Better fifty years of Europe than a cycle of Cathay

Alfred Lord Tennyson, “Locksley Hall1

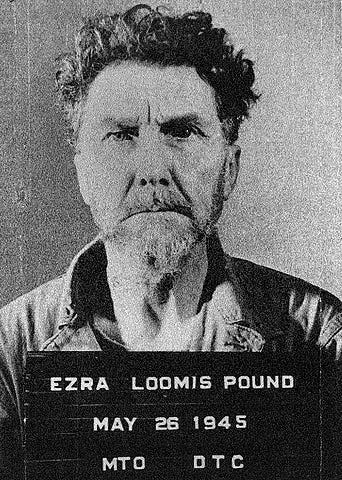

The two Cantos which make up today’s post cover barely twenty pages, both are written in Italian, and one is entirely untranslated. Both are quite fascist, probably the most explicitly so of those that we’ve read thus far. Written during the Second World War, a conflict in which Pound sided with the Italians and Germans over the United States and her allies, I’ve seen it argued that Canto LXIII has remained untranslated specifically due to the sympathetic light in which the axis are portrayed, and as will be discussed next week, Pound narrowly escaped execution after the war by somewhat dishonestly and disgracefully feigning insanity. As such I really don’t have that much to say about these poems this week. In order to avoid the question that was poised to me two weeks ago by a reader (is that it?) I thought it wise to consider a few of Pound’s pre-fascist works. First, a few thoughts about the overall nature of the poem and the style of the variety of modernism it partakes of. The Cantos are with something like Joyce's Finnegans Wake the logical endpoint of a certain style of literary modernism in which a hermeneutical devotion is demanded of the reader by the text and the author. The late twentieth century was besotted with this sort of thinking about interpretation, and I sometimes think some of the anti-intellectualism of the age we live in is downstream of that infatuation.

It sometimes seems that there are only two options for looking at the problem of modernist politics-the now deeply cliched and discredited "wow DH Lawrence was sooooo #problematic” and the now almost equally annoying "just shut up and read the great books you wokescold cucks" I persist in thinking that inasmuch as modernism has in a certain sense never ended, we should continue to wrestle with these angels, although it should be said that there is a correct and tasteless way to go about this. I make no claims to be succeding at either. Trilling's great essay "On the Teaching of Modern literature is a guiding light in this regard. I have quoted it before, and: very likely I will do so again.

I asked them to look into the Abyss, and, both dutifully and gladly, they have looked into the Abyss, and the Abyss has greeted them with the grave courtesy of all objects of serious study, saying: "Interesting, am I not? And exciting, if you consider how deep I am and what dread beasts lie at my bottom. Have it well in mind that a knowledge of me contributes materially to your being whole, or well-rounded, men.

Cathay belongs to Pound’s early period, although it was released in the midst of the First World War and some readers (Hugh Kenner for instance) have detected in it veiled commentary on that conflict. Pound's cycle of chinese translations, heavilly indebted to the late Ernest Fenelosa and of perhaps questionable value as translations considering his rather eccentric ideas about the Chinese language but nonetheless absolutely perfect poems in their own right, masterpeices of simplicity whihe still inspire more than a century later. These are poems that by comparison to the Cantos make one understand why Pound seemed to view his poetic life as something of a failure when all was said and done, and frankly considering the two one is often in agreement with him. “The River Merchant’s Wife, a Letter’ is a highlight, as is the whole collection really.

Instructive as well is Pound's other most famous long poem, “Hugh Selwyn Mauberly.” Somewhat comparable to T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land in theme, but much darker. Peculiarly given that it was Eliot who renounced his Americanness to become a British subject, there is still a sense in Eliot-assimilated to Christianity in the late work, latent in the description of the quotidian in The Waste Land-of some sort of otherworldly renewal, some sense in which this can and will be ok, life will go on amongst the ruins.2 Pound’s literary imagination after the war is far more apocalyptic. The angel must descend. Usury must be punished. The dead of the war must be avenged. Apollo in his glory must redeem the Aeon. The fascism of the middle cantos in some respects follows deterministically from “Mauberly” and yet they are not the same at all. There is a distinction between “Hugh Selwyn Mauberly” and the Cantos, one that somewhat mirrors that between Ulysses and the Wake. Both Mauberly and Joyce’s first epics are at bottom still readable. They have lovable characters, or don’t spend entire pages in Italian or Classical Chinese. One can read these works for pleasure, and not merely out of some misguided sense of duty or antiquarian drive to understand even what one lacks a utility for, what Blake Smith was the other day describing in a political context as “bug collecting.”

I am indeed prone to bug collecting of one variety or another, although in Pound’s case I would insist there is some utility to studying and trying to take in this most tormented and misguided of twentieth century American artists. It will become more interesting from here on out, I can promise this much. The last twenty years or so of Cantos are a fascinating ride, one in which Pound seemed to realize that he had squandered his gifts on politics, even as he never exactly seemed to repudiate the fascist sympathies or the antisemitism. The later Cantos become the meeting of the dead, and Pound in later life becomes like the ghost of Ajax, silent and full of rage and sadness, conscious of his failure. The revenge of the world upon him was severe indeed, and surpassed that of any other major modernist I can think of. Next week we will begin to examine them.

I largely owe this connection to a comment

left on ’s invisible college lecture on Tennyson last year

Re: "Cathay" in his (very good; would recommend) biography of Pound A. David Moody writes (after noting that when "Cathay" was published no one read it as commentary on WWI):

"But the beauty of it is that we are not getting the individual personality of Ezra Pound, nor indeed of Li Po. What we are given is impersonal in the sense that it belongs to no one person, and may be common to all. That is Pound's great technical achievement in 'Cathay,' to have found a voice that can speak quite naturally of a common humanity in war and love and other relations, and of himself not at all.

Eliot accurately observed that 'good translation like this is not merely translation, for the translator is giving the original through himself, and finding himself through the original.' But the poetic self found in 'Cathay' is far removed from the Pound of the aggressively insulting 'Lustra' and 'Xenia' and 'BLAST' poems. In those he is the irritated individual exulting over the common herd, all too full of himself and determined to speak his own mind. In 'Cathay,' in complete contrast, he is wholly absorbed in representing Rihaku, and yet in doing so he finds a voice which can speak with authority of timeless things exceeding the momentary rages and hates of Ezra Pound."

Iirc in the WRB I compared it to "Le tombeau de Couperin" once—neither need to explicitly condemn the war and its waste because their existence is the condemnation.