Hi! As promised, the post for Bloomsday. It’s part new meditations on this greatest of 20th century novels, part remix of previously published work, with some new quotations, hermeneutics, and shout-out to a few helpful interlocutors whose essays, reviews or comments have helped me think about Joyce.

On this most holy literary day we gather to sing the praises of the great book of modernity. For more than a century James Joyce’s Ulysses has stood as the roman par excellence-the pinnacle of the western novel, never unread, never undiscussed, even as it remains a forebodingly challenging book to actually read, surely the most difficult must-read novel in the canon. This is my first and in some respects primary objection to the contemporary reception of Ulysses- we have become altogether too comfortable with it. The line on Ulysses most frequently encountered in our era is, to borrow from

: "It's nothing really -- just a touching story about a marriage, about a guy going for a walk around Dublin -- really it's easy if you think about it!” which seems to do both book and reader a disservice. It isn’t unreadable by any means-it’s probably the most enjoyable and easily digestible sixhundredpagehalfwritteninaprivatelanguageorstreamofconsciousnesswithoutpunctuationordiscernablechapterbreaksdependingontheeditionyourereadingofcourse book in the roster of the English language, and this is because the critics aren’t wrong that underneath all the drunkenness and meditation on suicide and public masturbation and foreboding literary devices employed by Joyce it is basically a sort of middlebrow nineteenth century domestic novel. On the other hand, Ulysses is a tough nut to crack on the first go-round, and some of its contemporary reception strikes me as somewhat dishonest on that point. There is profit in going back to the initial readers, people like Erich Auerbach:Still clearer and more systematic (and also, to be sure, much more enigmatic) are the symbolic references in James Joyce's Ulysses, in which the technique of a multiple reflection of consciousness and of multiple time strata would seem to be employed more radically than anywhere else. The book unmistakably aims at a symbolic synthesis of the theme "Everyman." All the great motifs of the cultural history of Europe are contained in it, although its point of departure is very specific individuals and a clearly established present (Dublin, June 16, 1904). On sensitive readers it can produce a very strong immediate impression. Really to understand it, however, is not an easy matter, for it makes severe demands on the reader's patience and learning by its dizzying whirl of motifs, wealth of words and concepts, perpetual playing upon their countless associations, and the ever rearoused but never satisfied doubt as to what order is ultimately hidden behind so much apparent arbitrariness.

Or Jorge Luis Borges, whose admission in his contemporary review that he had not finished the book is an admirable reminder that it is not just we barely-literate plebians who struggle.

I confess that I have not cleared a path through all seven hundred pages, I confess to having examined only bits and pieces, and yet I know what it is, with that bold and legitimate certainty with which we assert our knowledge of a city, without ever having been rewarded with the intimacy of all the many streets it includes.

In the preface to his 2012 essay collection The Adventure of French Philosophy, Alain Badiou identifies two primary strands within the postwar tradition of Francophone thought, one identified with thinkers such as Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, and Deleuze, a "philosophy of vital interiority, a thesis on the identity of being and becoming; a philosophy of life and change." The other tendency, identified with Lacan, Althusser, & Levi-Strauss, he describes as "a philosophy of the mathematically based concept: the possibility of a philosophical formalism of thought and of the symbolic.” A very similar dialectic is found throughout Ulysses, and indeed, thinkers as far apart as Derrida and Lacan saw themselves as philosophizing in the style of Joyce’s great work.

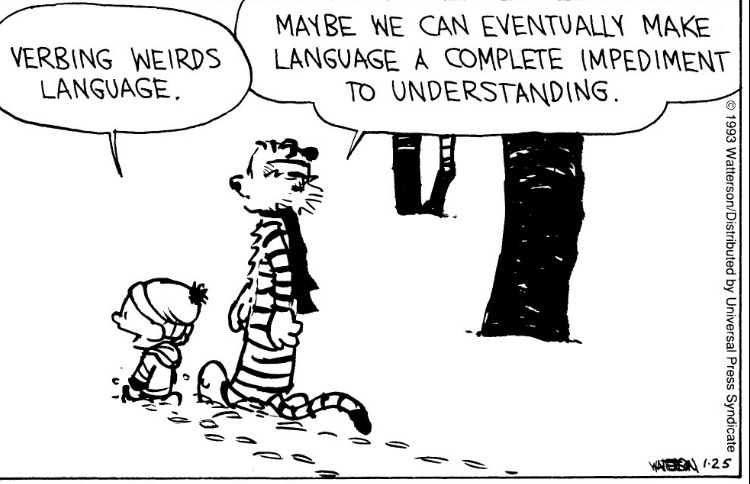

Because it clearly is a finished masterpiece of the highest order, I’m not sure how often it is appreciated that Joyce’s vast novel is fundamentally a transitional work, bridging the middle and late phases of his oeuvre. This begins in the Tolstoy or Ibsen-esque realism of the various stories in Dubliners before becoming increasingly experimental over the next two books, which are increasingly marked by formal devices and difficult diction & excessive punning. Eventually the language, to quote Hobbes speaking for Bill Watterson, becomes “a complete impediment to understanding” and thus Finnegans Wake is pretty much unreadable without a near-religious devotion to Joyce’s project, which I do not possess.

Politically, the book is somewhat multifaceted: “de- or post-colonial,” to use a few anachronistic terms, but sharply critical of actually existing Irish nationalism’s parochialism and the Hellenizing impulses of Mulligan and the ludicrous Haines. For much of the period in which Ulysses was written a resident of Trieste, at that time a city in Austria-Hungary, Joyce blended the cosmopolitanism of that multinational, late imperial milieu with the Dublin of his youth for the setting of this epic of modernity. The character of the dual monarchy memorialized by Robert Musil’s Der Mann Ohne Eigenschaften as Kakania, deeply multifaceted and multilingual, dysfunctional and acrimonious and yet also sophisticated and worldly, backward in some ways and also a center of modernism in its early form, is thus in a subterranean way commemorated almost as much as turn-of the century Dublin. Finished and published in the years following the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires and amongst the various wars of ethnic cleansing and national purification fought among the peoples of the Mediterranean, it seems perfectly understandable that the most brutal satire of the novel is reserved for the Irish nationalists in the “Cyclops” section. Certainly living under an imperial regime is bad for your health-a drunken Stephen is nearly taken in by British colonial authorities for breaking a chandelier in a brothel, and the state of Ireland as portrayed in the novel is not a positive one. Still, Joyce is remarkably open-eyed about what will follow empire. The characteristic of the National regime that will succeed empire is rule by the citizen, rule of national purification.

And says he:

—Mendelssohn was a jew and Karl Marx and Mercadante and Spinoza. And the Saviour was a jew and his father was a jew.

Your God.

—He had no father, says Martin. That'll do now. Drive ahead

—Whose God? says the citizen.

—Well, his uncle was a jew, says he. Your God was a jew.

Christ was a jew like me.

Gob, the citizen made a plunge back into the shop.

—By Jesus, says he, I'll brain that bloody jewman for using the holy name. By Jesus, I'll crucify him so I will. Give us that biscuitbox here.

On the other hand the book obdurately refuses to have a politics beyond reformist liberalism-revolution on the due installments plan, as Leopold Bloom puts it. This was unappreciated by early readers, who seemed to assume that as almost every other major modernist had some sort of extremist politics, so must have Joyce. Here we see Lionel Trilling making this mistake:

if on the other hand we name those writers who, by the general consent of the most serious criticism, by consent too of the very class of educated people of which we speak, are to be thought of as the monumental figures of our time, we see that to these writers the liberal ideology has been at best a matter of indifference. Proust, Joyce, Lawrence, Eliot, Yeats, Mann (in his creative work), Kafka, Rilke, Gide—all have their own love of justice and the good life, but in not one of them does it take the form of a love of the ideas and emotions which liberal democracy, as known by our educated class, has declared respectable.

—We can’t change the country. Let us change the subject

There’s a way in which the novel is unsuccessful because of this lack of any alternative to the uncontrolled chaos of liberal modernity, embodied in form as the dialectic between humanistic narrative and machinic formalism: Joyce cannot make it cohere any more than Ezra Pound could. On the other hand, there’s a way in which this is why Ulysses is the book of the 20th century-and ours. One suspects that if it did cohere it might be something like Pound or the other modernists, some totalizing horizon re-enclosing the world in the vision of the Gesamtkunstler’s dubious politics. The best ambivalent-to-negative reviews of the novel suggest that Joyce wound up doing just this anyway, that his cosmopolitan vision has become the world we inhabit today, a world in which we have no choice but to be free.

’s 2022 essay on the book makes this case, arguing that something like “Oxen of the Sun” or “Ithaca” is in essence already AI:If technology in the form of Joyce’s inorganic formalism is allowed to overwrite the human, is permitted to encode by the algorithm of Joyce’s arbitrary conceits the most intimate matters of growth and desire, then the New Bloomusalem was doomed from the start to become the loveless technocracy that is more and more our world.

Still, although the second half is quite a bit weaker than the first, and somewhat over-devoted to aforementioned machinic formalism, the spirit is still visible in the spaces between the cogs. The humane parts of Ulysses shine through, at least for me, in this moment, in this place.

The closing “Penelope” section is surely the best part of the book, perhaps of Joyce’s corpus overall. A truly virtuosic performance, Molly Bloom is one of the most strikingly realized, most alive characters in the anglophone literary canon. I am sometimes so close to joining Merve Emre in unqualified praise, praise which does probably constitute a betrayal of something or other:

It is probably a betrayal of the feminist literary tradition to pronounce the final episode of “Ulysses,” “Penelope,” the best—the funniest, most touching, arousing, and truthful—representation of a woman anyone has written in English. But it is, and the eight long, unpunctuated, and outrageous sentences of Molly Bloom’s silent monologue make much of the feminist canon look like a sewing circle for virgins and prudes.

Like the closing of Goethe’s Faust and Mahler’s 8th, Ulysses closes with the apotheosis of the divine feminine. Das Ewig-Weibliche Zieht uns hinan. And yet there is a certain complication. As Marx famously proclaimed that Hegel’s system should be stood on its head, Molly Bloom is a Goddess-of-this-world, of sensuality, of the body. Above all else, of sex.

I had to get him to suck them they were so hard he said it was sweeter and thicker than cows then he wanted to milk me into the tea well hes beyond everything I declare somebody ought to put him in the budget if I only could remember the 1 half of the things and write a book out of it the works of Master Poldy yes and its so much smoother the skin much an hour he was at them Im sure by the clock like some kind of a big infant I had at me they want everything in their mouth all the pleasure those men get out of a woman I can feel his mouth O Lord I must stretch myself I wished he was here or somebody to let myself go with and come again like that I feel all fire inside me or if I could dream it when he made me spend the 2nd time tickling me behind with his finger I was coming for about s minutes with my legs round him I had to hug him after O Lord I wanted to shout out all sorts of things fuck or shit or anything at all only not to look ugly or those lines from the strain who knows the way hed take it you want to feel your way with a man theyre not all like him thank God some of them want you to be so nice about it I noticed the contrast he does it and doesnt talk I gave my eyes that look with my hair a bit loose from the tumbling and my tongue between my lips up to him the savage brute Thursday Friday one Saturday two Sunday three O Lord I cant wait till Monday

Ulysses is in many ways despite appearances, not a lit bro text, not really a masculinist work at all1, but I do sometimes think I detect in Molly’s lusty pronouncements—recognizable as they are, as true to life as they seem—the voice of the phallus as ventriloquist praising its own prowess. It’s not quite fair to the character or to Ulysses, but I can’t shake the impression that somehow Joyce provided the original model that like a photocopy, diminishing in fidelity with every iteration, eventually produces the inert woman as receptacle for male desire who mars the work of many of the otherwise great 20th century male novelists who follow him.

For now, that’s all there is, although Ulysses is a book, and Joyce an author about and of whom one is never really done thinking and saying. Happy Bloomsday all!

I’ve always thought that this implicit argument-which centers around the juxtaposition of Stephen and Bloom with Buck Mulligan and Blazes Boylan—doesn’t quite scan to the modern reader because of where Joyce winds up in the roster of 20th century literary masculinity, which is to say, as himself the ancient father, the distant hectoring precursor.

I like the whole comment but I *love* the observation about the phallus as ventriloquist, that's really insightful.

Although in defense of Joyce's male heirs, Coetzee managed to imagine himself into a female novelist who has become famous for a book re-writing Ulysses from Molly's point of view. Elizabeth Costello is a feat of ventriloquism worthy of the ancient father: a new painting in the style of the master, not a photocopy. I hadn't thought about this but J. M. is resisting exactly the tendency you describe.

I have seen Joseph Strick’s ULYSSES - in 1977 at UCLA - survey of Modern literature class