It must be said of Ezra Pound that for all his demerits he had a remarkable gift for mixing the elevated and the demotic, shifting from some minutiae of European history into the griot of contemporary America and back again, sometimes in the same passage.

He shares this gift with several of his modernist contemporaries, and among later authors most notably with Thomas Pynchon. Obviously as with so much about Pynchon the question of influence is an enigma-there will inevitably be a tell-all when he croaks unless the family keeps up the game, but I'm most intersted to know what he had read, the question of who he was into etc. I think there is probably some influence from the Cantos, if nothing else perhaps they served as a warning not to ever go too far into the conspiracy theories he played with, not to allow himself to be eaten by them the same way Pound did.1 This Decad marks the point at which the economic theories become absolutely dominant and impossible to ignore. Pound's railing against Usura, by which he doesn't exactly mean what we mean by usary, but also certainly doesn't *not*. From The Pound Era:

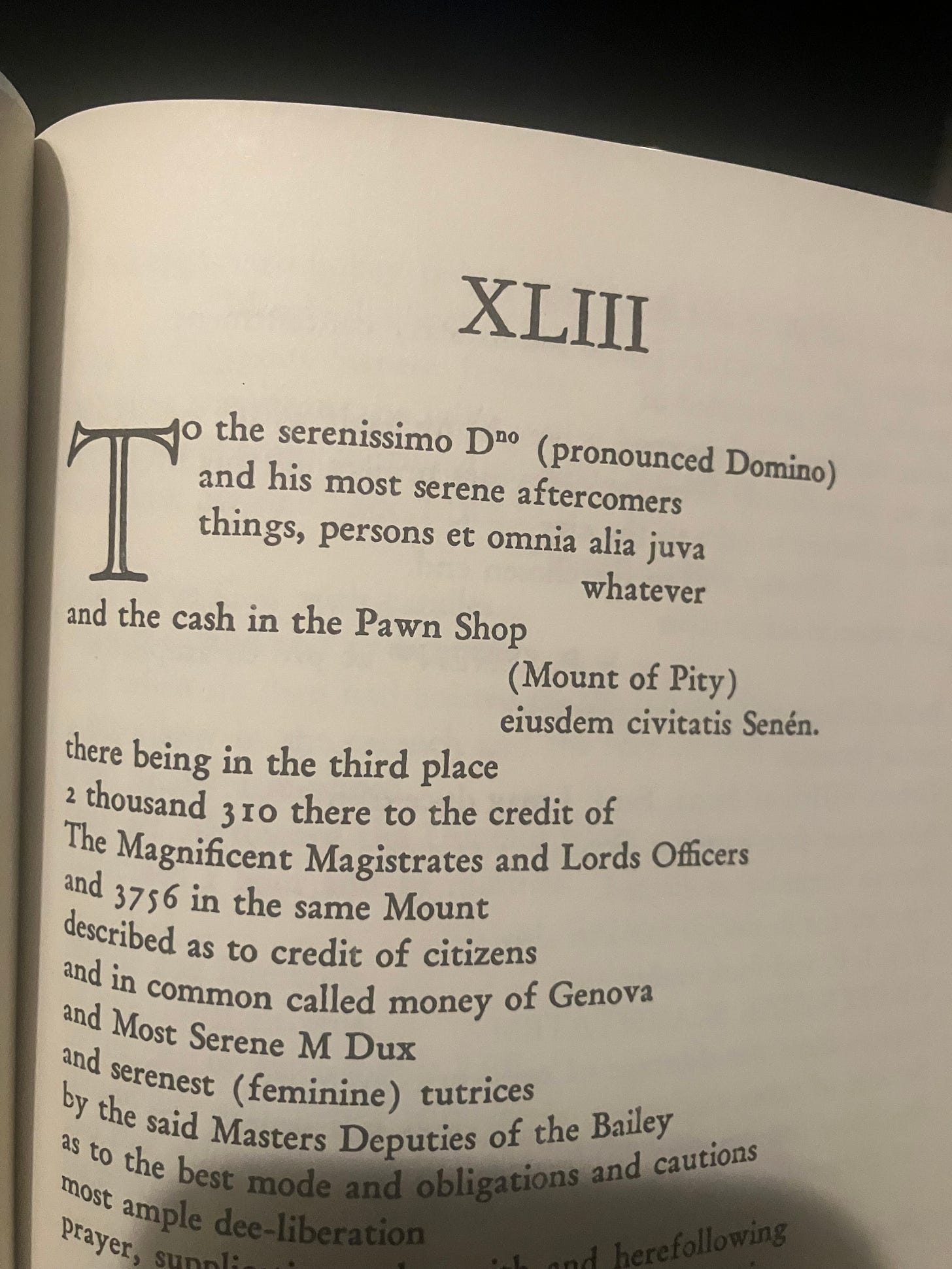

For just here we encounter a kind of difficulty that will bulk larger and larger as the Cantos progress. The theme that unites the Monte dei Paschi Cantos to the theme of fertility, and will link the contrasted Bank of England (Canto 46) to themes of perversion and illusion, is easily stated. The Monte's capital did not conceal a bottomless debt for borrowers to fill, but was guaranteed by income from the city's grazing lands toward Grosseto, 10,000 ducats per year, representing the natural increase of the sheep. "And," wrote Pound explaining this in 1935, " the lesson is the very basis of solid banking. The CREDIT rests in ultimate on the ABUNDANCE OF NATURE, on the growing grass that can nourish the living sheep.

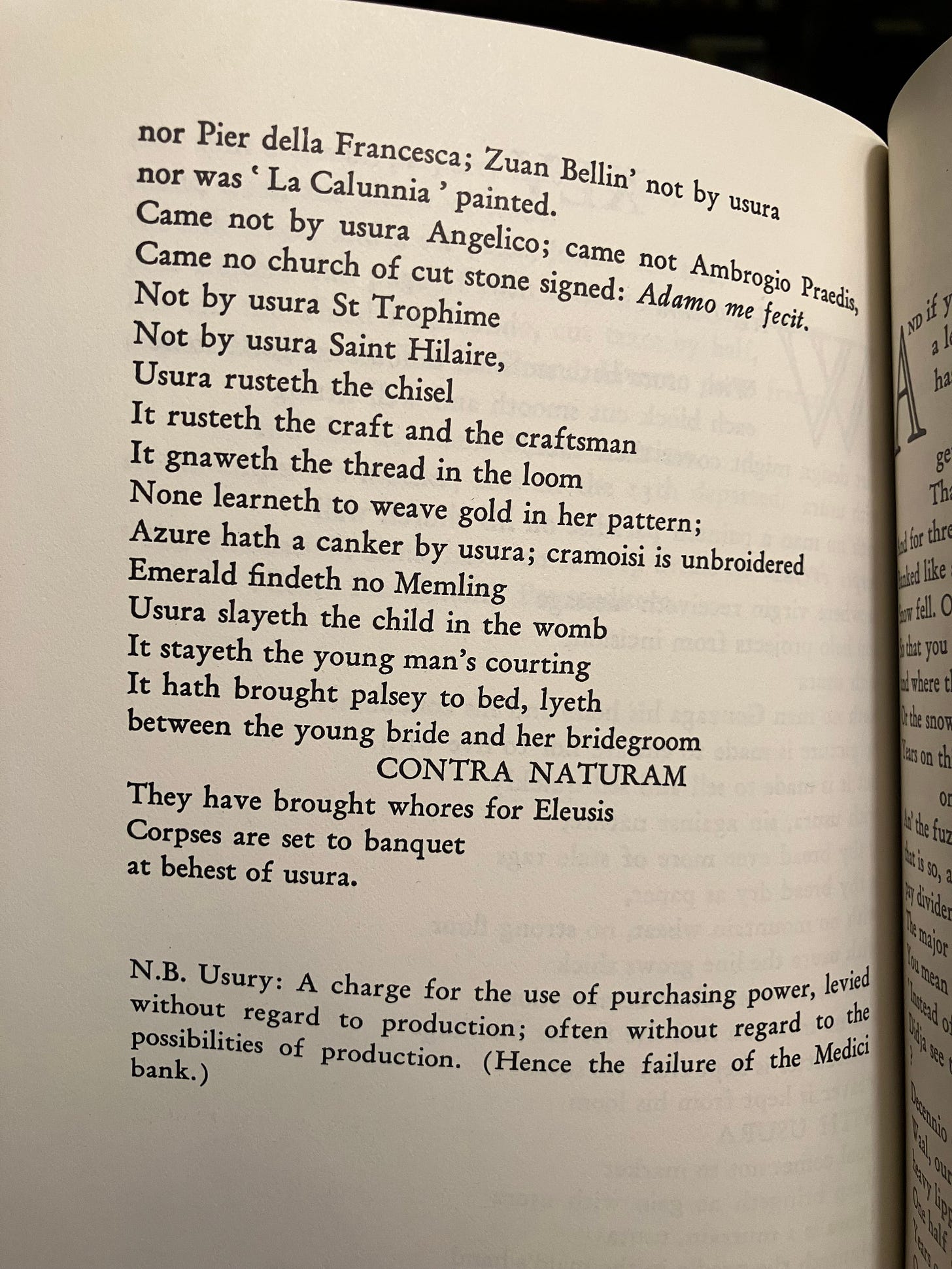

A crucial canto lays out the thesis and with the phrase CONTRA NATURUM connects to a more frequently read writer of Italian cantos’ placement of sodomites and userers in the same level of hell. The antisemitism is making itself known in a much more obvious way now, the economic theme more and more the only thing the poem appears to be about. Kenner again:

The Rothschilds, who had defeated Napoleon, were long-standing archetypes: despised outsiders who had come to master those who snubbed them, even as the boy who became Sir Basil Zaharoff (the "Metevsky" of the Cantos) was to hate the British all his life because a Britisher kicked him in Constantinople (18/80:84). Hitler jailed no Rothschilds, and Pound thought that the poor Jews whom German resentment drove into concentration camps* were suffering for the sins of their inaccessible coreligionists.

It begins to remind of the material I've already read in the Pisan Cantos, but Mussolini has yet to appear. The Italian history would be truly mystifying without annotations. I'm using the University of California's Companion by Carroll F. Terrell, which speaks of the present section as the "Leopoldine Cantos" Pound quotes from the correspondence of Napoleon for the sources of much of this material, as well as appropriating, some episodes from the diaries of John Quincy Adams. Incidentally the writings of Charles are on my list of things I need to read with half the western philosophical canon and most of DeLillo. There's a suggestion of a Dolchstoßlegende against Napoleon by the Rothschilds, and yet another return to the Odyssey for what is again something of a highlight.

I won't bore you with this observation every time, but it is occurring to me why one would consider it a tragedy that a poetic mind of Pound's caliber devoted the last thirty years of his life to this vast monstrosity, I've read enough of the later bits to have an idea that this isn't quite fair to the poem, but it would be wrong not to point out the note of exasperation which has settled onto my weekly ritual of reading the next part of the Cantos. What can really be said though? This 16 part of the intrigue of reading the poem, the reason I compared it to Cerebus on one occasion. It's not quite the same, because the worms had already eaten into Pound’s brain by the time the poem begins, but the spirit is close enough to be worth analogizing. Unless you are yourself invested in these economic theories much of this material is only saved in terms of interest by the occasional flurries of delirious wordplay and frequent reference, and even that is often comprehensible only with outside aid. Again, I don't want to say this every week, so I promise this will be the last time, (maybe, at least until I make some sort of conclusive statement at the end) but there is a reason that we read Ulysses and mostly do not read Pound’s epic unless one is either a specialist or particularly interested in modernist literature. There are those with doctorates in modernism who do not read the Cantos, and I can't particularly say that I blame them. Next week however we will be taking a look at the Chinese history cantos, which promise to be somewhat more interesting, at least from my perspective. Until next time!

How different really, is Pound's effort to explain how Usura caused the great war from the grail-quest of any given, Pynchon protagonist, from an Oedippa or a Doc Sportello? Sure the valance is different owing to the postwar setting and certain sympathies on his part, but the effort to impose or discover some sort of hidden meaning is the same. Pynchon's darkest moments suggest that the effort to discover truth is just the flip side of imposing it at the end of a billy club. One of the points of Inherent Vice is that Bigfoot and Doc aren't as much unlike as each would like to think

Good post as always, I hope this project isn't driving you too much to madness. You could always take a break and do "Cathay" or something. I can't believe a dismissive "whatever" is that old. This is like when I discovered Significant Capitals (as in "I don't want to go, but I feel like it would be kind of a Big Deal if I didn't") as a literary device in Dorothy Parker. I thought it first showed up in DFW or Franzen or something.