It is difficult not to contrast the beginning of the twenty-sixth subdivision of Hugh Kenner’s The Pound Era, “The Cage” with the manner in which the first, “Ghosts and Benedictions” opens on a vision of that image of gentility himself, the expatriated Henry James:

Toward the evening of a gone world, the light of its last summer pouring into a Chelsea street found and suffused the red waistcoat of Henry James, lord of decorum, en promenade, exposing his Boston niece to the tone of things.

Miss Peg in London, he had assured her mother, "with her admirable capacity to be interested in the near and the characteristic, whatever these may be," would have "lots of pleasant and informing experience and contact in spite of my inability to 'take her out'." By "out" he meant into the tabernacles of" society": his world of discourse teems with inverted commas, the words by which life was regulated having been long adrift, and referable only, with lifted ed'ebrows, to usage, his knowledge of her knowledge of his knowledge of what was done. The Chelsea street that afternoon however had stranger riches to offer than had" society." Movement, clatter of hooves, sputter of motors; light grazing housefronts, shadows moving; faces in a crowd, their apparition: two faces: Ezra Pound (quick jaunty rubicundity) with a lady. Eyes met; the couples halted; rituals were incumbent.

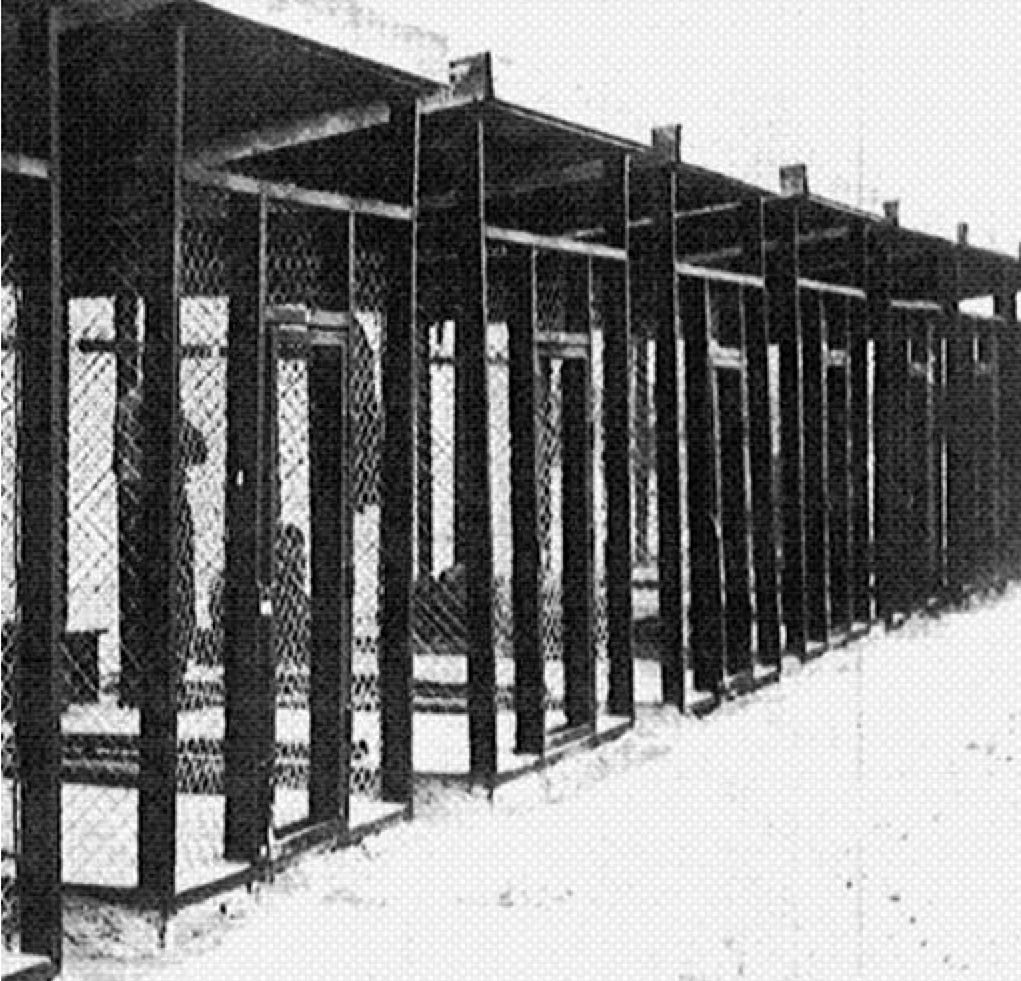

“Fifty years later, under an Italian sky” perhaps less than that, perhaps more, Ezra Pound was contained outdoors in a metal cage in a military camp, a traitor. His siding with Mussolini’s Italy which he had adopted as his home as surely as James did Großbritannian in the first war, although the corresponding renunciation was averted. He would escape the repercussions of this act, an act for which men less famous than Pound danced on the hangman’s noose and other such cliches, only by the somewhat dishonorable fiction of insanity. It would be more than ten years before he was freed from the last of these cages.

The men in the cages were incorrigibles. The man in the tenth cage of the ten was different: older than they, and bearded: (Dr.) Pound, E. L.: no rank, no serial number. He was in a cage because he was very dangerous, as witness the heavy air-strip that was welded over his galvanized mesh, with so many welds the acetylene torches blazed blue a full 36 hours. Some of the inner mesh was then cut off, for no clear reason unless 50-odd jagged spikes (what to do': but count them?) were an invitation (as he thought) to slash his wrists. He was sometimes tempted. A tough customer, clearly: he alone was never led outside for exercise. By day he walked in the cage, two paces, two paces, or slouched, or sat. By night a special reflector poured light on his cage alone, so he kept his head under the blanket. There were always two guards, with strict orders not to speak to him. Everyone, including the incorrigibles, had orders not to speak to him.

It may seem to some that I am being slightly unfair to Pound, over-emphasizing his political sins. I would defend myself by the argument that Pound’s political fixations came at the expense of the poetry. It should be remembered that Pound’s entire middle age was occupied by what we might call, taking a line from historians of late antiquity and the early modern period, the general crisis of the twentieth century. The world was rocked by an epidemic and an economic collapse of biblical proportions, bookended by two apocalyptic wars, the second truly global in scale. The English Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm influentially popularized the term the “short twentieth century” in his book The Age of Extremes, which somewhat conveys the meaning. Liberalism as a political system seemed totally discredited by the First World War, only to be improbably revived by the Second, then challenged by Marxism-Leninism, then triumphant, and now under threat again in our own time. Quoth Kenner once more:

The details are violent, the rhetoric disordered, the phraseology intemperate. The war was outrageous; in particular "For the United States to be making war on Italy and on Europe is just plain damn nonsense," and session after session he attempted in a few minutes to explain from halfway round the world to his countrymen how this nonsense had come about. Unlike the propagandist who says what he is told to, he was offering his own highly specialized account, so crammed with apparently unrelated allegations that some Italian officials are said to have wondered if he were transmitting code under their noses. The man who had had such trouble, and at leisure, in focusing the Monte Dei Paschi Canto clearly, was still less successful, under these conditions, in manifesting a semblance of calm. Exacerbations needled him. In particular, the principles of fiscal and civic order were difficult to talk about because they were so simple.

The Pisan Cantos are the part of the poem that indicates most clearly what was lost by Pound’s monomaniacal focus on politics and economics. It was art itself that Pound betrayed.

The Pisan Cantos are the closest thing to a must-read section of Pound’s epic poem; they are difficult and strange to be sure, but they are readable to one who is not a monomaniac, a certified Pound enthusiast, or constrained by a joke made a few months ago. It has thus tended to be the centerpiece of efforts to redeem the work of which it is a part, and Pound’s reputation more broadly.

This is not to say that reading the Pisan Cantos is an easy or lightly-undertaken thing, only that the experience is closer to Ulysses than Finnegans Wake. With some annotation and idea of what the overall schema of the Cantos consists of, the poem isn’t difficult to plow through in the same partly-comprehending manner as any other forebodingly opaque high modernist text.

From the earliest segments a focus on interior its and memory recurs after a lengthy digression of four hundred pages into heterodox economics, ancient Chinese and Italian history. This is not to imply that such things have disappeared, only that they are not the only things going on within the text. There is a vein of anti black racism running through several of these cantos, which is unsurprising for a white American of Pound’s generation, but not really worthy of any kind of extended discussion. In his last years Pound was famously reported to have described the antisemitism as “suburban,” questionable in that case, but the charge seems more accurate in this one.

An awareness and indeed a sadness at the passage of time which was lacking in the earlier cantos makes itself known here. The unity of time is still present as an element but Pound seems to grasp amidst the ruins of his and sixty million other lives that it might not be for him to hold, might not be any one’s. As the final Cantos will query, “can you enter the great acorn of light?” Whether Pound thinks he has will be one of the questions that we consider over the final few parts of this reading.

A question that haunts my perception not only of the Cantos but of Ezra Pound generally regards the relationship of history to extremism and the catastrophic vision of Pound’s mature work. If the naive genius of nineteenth century America, a nation in some ways culturally if not literally created ex nihilo, lay in the absence of history, of any vision of paradisiacal medieval or antique social order the restoration of which by technological-social visionaries mandates that billions must die, does not the recovery of history described by Kenner open for us a threatening vista? Is it possible that the world wars, rather than spoiling Renaissance II, were its logical conclusion? This is a little too deterministic for me in most moods, but I find it difficult to avoid. In any case, next week will bring discussion of Pound’s incarceration at St. Elizabeth’s, and in that spirit I close with Elizabeth Bishop’s great poem of that confinement, “Visits to St. Elizabeth’s.”

This is the soldier home from the war.

These are the years and the walls and the door

that shut on a boy that pats the floor

to see if the world is round or flat.

This is a Jew in a newspaper hat

that dances carefully down the ward,

walking the plank of a coffin board

with the crazy sailor

that shows his watch

that tells the time

of the wretched man

that lies in the house of Bedlam.

This is the house that Jack built....