To Lead back to Splendor Part IV

Blessed relief, the Chinese History Cantos, and secret wars of the spirit

It was only last summer, while doing some work on S.T. Coleridge that I discovered the complete rapport between the arts and the secret societies. I was flabbergasted. Coleridge has directed me to Porphyry, apropos of The Ancient Mariner. At the same time T.S. Eliot’s essay on Byron had hinted at a hook-up between Byron’s The Giaour and Coleridge. Those two bits of evidence served to ignite a great quantity of material which had lain about in my mind for 20 years. There were no more secrets. All was plain as day.

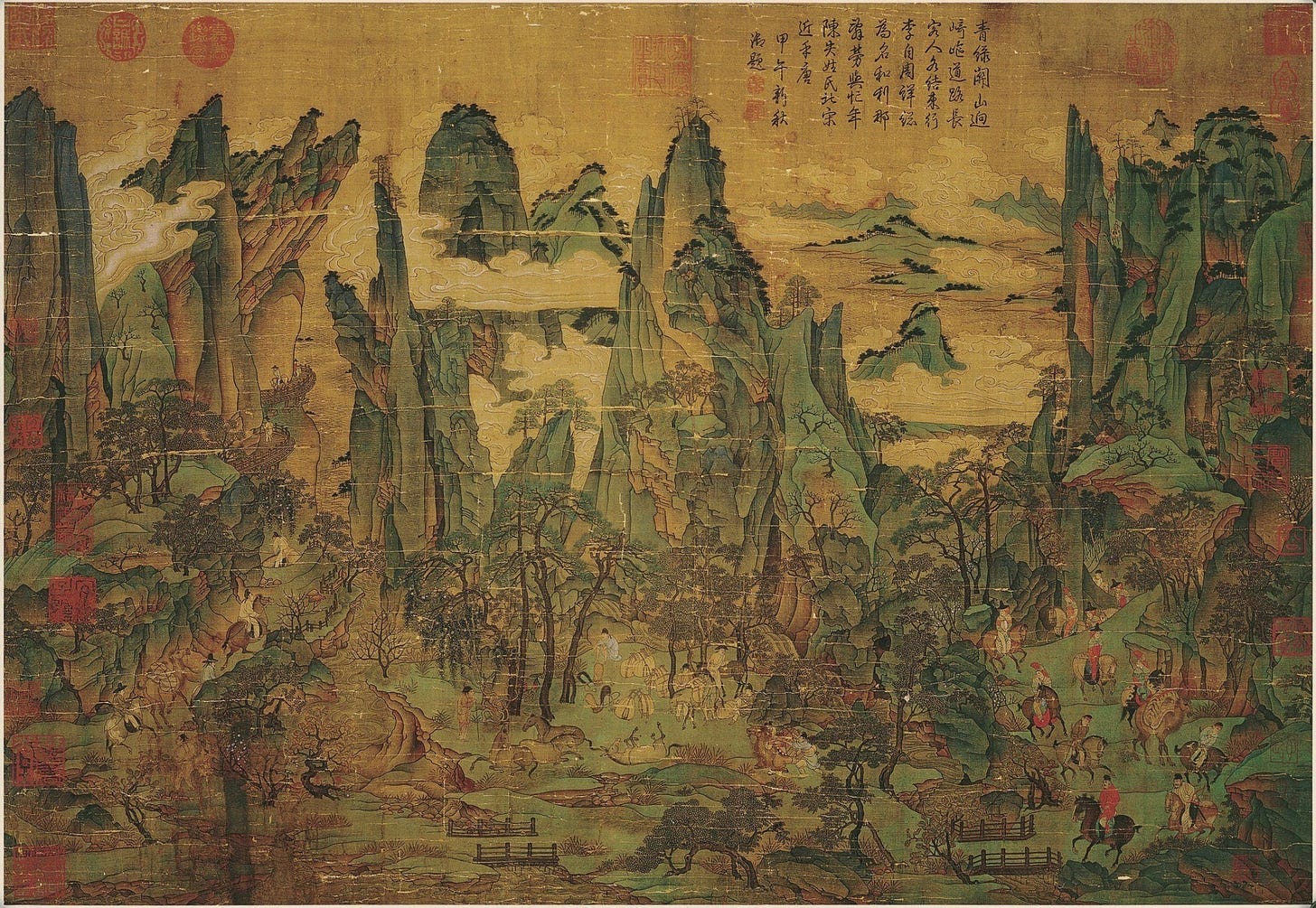

It is difficult to say why I find this set of Cantos so much more inter esting than last two week's, especially considering thatthe form has hardly changed. The content has undergone a radical metempsychosis however, being removed from the Italian-early-national-American panoramas of the great war to the long and storied history of imperial China as relayed by Pound's poetics. I have a semi-passing sense of the very broad strokes of Chinese history, the major Dynasties and thinkers, etc, so perhaps there was a little more for me to grab onto this time. In any case the most difficult thing about these . particular cantos is the very early twentieth century romanization of the Chinese words and names! Pound was deeply influenced by chinese poetry, which he translated in a deeply strange method which nonetheless delivered beautiful results-

suggested that I talk about Cathay if I found the next set of Cantos tiring, and I might next week if only because the actual part is so small!! He also became fascinated by Confucianism during this period. Hugh Kenner as ever offers an account of this in The Pound Era:The neo-Confucianism from which Pound trustingly received the Four Books was an aspect of Chu Hsi's syncretic mode of thought. That mode, nominally Confucian, had assimilated much coloration from I5 centuries of Taoism: from a tradition of thought that talks of harmony with the universe rather than of modes of government; that indeed tends toward anarchy in distrusting modes of government; that is quietist, not active, intuitive not intellective; that produces as model not the ruler but the hermit. So intrinsic are such impulses to the long story of China that we cannot sort out with any plausibility a Confucian orthodoxy which is radically something other. Tao, The Way, Confucius used the term repeatedly; we find it some 80 times in the Analects themselves.

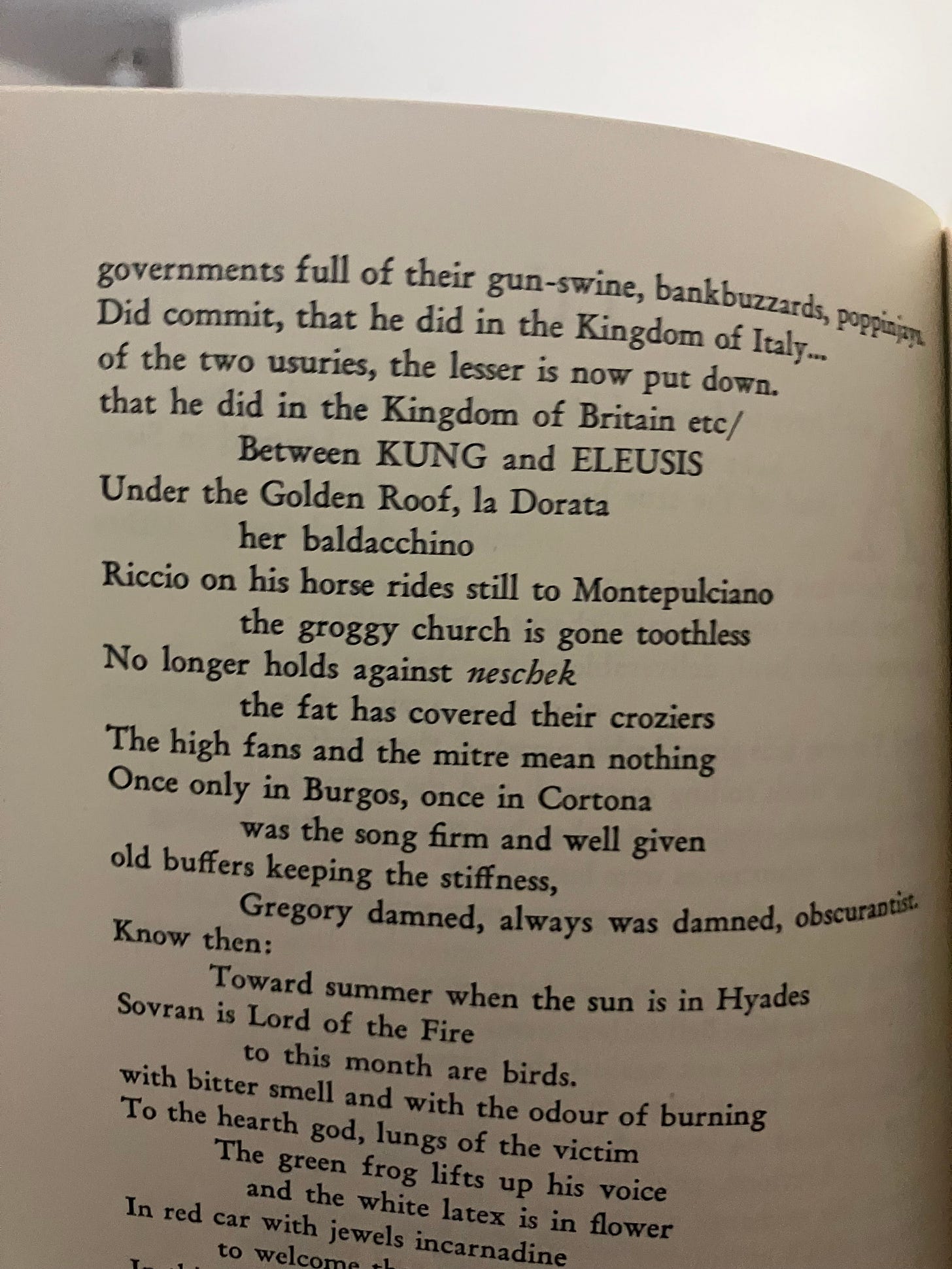

Last week I compared Pound to Thomas Pynchon, as a great American artist whose work dwells on conspiracy. Pound also shares with a few of the late twentieth century postmodernist novelists is a sense of an esoteric theology that favorably opposes a certain pagan or polytheist, pre-Christian or even pre-Jewish tradition to that which has governed the west (in the most broad sense of the west) for the last two millenia.1 This associates, especially in its liberal late twentieth century and early twenty-first forms, the antique polytheisms with pluralism and tolerance. One way to describe this conflict, in terms of the Ishmael Reed novel that Pynchon recommends in Gravity’s Rainbow, is to describe this as a conflict between the old gods and the Atonists, worshipers of the disc of the sun, of a fixed point in the sky. Later interpretations would add a gendered quality of this belief, and in one of those curious turnarounds that happens sometimes, will increasingly be associated with a "good politics" to oppose that voice which spoke out of the desert, out of the disk of the sun, which is praised in Akhenaten's Great Hymn and Psalm 104. Pound complicates this picture, as he does the one I was referring to in that first entry regarding the sort of Joycean-Mann-ish northern admiration of the Med which one comes over the course of Pound's century to associate increasingly with the sort of seemingly beneficent Liberalism of the postwar era. Pound was apparently quite unhappy with T.S. Eliot’s conversion to high-church Anglicanism, and there are multiple disparaging references to his onetime collaborator all over the earlier segments of the poem, which I dutifully forgot to mention.2 Oops. In any case, the politics of anti-Atonism are not as simple as they appeared to be in the 20th century.

In the second half of these Cantos the focus shifts from early modern China to the Unites States of America during the early national period, I can hear you groaning already, and muttering under your breath "is this going to be brought up every time??” but the way that Pound appreciates Confucius produces an emphasis, as Kenner reports, in a kind of statesmanship which I can't help but contrast to certain thinkers whom I have been reading of late. More on that tomorrow.

A man can grow committed to incompatible things. Pound's interest in the Fascism he idealized is continuous with his interest in the Chung Yung: in the belief that a ruler of sufficient sensibility, suficiently steady will, could catalyze a whole people's senso morale.

In this case the presidency of John Adams pere is the topic of this back half, what one of my reference books dubs the "Adams Cantos." It's been a minute since I studied the early national period, although I have a LOA volume of the first part of Henry [note: originally I confused him with his father Charles] Adams (direct relation) magisterial history of the Jefferson and Madison admins on my bookshelf at the moment. The main facts I remember from those studies are the existence of the naval quasi-war with revolutionary France which led to the establishment of a permanent US Navy, and extremely contentious domestic politics which would lead to the passage of laws related to censorship and seen as authoritarian by many contemporaries and successors of Adams, and led to a subsequent defeat by Thomas Jefferson in the election of 1800.3 What to make of this with regards to Pound I'm not quite sure. I can tell you as a lifelong Massachusetts resident the two Adams presidents are people you have a certain degree of ambient knowledge and respect for as local heroes, in somewhat the way the three Kennedy brothers are regarded, but at a much greater remove.4 There is a multitude once again of financial detail in this last section after a merciful reprieve from it in the Chinese Cantos, but it's not quite as jarring or overpowering as in some other points we've covered. There is a little bit of very ugly antisemitism at the beginning of the section, but there are mercifully few mentions beyond that

Stylistically this is the point at which Chinese characters begin to predominated in the way that I had come to expect from reading the Pisan Cantos earlier in the year, while there are slightly fewer digressions into other languages until the scene returns to the United States for the Adams material. Again, for reasons I am not fully able to elucidate, I found this section of the poem, very long though it is, a much easier read than either of the last two week's selections. At their best the Cantos accumulation of detail and disregard for anachronism, for time itself produces this almost-psychedelic affect in which all is one, 500bc is 1934 is 2025 is 1250AD is 200BC in the Xiongnu lands and 1917 in the trenches. This is one other reason that the poem reminds me of a certain kind of late 20th century work. Alan Moore and David Mitchell spring to mind, although both have very different sensibilities from Pound. If memory serves we are very near the inflection point where it all comes crashing down around him, where he will spend more than a decade living in one form of a cage or another after barely escaping being executed for treason, and if he never exactly repented, at least seemed to have some sense of knowledge that he had wasted his gifts on this thing, that what he had attempted was nothing else but vanity. I'm looking f forward to these next few entries, I should have plenty to say, and I'd love to hear your feedback as we go. Thanks!

I’m not sure that Thomas Pynchon partakes of this perspective, and indeed there’s an under-discussed vein of syncretic Catholicism running through American postmodernism, but this is absolutely something one picks up on if one reads late twentieth and early 20th century fictions, especially those influenced by the great midcentury masters.

I probably relate slightly more to Eliot’s version of modernism than I do Pound’s, and not just because I spent about half of my upbringing wishing I was British. The stating that one is instantiating genteel classicism, ancient grace, and then doing something extremely twentieth century I recognize as fitting some of my own aesthetic predilections, and Eliot at least knew not to write an 800 page poem about the decline of the sensibility or whatever. Though presumably in some swirling void there’s an 8-hour version of Cats.

It may be of some interest that one of said controversial laws is being used as the basis for some of the attempted purging of noncitizen residents deemed ideologically undesirable that’s taking place at the moment.

This is sort of neither here nor there to the Cantos and Pound, but I’ve always found it fascinating how that group of Kennedys managed to appeal to and invite identification from both the immigrant Catholic working classes-of Massachusetts and the nation at large-and the technocratic rising intelligentsia of the postwar period.

Eliot is one-L, always, and I think you mean HENRY Adams for the historian? The one who also wrote the novel Democracy and the rather imaginary history of Mont-St.-Michel called that? But perhaps I am wrong and there was a Charles one-d to differentiate from the delightful cartoonist Charles Addams who gave us the Addams family with his proto-Far Side weirdness.

I think - it may be wishful thinking -- that Pound did have SOME regret -- when you hear him read "pull down thy vanity, pull down" there is a weariness and sorrow that encompasses for me the knowledge that he first remade poetry with Yeats and Eliot, then wasted his life making it tiresome and dreary again. The last cantos (is it the Rock-Drill segment?) when he is very old, and I think beginning to drift into dementia, so writing short fragments more like George Oppen (read Oppen! Serously, read him!) than Basil Bunting (he's also good, for all his reputation is as a Pound-imitator), are suffused with melancholy and regret. I thought, when I read them.

Throughout my life, at low points and pompous ones, the voice of Pound rings in my head, "Pull down thy vanity/ Pull down" and centers me to the good and real work, and I go read Gary Snyder for another, much superior Pound follower. Also Paul Blackburn, who followed the troubadour thing deep and well.

Reading this while watching my garbage team play Aussie Rules Football in Melbourne. That’s my devotion to your devotion to the Cantos!