One of the great frustrations of this project is that as I mentioned somewhere along the way, the Cantos are extremely uneven. A section of clear genius will be preceded and followed by material which seems obviously of lesser quality, even if it is not without its interest. The present group of cantos illustrates this quite well. After Pisa Pound was eventually in a somewhat dishonorable maneuver spared the hangman’s noose via the gambit of being deemed insane.1 He would spend the next decade and change incarcerated in St. Elizabeth’s, a mental institution outside of Washington DC. in 1949, after the release of the Pisan Cantos, the Library of Congress would award Pound the Bollingen prize for poetry in what was an ultimately unsuccessful effort by a number of his supporters in the literary establishment to secure his release. An enormous controversy ensued, and Pound remained incarcerated for another decade.2 W. H. Auden’s take on this incident was discussed in the last decade in the NYRB in light of various contemporary debates about the platforming of this or that problematic artist.

I get very exasperated with the people who argue that Pound should be acquitted or let down gently because he is a poet, which is obviously nonsense. The only claim for leniency can be exactly what it would be for any other criminal, on the grounds that he is mad, which is a matter for the court and the medical experts, not the public.

Auden wrote these words in the context of protesting the attempted deplatforming of Pound by his publisher, Random House. I should add that I find the deplatforming of artists-absent a very few special cases where even then I’m not totally sure- generally a sorry business. The basic assumption-that people will be inspired to do evil in some sort of mass way by this or that piece of art has always seemed questionable to me.3 Section: Rock Drill de Los Cantares LXXXV–XCV features as its predecessor did, some of the most beautiful passages in Pound’s poem, while also being frequently inscrutable, frustrating, or repulsive. A thread of Paradiso runs through the poem, one that will weave and remerge from time to time, but is particularly beautiful here.

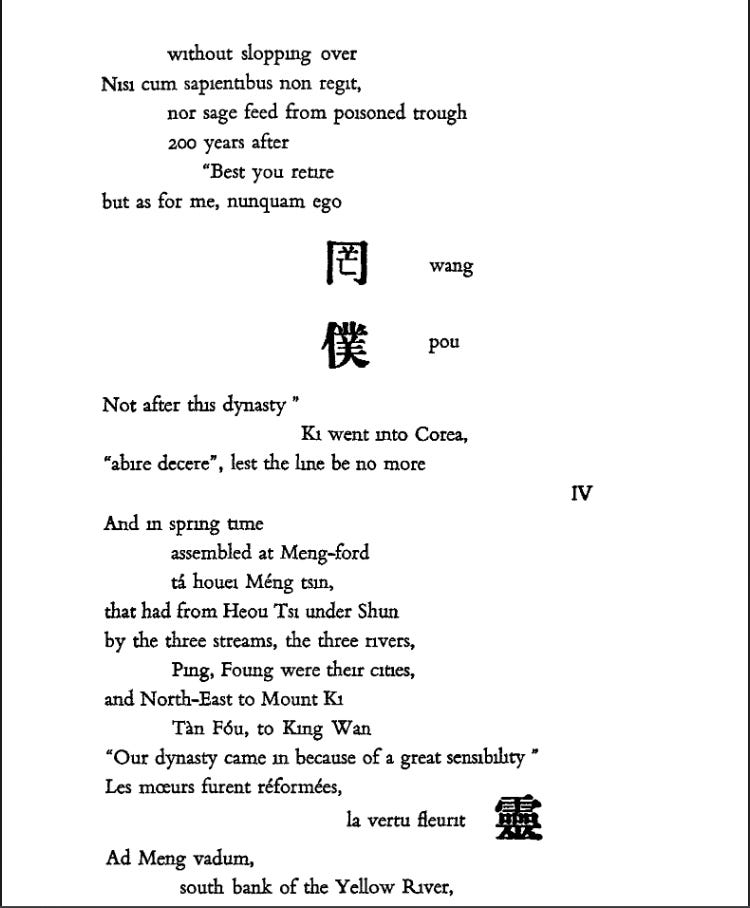

Good government as a theme runs through the work as a whole but is especially relevant here, where the opening cantos are I believe taken directly from a nineteenth century or earlier translation of certain neo-Confucian works. This preoccupation with the best regime and its relevance after the calamity of world war is probably the excuse I would trot out if I was ever challenged to defend the way people like Harry Jaffa have periodically invaded these digital pages supposedly dedicated to poetry. In a way I continue to wonder as I did last week, if the discovery of history by the nineteenth century empowers something menacing that simply did not exist in the American mind prior to the “Pound Era?” If knowledge of history, of the universal past of the human produces in turn a revulsion, a terror, a pseudo-nihilistic urge to escape from all that into a desperate attempt to evade the nothing, perhaps Pound’s phrase that the artist is the antennae of the race takes on a new menace? After all in the early 20th century you had to leave America, in some sense one almost had to stop being an American, as Eliot and James did literally, and as Stein and Pound did spiritually, in order to acquire Kultur. What might it mean for all those centuries to be at the fingertips of absolutely anyone who wants to know and has access to the internet? Might the real closing of the American mind be its opening to the wider world of history at large?

The two sets of cantos which follow Pisa are interesting in that contra my statement that these are the beginning of the slow turn toward those words that give this project its name, that sense o The sadness of these Cantos is not the sadness of repentance, but rather that of the destruction of a world. History played a cruel trick on Ezra Pound, as it did on many born in the middle and later parts of the nineteenth century. An example that has been insisting itself to me recently would be that of Richard Strauss, the image of the man who wrote Ein Heldenleben descending the stairs to surrender to the American officer, the sadness of the Metamorphosen, of the total destruction of the world those generations knew and sought to build for themselves. Probably that civilization didn't deserve to continue, underpinned as it was by horror and global exploitation, but still that doesn’t erase the horror of its passing, or the wreckage, the ruins in which we in the west are still to a large extent navigating. My great-grandfather always ended his history classes on the first world war, or so his sons told me twenty years ago, and there is a sense in which a history or histories did end in those terrible four years.4

The tragedy of the Cantos, and of Pound’s later life more generally, is that in seeking to prevent another war, in attempting to understand what he deemed to have been the cause of the war, he made himself, gradually at first and now in these postwar cantos quite explicitly a ghost. An angry spirit ineffectually rattling the chains of a madhouse, deemed wretched even by those fellow craftspeople disposed to a certain guild-loyalty to him. This willed obscurity has remained down to this day. He is too major to write out of the histories, too influential and too talented to disappear, and yet too problematic, too tainted to be anything other than the grey and smudgy image of a peacocklike man lurking in the background of a picture of some unrelated literary spectacle.

He may well have been mentally unbalanced, but as I commented last time, there were multiple people executed at the end of the Second World War for less than what he did. Something in the way Pound’s special treatment was clearly the product of his poetic genius (however he may have misused it) sits uneasily with me.

Perhaps relevantly to

, I believe Norman Podhoretz makes reference to this incident in either Making It or one of his other memoirs. I don’t remember particularly the details at this point.I can never make up my mind whether this position of mine, which I hold somewhat instinctively-that something in art fails to complete the circle, doesn’t reach the sphere of the fixed stars or the mimesis for which it aims-is actually true or merely something that it is important that we believe to be true, if only to keep the heat off the backs of artists.

He was a WWI vet himself. I don’t know if he ever saw combat, but was one of the white officers in a black company engaged in exhuming war dead for shipment stateside, a task which sounds horrifying in its own right. Before the war he had been a statistician working for a meat packing company in the midwest, which is a little too on the nose if you ask me. Afterwards wound up teaching history at Boston Latin, had Leonard Bernstein in a class, or so the family lore goes.