Finally, we should see the splendid powers of great individuals who would have enriched whole world-epochs, but who, misled and brought error or passion, or compelled by necessity, squandered them uselessly on unworthy or unprofitable objects, or even dissipated them on play.

Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation 183.

The sand of the sea, the drops of rain,

and the days of eternity—who can count them?

The height of heaven, the breadth of the

earth,

the abyss, and wisdom—who can search

them out?

Wisdom was created before all things,

and prudent understanding from Eternity.

Sirach 1:2-4, RSV 2CE

“In my beginning is my end” wrote a poet in rural Großbrittanien with whom Pound once shared a relationship during those same war years when Pound was singing his song for Mussolini in Italia.1 The last Cantos too begin something like this, returning to the Odyssey, to that which was after so many years away, so many years at sea. Odysseus returns to Ithaca after twenty years away, but the world is different. His vitality is not that what saw him away for Troy, and the last cantos reveal this. They are short, and they probably lose something if you haven’t read the whole of what precedes them, but they are great work, what you must read if you are interested in Pound. They don’t entirely walk back The Cantos in their monstrous schematicity, but they are the work of a different man than the writer even of the last few sets of cantos

It has long been observed that part of why one reads “modernism's beached whales” is simply to be able to say that one has done it, to rock the fit that says "I read Finnegans Wake and all I got was this lousy T-shirt” as it were. Coming to the end of the Cantos is fraught with mixed emotions, contradictory impulses, and the like. I did not appreciate when first I wandered Borgeslike through these pages how very much the change of heart in this late work comes out of nowhere, how even in the two sections of Canto which precede these last works Pound was going on about good government and Usura, that this embrace of silence and regret is really quite sudden and somewhat jarring in the shape of the work when you sit down and read it as a whole over a series of nine or ten weeks.

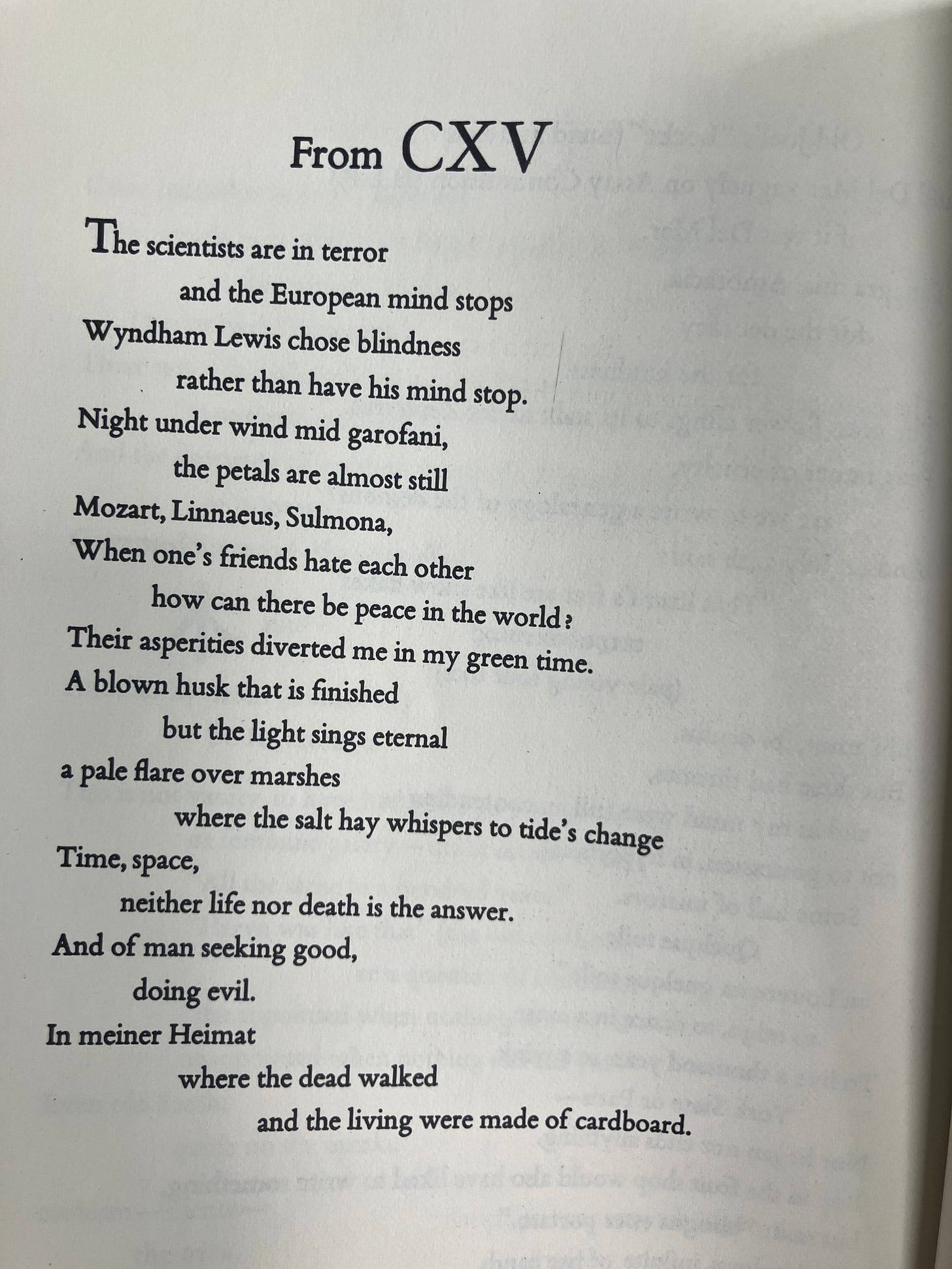

Subsequent to his release from St. Elizabeths in 1958, Pound retruned to Italy, where he infamously threw up the fascist salute on disembarking (it is fortunate for pound that his adopted homeland was Italy and not Germany.) In the years that followed the megalomania and the bravado, the pronouncements and unrepentant communications with neo-nazis that occurred during his time in the bughouse apparently ceased, and was replaced by a silence, indeed a seeming depression. In the last years Pound came to feel that his life had been a mistake, that his art had been in error. One finds some of this in these late Cantos. To quote for the last time Hugh Kenner:

Where had he gone wrong? What had been his root error? "That stupid, suburban anti-semitic prejudice"? He rummaged, sleepless, in a senescent cave. To seek the root error is an American habit. He had also sought it in history, and for a while equated the founding of the Bank of England with original sin; but that sin is not in time. To look back over one's path, and all its branches, and speculate on what might have been otherwise at each rejected path, that is an exhausting pastime. He should perhaps never have left America, or he should have returned there. He should not have buried himself in an Italian town, remote from the vectors of the world, and gone on excoriating American universities as though they were still indistinguishable from the Wabash of '907; and lost touch with the speech he loved and preserved and gradually parodied, always under the impression he was utilizing its immediacies.

That last Canto might be my favorite piece of work in the whole poem, possibly in Pound's whole oeuvre. This is of course personal. Reading Schopenhauer and Kojève as I have in the last year has clarified this for me enormously. The diagram of Kant as more or less opened circle, the skepticism that we have particularly reliable access to truth itself, all have had their part to play in showing me what is meant by all this. "who can enter the great acorn of light?" I'm not sure that anyone can.

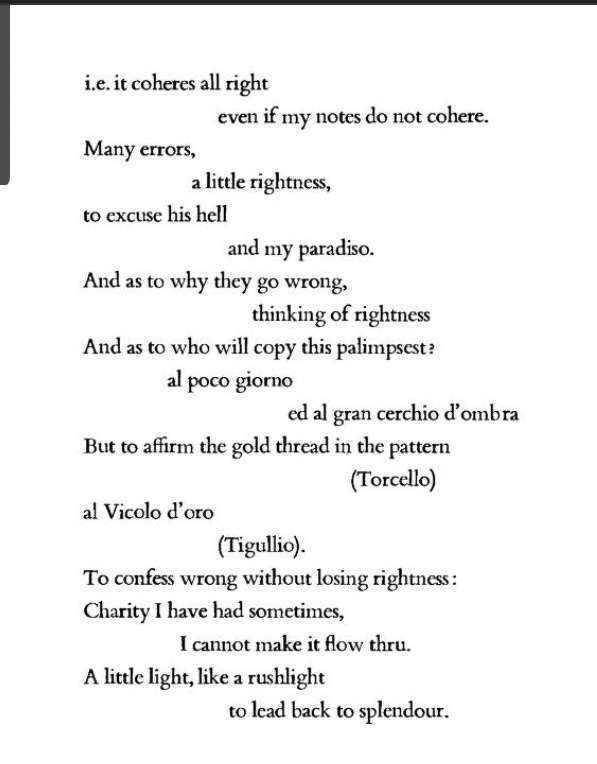

It is not for us to complete the circle. I would argue, although Pound would not and indeed does not, that is it not for our art to close the circle. Perhaps only a God or a great leap can do that. In these last Cantos something two faced issues without subterfuge or esotericism. Out of the same mouth two messages neither superior to the other. The most obvious is a walking back, an acknowledgement of Ezra Pound's failings as a poet and the way in which he seemed to betray his art in service of politics which failed to achieve their aim and indeed injured his craft and his reputation. Something like a renunciation of the sort of ideal of completion, of the perfect regime existing upon the face of the earth is implied in them, or so it seems to me. On the other hand, like that other great chameleon poet of the 20th century, Pound can’t give everything away: other interpretations lurk in these lines.

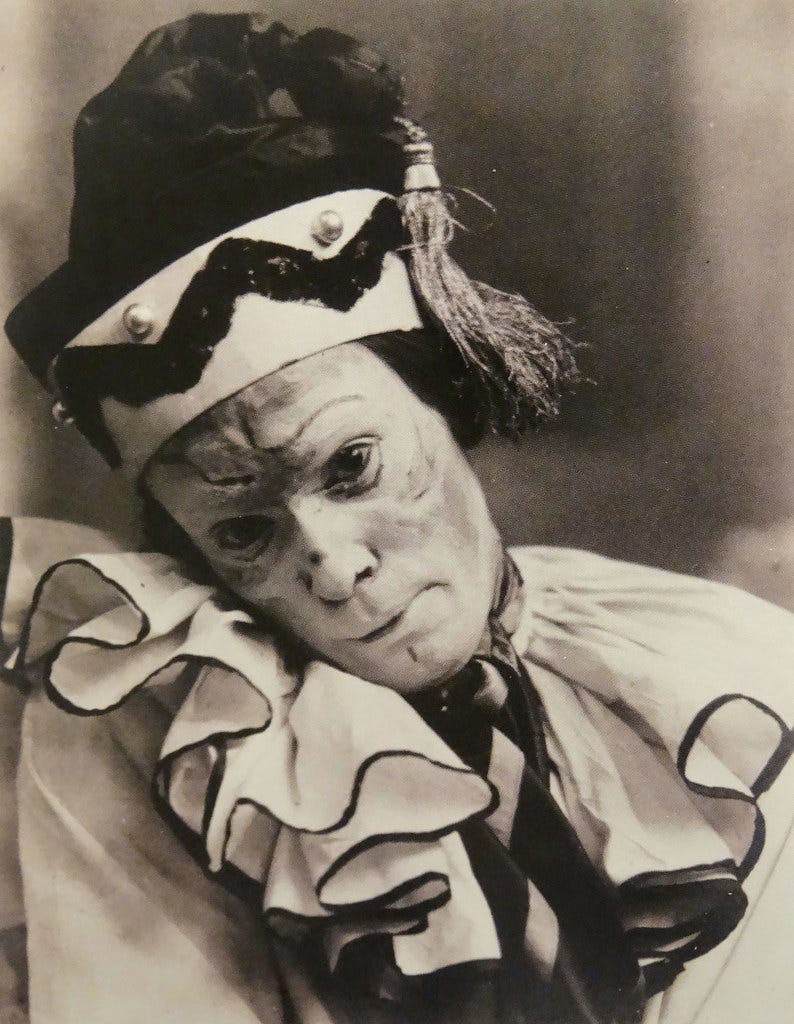

Igor Stravinsky’s great early ballet Petrushka narrates the romantic struggle and demise of the titular puppet, a Russian equivalent to Punch and Judy. In the course of a performance at shrovetide fair in Petrograd in 1830 his amorous advances are slighted by the Ballerina and he is ultimately killed by the Moor, who she prefers to him. At the close of the ballet, after the charlatan conducting the performance has reassured the audience that the puppet is merely that, Petrushka’s ghost looms over the top of the theater, threatening the charlatan, in some sense threatening us, we who have observed him for our amusement, before slumping over once more in a second death. The final Cantos have something of that flavor. At once renouncing the world and reasserting himself, is the end of the poem a chastened reflection on the inadequacy of Art and Politics, or is uncle Ezra coming back once again to proclaim himself an epochal genius?

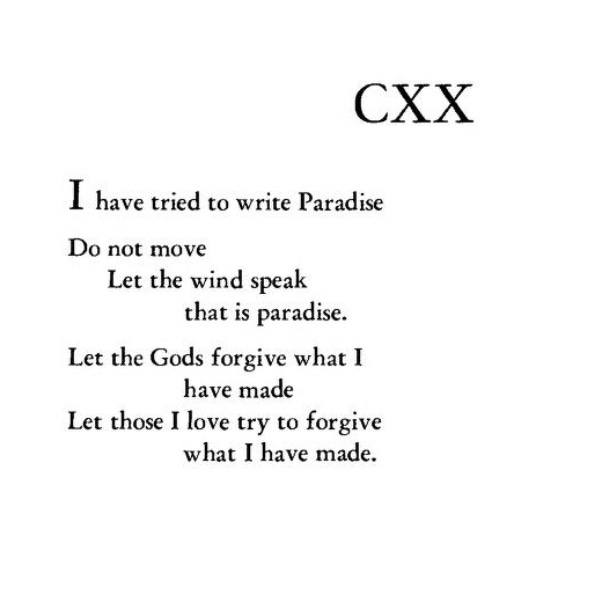

The great black book that sits on right wing shelves unread closes not with these cantos that I have discussed with you today, but with a few fragments from the 1940s and a few passages that were I believe intended as the original ending of the poem and then replaced. The first set is middling stuff, but Notes for Canto CXX has some real power. The dedications to Olga Rudge are also quite powerful.

Where Pound’s reputation will go is hard to discern. Kenner writes of him in the last pages of The Pound Era that “he is very likely, in ways controversy still hides, the contemporary of our grandchildren.” Hugh Kenner was of my grandparent’s generation, so the prediction hasn’t necessarily been fulfilled, but who can say what the future will bring. I imagine that if Pound does reclaim a more prominent place in American poetics, it will be primarily for the early and middle material, and not the Cantos. They simply demand too much of the reader, and are too devoted to a mostly forgotten crankery. There is tremendous beauty in these 800 pages, but the work of sifting through the wreckage to find it is enormous.

That Pound edited the truly vile antisemitic passages out of The Waste Land is one of the supreme literary ironies of the twentieth century.

Brilliant conclusion and congrats!! I feel as if I’ve just watched someone walk the Appalachian trail or pass the bar or something.

Lovely stuff. I know four of five bits of the Cantos really well ('What thou lov'st remains', 'With usura', 'Kung walked', and pretty much all of the lovely last ones. I suspect that will be more than enough - the pearls picked out of an edifice of conspiracism and obscurantism. Well done for battling thru!