical physiognomy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Jung, C. G. Answer to Job. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1973.

Steiner, George. In Bluebeard’s castle: Some notes towards the redefinition of culture. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1971.

As with Kafka, it is somehow-despite both men’s vogue in the traumatized prosperity of the late twentieth century, despite that Kafka spoke of emigrating to Palestine and Mahler was in New York conducting when his fatal illness began-nearly impossible for one to imagine them surviving into a world after the Second World War, after Auschwitz.

I'm very half and half on Adorno's aesthetics. Certainly one sees what he means much of the time (maybe not so much on his thoughts on Jazz) and there is merit to his vision of a redemptive fragmentation-something like this is what makes the best hip hop production great-although, given the recent political turn and antics of Kanye West it may perhaps be said that it did not have the antifascist effect that Adorno seemed to hope that it would. On the other hand Lukács was not entirely wrong in the preface to the 1967 edition of his Theory of the Novel to see a certain aesthetic conservatism in the general disposition of the Frankfurt school. Their sense that by renouncing the absolute, by shying from the vision of x, that we can avoid the calamities that befell the globe in the first hald of the century and obey that new categorical imperative, never again Auschwitz, has proven itself a troubled goal. On the one hand I would myself cast eyes askance in the direction of one who said that which I have just proclaimed, especially since nobody who makes these arguments ever seems to grasp that there are also economic reasons why this sort of thing took place. Not everything, and indeed much that happens in this world occurs without the consent of this or that intellectual in this or that institution. On the other does seem to me that the absence of such a vision has proved destructive in a sort of Platonic-psychological regard, but this is a topic on which my thoughts are probably too self-contradictory to be worth being definite about. Next week I may have an entirely different perspective about all this.

Something fascinating about Sirach is that his version of Adam and Eve doesn't contain any Fall. Since he praises Wisdom so highly, why would the acquisition of wisdom be a transgression? In Sirach, God simply tells Adam and Eve about good and evil. I prefer this chiller God.

In the Catholic Bible, Ecclesiasticus is the first time that Adam and Eve are mentioned after Genesis, which points to the fact that the myths in Genesis were actually incorporated at a later date, inspired by Babylonian myths after the exile.

In the Nag Hammadi library, Sophia sometimes appears as a part of a sort of accordion of female salvational characters. In some myths she even splits it two: the perfect Sophia in the pleroma, and fallen Sophia, corrupted by the lion-headed serpent she gave birth to. In a full inversion, Wisdom ends up being the creature that brought about the Fall!

I agree that Mahler after Auschwitz is unimaginable—and how much moreso for Strauss, who died one week before Adenauer took power in West Germany.